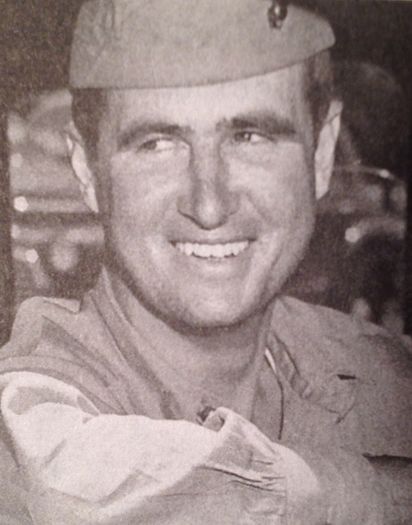

WILLIAM F. HARRIS, LTCOL, USMC

William Harris '39

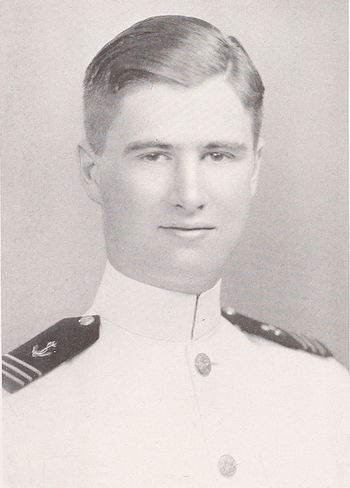

Lucky Bag

From the 1939 Lucky Bag:

WILLIAM FREDERICK HARRIS

Lexington, Kentucky

Bill, Happy

Bill, being more accustomed to tropical climes, was at first dismayed by Maryland's chilly nights, but soon he became so hardened that he even put the more northern men to shame with his contempt for the erratic weather of Annapolis. Many would like to discover, for frequent application, the secret of his resistance to cold. His ability to deliver long and complicated disquisitions in Dago has often filled several of the less adept of the first section with a sort of incredulous awe. Ask him sometime to tell you—in French—the story of the Kentucky Colonel. He prefers not to specialize in any one sport, but bangs away enthusiastically in many of them. Tennis in warm weather and handball in the winter months occupy most of his afternoons.

Star 4; M.P.O.

WILLIAM FREDERICK HARRIS

Lexington, Kentucky

Bill, Happy

Bill, being more accustomed to tropical climes, was at first dismayed by Maryland's chilly nights, but soon he became so hardened that he even put the more northern men to shame with his contempt for the erratic weather of Annapolis. Many would like to discover, for frequent application, the secret of his resistance to cold. His ability to deliver long and complicated disquisitions in Dago has often filled several of the less adept of the first section with a sort of incredulous awe. Ask him sometime to tell you—in French—the story of the Kentucky Colonel. He prefers not to specialize in any one sport, but bangs away enthusiastically in many of them. Tennis in warm weather and handball in the winter months occupy most of his afternoons.

Star 4; M.P.O.

Obituary

From Kentucky Marines:

William F. Harris was born March 6, 1918 at Lexington, Kentucky, to a family whose military heritage dates back to the Revolutionary War. His father, LtGen Field Harris, USMC, served as commanding general of the Marine Air Wing during the World War II invasion of Guadalcanal (1942) and later during the Korean War (1950). Following his graduation from the United States Naval Academy (1939), he was commissioned in the U.S. Marine Corps. While serving as an infantry officer in World War II, he was captured by the Japanese at Corregidor (May 1942), but subsequently escaped and after an 8 ½ hour swim across Manila Bay, he came ashore on the Japanese occupied Bataan Peninsula, where he joined up with Filipino guerrillas. When learning of the United States invasion of Guadalcanal, he set out to rejoin his Marine Corps unit; however, only reached as far as the Indonesian island of Morotai, where he was turned in to Japanese military officials and incarcerated. Upon learning that his father was a Marine Corps general, the Japanese moved him to the Prisoner of War Interrogation Center at Ofuna, Japan, where excessive torture of selected prisoners was a routine practice. Throughout his imprisonment, he plotted with others to escape; however, was unable to do so and when liberated at the end of World War II, was selected to stand on the deck of the USS Missouri, as Japan accepted terms of its surrender. Following the war, he returned home, fell in love with the daughter of a Navy captain, married and became the doting father of two little girls.

Harris remained in the Marine Corps following World War II, attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel, when he was called to command an infantry battalion at the outset of the Korean War. On December 7, 1950, with his decimated battalion serving as the rear guard for a Marine Corps convoy, a well entrenched numerically superior Chinese force launched a surprise ambush. Harris gathered his men under murderous fire and organized an attack straight at the Chinese position. Although taking heavy casualties, his battalion was able to hold the Chinese off long enough for the Marine Corps convoy to escape. Come dawn, Harris could not be found. After searching for him for hours, his men concluded that he must have been taken captive; however, at the conclusion of the Korean War, liberated American prisoners of war did not report seeing Harris in captivity. Harris was awarded the Navy Cross for his actions; however, General Clifton Cates, USMC, maintained the medal in his desk for the 32 year old Marine officer, hoping that he would someday return to personally receive it. Many years later, the family of William F. Harris received a box of bones apparently from North Korea, said to be his mortal remains. Due to incomplete reports, the family was never sure that the remains were those of William F. Harris; however, did arrange for them to be interred in a small country cemetery at the Pisgah Presbyterian Church at Versailles, Kentucky.

The saga of LtCol William F. Harris, USMC, is chronicled in the 2010 best selling book “Unbroken,” a World War II story of survival, resilience, and redemption, written by award winning author Laura Hillenbrand.

From Find A Grave:

Son of Lt. General Field Harris and Katherine Chinn, brother of Nancy E. Harris. He was a U. S. Naval Academy graduate Class of 1939. He was a veteran of WWII, taken prisoner on Corregidor, Philippine Islands. In Korea, he was the Commanding Officer of the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, Ist Marine Division. He was killed in action while fighting the enemy at the Chosin Reservoir, North Korea on December 6, 1950. He was mentioned in Edgar Whitcomb's "Escape from Corregidor" written in 1957.

Wartime Service

William is mentioned in FROM SHANGHAI TO CORREGIDOR: Marines in the Defense of the Philippines by J. Michael Miller.

From a blog post on Edgar Whitcomb and William Harris:

While working on Edgar D. Whitcomb‘s WWII memoir Escape from Corregidor I learned of a great American warrior, William (Bill) F. Harris. Detailed in Ed’s book is their escape from the Japanese by swimming across the Manila Bay from Corregidor to Bataan. Below is some short extracts from Escape From Corregidor detailing part of the escape:

Okay, it’s a deal, but I still think we should try to make it tonight. I just hate to think of spending another day in this place,” Bill argued.

The next day was May 22, 1942, and I was happier than I had been at any time since we reached Corregidor. While my fellow prisoners went about their daily routines, I was filled with excitement, for that was the day when Bill and I would make our escape from the island and from the prison camp. ……………….

It was about 8:30 p.m. when we lowered ourselves into the water to start swimming. There I stopped for a moment to kiss the old Rock good-by……………………..

For a long time it seemed that we were suspended there between the two shores, getting neither nearer to Bataan nor farther from Corregidor.

“What if it gets light and we’re still out here swimming?” and without waiting for an answer to my question, I went on, “We might possibly make it to shore without being seen, even in the daytime.”

How long those thoughts ran through my mind, I had no idea. It was like a dream, being somewhere and not being able to get away; but I was suddenly brought out of my bad dream when something hit my leg. Then it hit me again. Was it a shark? “Bill!” I screamed. “What is it?” he asked in alarm.

“Nothing,” I answered shortly. I could see no point in telling him and having him as frightened as I was at the moment. I imagined I saw fins cutting the water in circles about me, and at any moment I expected to be hit again. The next time I was hit, it was only a light touch.

Then Bill spoke up. “I think little fish are trying to eat me alive.” That was it! It was little fish. They were swimming along, trying to nibble at my arms and legs. After a while they left us, and all was calm again.

By this time it was clear that we were getting closer and closer to shore; then old Venus came peeking up over the eastern horizon like the red light that pops up on the instrument panel of a plane, saying, “Fuel pressure is getting low.” Old Venus seemed to be a warning light to us. We started swimming faster and faster, for it was beginning to get light.

Off to our right we were able to make out an object which we were unable to identify.

“Is that a ship?” I asked.

“Seems to be standing still, whatever it is.” We strained our eyes at the object until it took the form of a large seagoing barge.

“It’s not too far away,” I observed.

“No, I don’t think so. Maybe we had better go over and spend the day on her rather than try to make it to shore,” Bill suggested. We changed our course slightly to the right in order to bring ourselves closer to the barge. We were both very tired and eager to get some rest. But before we were halfway to the barge, we were able to make out the trees on the shoreline more distinctly, and we could see that it was only a short distance from us. Without a word we turned and headed for the shore, which offered much better security for us than the Japanese barge.

Some twenty feet before we reached the shore we came upon a lot of large rocks, and like two sea monsters emerging from the water, we struggled our way across the rocks and onto the shore. The place appeared to be completely deserted.

It was not until we were on solid ground that we realized how completely exhausted we were. In the cold gray dawn of Bataan I turned and had one last look across the channel, back to Corregidor. Then we both dropped exhausted into a clump of bushes.

When we awoke, the sun was low in the western sky. We were free!

Class of 1939 Marines at the Fall of Corregidor

At least seven Marines of the Class of 1939 were captured by the Japanese when Corregidor fell in May 1942; six of them perished in captivity. Four were awarded the Navy Cross for their heroism and distinguished service in six months of combat under arduous and increasingly desperate conditions. A fifth was awarded the Navy Cross for action in the Korean War.

Two men — William Hogaboom and Willard Holdredge — had extremely similar experiences, and are often mentioned together in after-action reports. Carter Simpson's was also similar; he also managed to keep an exceptionally interesting diary that survived the war. All three of these Marines were killed during or immediately after the attack on Oryoku Maru on December 14, 1945.

A fourth classmate, Ralph Mann, Jr., died in captivity in September 1942.

The final two, Hugh Tistadt, Jr. and John Fantone, survived the Oryoku Maru attack but perished in POW camps a few months later.

A seventh classmate, William Harris, was also captured, but escaped by swimming across Manila Bay from Corregidor to Bataan on May 22, 1942. He was later recaptured and tortured by the Japanese but survived the war to personally witness the Japanese surrender aboard USS Missouri. He was awarded the Navy Cross posthumously for his heroism in the Korean War.

Family

From Kentucky.com on December 23, 2014, by Jack Brammer:

VERSAILLES, KY — Katey Meares has a personal reason to see the movie Unbroken this Christmas season.

The epic movie, based on Laura Hillenbrand's 2010 best-selling book of the same name, describes the life of Olympic runner Louis "Louie" Zamperini and his harrowing ordeals in World War II.

One of Zamperini's colleagues in a hell-hole of a Japanese POW camp was Marine Lt. Col. William "Bill" F. Harris.

Meares calls Harris "Dad."

"I won't be able to go to the movies Christmas Day because I'll be too busy, but I want to go see it as soon as I can," she said on a recent night in her home in Versailles.

At least a half-dozen scrapbooks crammed with black-and-white photos and memories of her dad and other relatives were spread out on the floor of the front room.

"I've heard his character in the movie is not as big as it is in the book, but I'm still excited and proud about it," she said.

The movie, directed by Angelina Jolie, is expected to be one of the holiday season's blockbusters.

Hillenbrand, a Washington, D.C., writer whose first book was the acclaimed Seabiscuit, a non-fiction account in 2001 of the career of the great racehorse, corresponded with Meares about her father by email.

Meares' name and photo are in the book, which remains on the New York Times best-seller list.

In the book's epilogue, a photo shows Meares as an excited toddler on her father's back with her arms around his neck in Jamestown, R.I. He is a 32-year-old doting father.

The photo of the two, Meares said, was taken in 1950, a few months before her father disappeared as a soldier in the first winter month of the Korean War.

Photos of Meares' father and her other military ancestry adorn the walls of her house. Her family's military heritage dates to the Revolutionary War.

Her great-grandfather on her mother's side was John Archer Lejeune, a U.S. Marine Corps lieutenant general.

Lejeune, known as the "greatest of all leathernecks" and the "Marine's Marine," commanded the U.S. Army's 2nd Infantry Division during World War I. At the end of his nearly 40 years of military service, he was superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute.

Meares' paternal grandfather was Field Harris, a highly decorated lieutenant general in the Marines. He commanded the Marine aviation units during World War II and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing during the Korean conflict.

Born in September 1895 in Versailles and a 1917 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, the elder Harris saw his son, Bill, the night before he went missing in Korea.

In 1953, Field Harris bought the house in Versailles where his granddaughter Katey now lives. He died in December 1967. A historical marker about his life is near his grave at Pisgah Presbyterian Church in Woodford County.

Nearby is a moss-stained headstone that marks what are thought to be the remains of his son, William F. Harris. It gives a brief account of his military history, his birthdate and his date of death. The bottom line on the stone reads "Semper Fidelis," a Latin phrase for "Always Faithful," the Marine motto.

Meares is not certain whether the remains are those of her dad.

In the 1990s, she wrote U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell, seeking information about her father's identification.

She learned that the Navy thought that the remains were of Bill Harris. But only a DNA test could prove that, she said, and probably that effort would not be worth it. Regardless, she honors the grave site as that of her father.

Bill Harris was born on March 6, 1918, in the old Good Samaritan Hospital in downtown Lexington.

He lived all over the country as the child of a military leader. But he often returned to Kentucky to visit his grandmother on Big Sink Pike in Woodford County.

Following his graduation from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1939, Harris was commissioned in the Marines.

He was an infantry officer in World War II when he was captured by the Japanese at Corregidor in May 1942.

He escaped with another American, Edgar Whitcomb, who would later be governor of Indiana from 1969 to 1973. After an 8½ -hour swim across Manila Bay to the Japanese-occupied Bataan Peninsula, they joined up with Filipino guerillas. Whitcomb wrote about his and Harris' exploits in the 1958 book, Escape from Corregidor.

Harris later was recaptured and incarcerated, and he met up with Zamperini, the main character in Unbroken.

Throughout his imprisonment, Harris plotted with others to escape but never did.

At the end of the war, he was selected to stand on the deck of the USS Missouri as Japan accepted terms of surrender.

After the war, Harris returned to America, fell in love with Jeanne Lejeune Gleenon, married her in 1946 and had two daughters.

Katey Meares was his first child. The other daughter, Ellie, now lives in Colorado.

"Certainly I remember him," Meares said. "I was about 3½ . He was a wonderful father. I have nothing but happy memories of him. He was never cross with me even when I was naughty.

"He told me stories, read to me, played with me and carried me around. He was a very involved father, particularly for that era."

They were playing in the 1950 photo that appears in the best-selling book.

Meares remembers the day her mother got the telegram near Christmas Day in 1950 that said Harris was missing.

"I saw her crying," she said.

The little girl put her arms around her mother as she had done a few months before with her father.

After the Korean War, liberated prisoners of war said they never saw Harris in captivity. Many years later, Harris' family received a box of bones from North Korea that were said to be his remains. The remains were interred in the small country cemetery in Woodford County.

Katey Meares, a laboratory technician for the University of Kentucky's Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, said she never thought much about her dad until she turned 30.

"All these years since then, I've been very interested in him, who he was, what he did," she said.

When Unbroken came out, Meares participated in a book club discussion about it.

She also wrote to Zamperini and heard from him. Author Hillenbrand sent her an autographed copy of the book.

Meares' husband, Claude, died in 1988. Their son, Claude, is a former member of the Army Reserves. He now works for PNC in Lexington. Daughter Vicki Meares teaches school in Louisville, and another daughter, Nancy Snoke, is a software engineer in Nashville.

They will be in touch this Christmas season.

Perhaps, Meares said, some of them might go with her to the movies to see, as Hillenbrand calls it, "A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption."

They will be on the lookout for a person special to them.

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Lieutenant Colonel William Frederick Harris (MCSN: 0-5917), United States Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy of the United Nations while serving as Commanding Officer of the Third Battalion, Seventh Marines, FIRST Marine Division (Reinforced), in action against enemy aggressor forces in the Republic of Korea the early morning of 7 December 1950. Directing his Battalion in affording flank protection for the regimental vehicle train and the first echelon of the division trains proceeding from Hagaru-ri to Koto-ri, Lieutenant Colonel Harris, despite numerous casualties suffered in the bitterly fought advance, promptly went into action when a vastly outnumbering, deeply entrenched hostile force suddenly attacked at point-blank range from commanding ground during the hours of darkness. With his column disposed on open, frozen terrain and in danger of being cut off from the convoy as the enemy laid down enfilade fire from a strong roadblock, he organized a group of men and personally led them in a bold attack to neutralize the position with heavy losses to the enemy, thereby enabling the convoy to move through the blockade. Consistently exposing himself to devastating hostile grenade, rifle and automatic weapons fire throughout repeated determined attempts by the enemy to break through, Lieutenant Colonel Harris fought gallantly with his men, offering words of encouragement and directing their heroic efforts in driving off the fanatic attackers. Stout-hearted and indomitable despite tremendous losses in dead and wounded, Lieutenant Colonel Harris, by his inspiring leadership, daring combat tactics and valiant devotion to duty, contributed to the successful accomplishment of a vital mission and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

General Orders: Authority: Board of Awards: Serial 1089 (October 17, 1951)

Action Date: 7-Dec-50

Service: Marine Corps

Rank: Lieutenant Colonel

Company: Commanding Officer

Battalion: 3d Battalion

Regiment: 7th Marines

Division: 1st Marine Division (Rein.)

Photographs

Family

Andrew Harris '25 was William's uncle. He, too, was captured in the Philippines.

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together… or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

October 1939

LT Donald Lovelace '28 (Naval Aircraft Factory)

LTjg Edward Allen '31 (Naval Aircraft Factory)

June 1940

November 1940

April 1941

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.