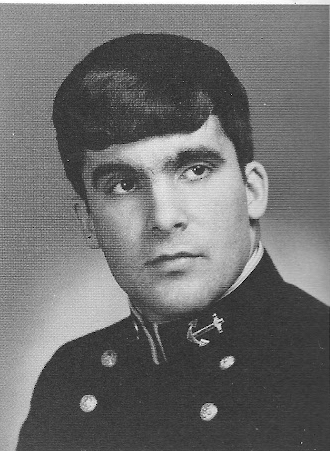

RICHARD C. HORMEL, LTJG, USN

Richard Hormel '71

Lucky Bag

From the 1971 Lucky Bag:

RICK HORMEL

Miami, Florida

When Rick came to Navy from Miami, Fla., via NAPS he brought with him many attributes foremost of which was his class. No matter what he engages in of a competitive spirit, save the game of chance he played and won with academics, Rick displays the gutsy class which led the 150 lb football team to a combined two-season record of 11-1 and which led him to the All-League team both seasons. No one can deny that Rick has led a colorful life at USNA since he has participated in such varied campaigns as the Battle of Trieste and a strange case of mistaken identity in D.C. one night. At any rate, in Rick the Naval Service receives a future flyer possessing a unique combination of cool class under pressure and great leadership ability.

RICK HORMEL

Miami, Florida

When Rick came to Navy from Miami, Fla., via NAPS he brought with him many attributes foremost of which was his class. No matter what he engages in of a competitive spirit, save the game of chance he played and won with academics, Rick displays the gutsy class which led the 150 lb football team to a combined two-season record of 11-1 and which led him to the All-League team both seasons. No one can deny that Rick has led a colorful life at USNA since he has participated in such varied campaigns as the Battle of Trieste and a strange case of mistaken identity in D.C. one night. At any rate, in Rick the Naval Service receives a future flyer possessing a unique combination of cool class under pressure and great leadership ability.

Loss

Richard was lost when his A-7E Corsair crashed while on a routine flight training mission from the Naval Air Station at Lemoore, California.

Shipmate

From the July-August 1975 issue of Shipmate:

Lt.(jg) Richard Charles Hormel USN died on 12 February 1975 in the crash of his A-7E Corsair near Lone Pine, California. He was attached to Attack Squadron 122 of the Naval Air Station, Lemoore, California, at the time.

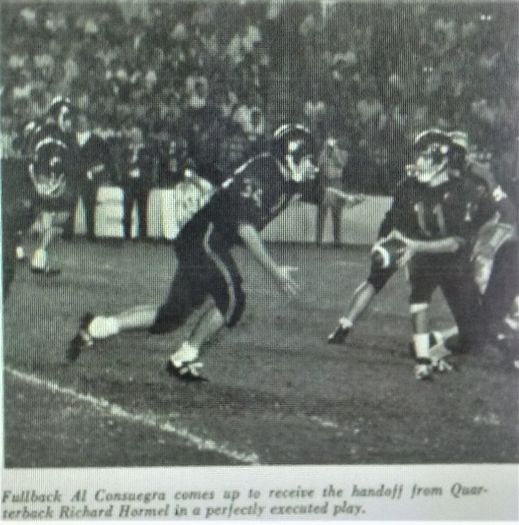

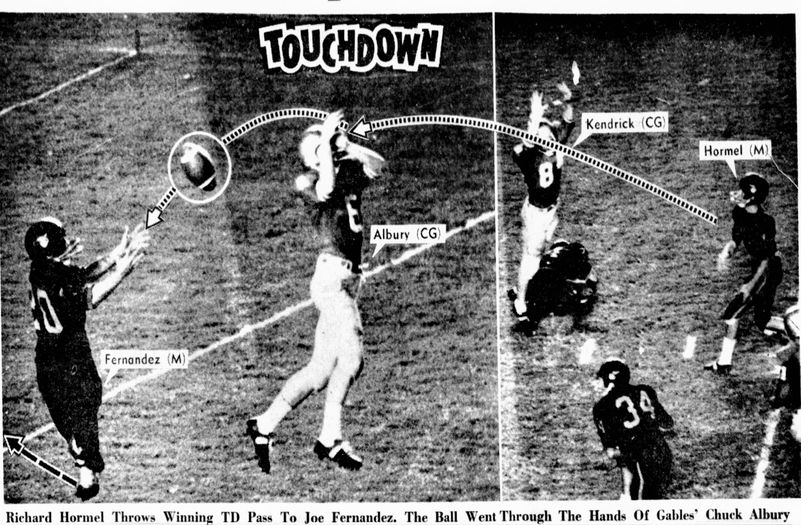

Lt.jg) Hormel entered the Naval Academy with an appointment from the naval reserve and was graduated with the Class of 1971. While at the Academy he was quarterback of the 150 pound football team which won two championships and was named All-Conference player these two years. He entered flight training after graduation and was designated a naval aviator in 1973.

Interment was in Flagler Memorial Cemetery, Miami, Florida, Lt.(jg) Michael S. Bluestein USN, his roommate at the Academy, escorting the body to the family plot.

Lt(jg) Hormel is survived by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Charles W. Hormel, of Chevy Chase MD.

Remembrances

From John Paulson '71 on August 21, 2022:

In the fast paced days of Plebe Summer 1967 and the year that followed, it was easy to identify many of those who were destined for early greatness, mainly football players. Rooming with a Plebe football player, lineman Wally Winslow, and being in the same Sixth Company as the Navy team's starting quarterback, Midshipman First Class John Cartwright, it was easy to identify the outstanding athletes in the Company. Rick Hormel was one high on the list, as a quarterback should be, even one weighing 150 pounds and throwing sidearm style. His undefeated Miami High School Team in 1965, also ranked as the top US high school team, and his quarterback efforts at the Naval Academy Prep School the next year (5-3-1) were well known among the plebes. His rise to greatness continued with exploits on the Plebe football team in 1967, since "Freshmen" were not allowed to play on college football or basketball varsity teams until 1972. However, the next year, 1968, as a Third Class Midshipman, he was competing for the varsity quarterbacking spot. He did get to play, sparingly, that year, completing four of eight pass attempts for 33 yards. His five runs when chased out of the pocket were non-gainers. Transitioning to the 150 pound football teams 1969 and 1970, resulted in back-to-back championships (11-1) in the Eastern Lightweight Football League, along with two All-conference QB selections.

During the relatively dismal days after the 1968 season, I got to know Rick much better. Through another Company member, Pat Alexander from Maryland, I became acquainted with a few local girls, especially "Bunny". She had a job in DC at the State Department and drove a new Pontiac Firebird. In early Spring, she wrote me a letter, saying she had two girlfriends she wanted to bring to Annapolis to meet midshipmen. I called her by pay phone immediately, and I invited them to a lacrosse match at the stadium on Saturday, lacrosse being a big sport in Maryland. Now, all I had to do was line-up some guys, with no definite time known. I got a lot of maybe's, including Rick.

Since Bunny didn't really know how long it would take her to get to the yard, back in the days prior to cell phones, I explained how they could reach us by going to the Main Office and having them relay a message to us via our company phone. Bunny knew the Main Office location in Bancroft Hall, up the main steps toward Memorial Hall after walking across Tecumseh Court.

My task became "lookout". I would observe T-Court after lunch from my room, overlooking the area from my top-floor window, and pass the word when they "appeared" and hopefully before they called. That way, the guys might have a chance to check them out before joining the walk to the stadium (no riding in cars back then). Without much waiting, three young ladies in the latest Spring attire entered T-court: Bunny, who was short (5' 2") with long brown hair, flanked by a tall "redhead" on her right and an even taller blond on her left. I went to tell Rick and the others, but they had noted the group, hoping it was the right one, and were already making preps to join the soiree. Unknown to me at the time, Bunny was also a singer in a local band and her two friends were models.

Anyhow, the word got out fast and I didn't have any trouble gathering a group of company mates to join us in the walk on a beautiful Spring day to the lacrosse match. However, I did purchase the tickets to the game for all three ladies. Midshipmen didn't have to pay. Everyone had a nice afternoon, breaking-up into three groups after the match. The girls would meet back at Bunny's car for a ride home later when our "Town Liberty" expired. In the weeks that followed, Bunny and her blond friend "Kathy" would visit me and Rick at the Academy. Temptations to go "Over The Wall" after liberty hours ended were frequent, but only for the brave. Longer term individual relationships were established, including the girls' attendance at the end-of-school-year events, dances, and ceremonies during the Class of 1969 Graduation's "June Week". I know that Rick's relationship with "Kathy" lasted much longer than mine, which ended after June Week 1969.

To quote 7th Company classmate, Mike Morrell: "Our friend Rick Hormel was quite a character. He was the best ladies' man I have ever met. He was not as good looking as some others, but he was persistent and daring, and not afraid of failure. When I first saw Tom Cruise going after Kelly McGillis in Top Gun, I immediately thought of Rick. He would have gotten the girl before Tom Cruise! At a party, I would stand to the side, and perhaps, ask one or two girls to dance. Rick would wade in immediately and ask every girl (if needed) to dance. He had no fear or shyness! When if first heard of his death, I was terribly sad, but I immediately assumed that Rick was pushing the envelope, causing him to do a maneuver from which he could not recover."

The LOG Article

From the June 4, 1971 issue of the midshipmen-published magazine The LOG:

There Will Be No Room For Mistakes…

I suppose I could be counted as one of those fortunate people who at one time or another during their lives had faced death, but through the good Lord's favor, somehow escaped to tell about it. I'm sure there are many people who have experienced the likelihood of death, but now, as one of the Grateful Society's newest members, I have often turned to the thought of the reasons for the sparing of my life. After much contemplation, perhaps the most important reason lies below.

It was a gray, lifeless day when I awoke to the usual clanging bell. "At least it's Friday," I thought to myself. My thoughts were way ahead of me already. I had looked forward to flying all day Friday since early in the week. I had no scheduled classes and my company officer proved kind enough to excuse me from meal formations so that I may be uninterrupted until the evening.

I jumped into my car after morning meal and hurried over to Friendship Airport, where my instructor awaited me. I was in the process of developing a large sense of self-pride in my ability as a pilot. I had recently been selected to go on for my Private's license after doing a good job on my preliminary exams and my minimum fifteen hours of flying. My first solo, as I recalled, had been my supreme experience. Nothing I had ever done before that day had ever equalled it. All I ever thought about any more was flying, and learning everything about an aircraft and its environment had become vitally important to me now I guess I fell in love with flying a childish notion, perhaps, but, nevertheless, real.

When I met my instructor, we proceeded to preflight the little Yankee, and before long, we were lifting off out of Friendship. We headed for Bay Bridge airport, where we decided to try a few takeoffs and landings. After awhile, we tackled tiny Cambridge airport, which proved to be quite a challenge.

Before long, my time was up. My instructor had to return to Friendship, but the plane was mine for the remainder of the day. I dropped him off and headed right back to Bay Bridge.

I practiced everything I though was possible in the Yankee. I knew my check ride was not far off, and that was the ride I wanted to be perfect. I must have tried every possible type of landing and takeoff, and after a while, I began to believe I could master them all.

But soon the repetition began to wear me down. I thought back to my instructor's conversation earlier in the day where we talked of the preparation for my first cross-country solo the following morning. I understood that I was ready for the major obstacle barring the path to my Private's license. I was ready now.

I looked at the time. It was 1500. I had five beautiful hours of daylight ... plenty of time to get in a cross country. My hands were way ahead of me. I watched them chart my course to Lynchburg, Virginia, a course I knew well now, since I had gone there on my dual cross-country with Mike, my instructor.

I called Washington Radio for my weather report. They replied with 5,000 ceiling, 6 mile visibility, and fog. "Fog," I thought to myself. It didn't sound good. I began to mull the situation over in my head. I thought it wise to go to an area I was already familiar with, I wanted everything right, I hated mistakes.

I finally decided I would go as far as I though was safely possible and, if it turned out to be a relatively long distance, I would claim that distance as my cross country.

I topped off at Bay Bridge and quickly got airborne. My first step was to tune my VOR to my first directional station at Brooke. I soon found that I could not receive Brooke. I thought immediately that my radio was out of order, but after checking over VOR stations, found my suspicions to be ill-based. I looked on my chart and decided to by VOR to Patuxent River, from which I would turn Westward toward Lynchburg.

After reaching Pax River, I found an excellent reception to Gordonsville VOR. The rest seemed to appear easy. Just by her and call Mike later on that night to tell him he didn't have to come to work the next day just to check out a plane for me. I knew he would be pleased with the motivation I tried hard at all times to express.

Visual reference proved my course true and everything seemed roses for awhile. But near Gordonsville I looked ahead and found several low hanging clouds. I estimated the ceiling there to be about 2,000 feet. Since my safety parameters dictated a minimum of 1,000 feet ceiling and 3 mile visibility, was not overly worried, but decided to call Washington Radio for another weather report. They replied Lynchburg weather (and I was very close to Lynchburg by now) to be 4,000 ceiling and 5 mile visibility. That weather report took with a grain of salt, but since my safety factor was still more than adequate, I decided to go on under the ominous cloud layer to the better weather at Lynchburg.

But the weather did not improve. I was forced lower by the steadily dropping ceiling. When I reached an altitude of 1300 feet, I decided to abort the original destination of Lynchburg. My decision was further supported by my varying VOR indications at my new altitude. I quickly switched to the VOR station back at Gordonsville, but found that I had no reception for my return trip home. A major decision was thrust upon me. I knew that the terrain behind me was flat and without distinguishing landmarks. My projected course included a river that flowed right into Lynchburg. Should my radio fail permanently, I felt assured by the fact that I could easily follow the river into the city, if I should be forced to do so.

Once again I called Washington Radio, but this time there was no response. I found myself alone for the first time.

I forged ahead, with the sole intention of finding the river that would lead me to my destination. After an agonizing period of time, I intercepted the river and quickly assumed a course directly over it. My ceiling now was 800 feet and still dropping I knew that I was entering a hilly area and felt that the safest place to fly was over the river.

Visibility by now was uncertain enough where I did not think it safe to take shortcuts over the endless windings of the river to conserve fuel. I was forced to follow strictly the course of the river. As I approached Lynchburg, cut my mixture as lean as possible to alleviate the growing problem of fuel consumption. My most immediate problem, however, was my ceiling. I was now flying at 600 feet and I knew that there wasn't any room for error anymore. There was time to pray... and I did, as I had done before only when I was in trouble, and now I thought lower of myself for my hypocrisy.

I knew that I soon had to deviate from the course of the river to reach Lynchburg Airport, but the elevation of the surrounding area (most of which was in the clouds by now) forced me to look for an alternative now. I knew that there was a small airport just a few miles from Lynchburg Airport, and I found that it was adjacent to a highway which led from the river. I decided that to land at the little airport would be my safest course of action and proceeded to follow the road away from the river.

I'm sure that many people on that road were convinced that was going to land on them, and apologized silently to them as I sought my tiny airfield.

Finally the numbers of the single strip shone clearly through the cockpit, but the sight I beheld then was almost beyond my belief -- the airstrip had been constructed right up the side of a hill. The normal procedure seemed to be to land up the hill, but to accomplish this, it was necessary to clear a ridge which by now went straight up into the clouds. Further investigation on my chart showed that there were high voltage power lines at the top of this ridge. I was quickly dissuaded from attempting this approach but decided to attempt a landing down the hill. I got no reception on my radio but warned them to stand clear of my awkward approach. I had no choice now.

I made a short field approach with full flaps, and I felt my tiny craft shudder as I approached and kept it at stall speed. The runway came fast but I dropped right on the numbers and jammed the controls forward to make her stick. I locked her hard working brakes with all my strength in the desperate hope I could stop her before she reached the downhill slope.

I felt her skid sideways as we went over the side of the hill and began picking up speed again. I quickly realized the attempt was now futile, and applied full power to get back off the side of the hill.

The only thing I wanted now was altitude, but I picked up too much in an effort to get away from the ridge which now faced me. I found myself in the clouds for the first time. It was a strange feeling… I had never been in a cloud before, I was taught to fear them. I felt as though I were motionless, that all movement had ceased to exist. But my sensation was brutally dispelled when I quickly stared ahead into the face of a mountain. I believed now that I was going to die. I can't remember if I experienced fear, I only knew that I was going into the side of that mountain.

I pulled back savagely at the controls. I could see thousands of trees speed by just under my wing, and I braced for the impact I knew would end my life.

But the moment never came. I had cleared the mountain.

I climbed. I knew that I needed any kind of communication, and the only thing I could offer my malfunctioning radio was altitude. But the climb was not easy. I began to suffer from vertigo. I found myself unable to maintain the attitude of my craft. Mike's words hit me hard. "Trust your instruments" -- listened to those words as I had listened to no others. I glued my eyes to my artificial horizon while I looked around outside the plane for any kind of reference.

I now called Lynchburg tower. Their response were the most beautiful words I had ever heard. "Lynchburg tower, over." The response was loud and clear.

I informed them of my now critical fuel shortage, my unknown position, faulty radio, and the rather obvious fact that I was a student pilot. After a few seconds, a calm, cool voice broke in. "We will direct you to Danville air port." They asked me pertinent in formation such as my fuel consumption rate and radio equipment available, while I gained altitude.

Shortly it was decided that I would not make it to Danville. My only chance was Lynchburg. A Piedmont pilot informed the tower that he wanted to bring me down on his wing. I flatly refused the offer as I felt sure I would only endanger his and his passengers' lives by attempting to find him in the cloud layer. To get over the top proved impossible. I was now at 9000 feet.

Radio informed me to reduce altitude to 3500 feet. I complied by cutting my engine to conserve what fuel I had left, and gliding down to my instructed altitude I returned power to my craft and recovered at 3,300. I knew that I was now lower than the surrounding mountains. I wanted to believe the voice which talked so calmly, I wanted to believe that he could talk me down… but I just wasn't sure.

I was now at 2000 feet. I followed perfectly every instruction given me, taking care to overcome the vertigo which troubled me greatly.

At 1700, I felt my fuel was in a critical state, and I wasn't sure that I would have more than one pass at the field. I informed Lynchburg tower of my state. This time he wisely did not answer. I knew that I was on an emergency approach. I would not endanger other craft in the area because of my own mistake in judgement. It somehow consoled me that least I was dealing with my own life, and no one else's.

Suddenly the radio crackled, "You should be directly over the field. Confirm if you see the runway lights." I looked over the side. My heart leaped as I saw the long rows of lights directly beneath me. That last approach was over quickly, and as my wheels touched down and I saw that I was going to live, I remembered the voice in the tower. I picked up my mike and said hoarsely, "You saved my life. Thank you."

And now the inevitable question. Who was at fault? What was the cause of this near-fatal accident? At the subsequent interrogation by all parties involved, it was decided by the final authority, the United States Naval Academy, that the reason was pilot error. The decision to return home should have been made sooner. Possible radio failure should have been taken into account, and that my instructor should have been notified. With all of these allegations, I concur.

I speak now to the men of the underclasses, the future aviators of the Navy and Marine Corps.

There comes a time in a man's life when he must choose something he will excel in. This he calls his profession. Flying is and shall always be my profession. I am fortunate to be alive today. From my experiences of a single day I have learned much. I have learned to respect an aircraft for what it is… not for what I think I can make it do. I have learned to respect weather… this is now a very deep respect. I have also learned to face death, and intense pressure, and there will come a time when every man will have to face this for himself… I pray that all of you will be ready.

Learn from my mistakes. When we combat the enemy together, there will be no room for mistakes… he must make the mistakes. Don't sell yourself short by not knowing the situation at hand, be it the condition of your aircraft, or the weather conditions around you. Let's not die before we can fight.

Respectfully,

Rick C. Hormel

Naval Air Class of 71

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

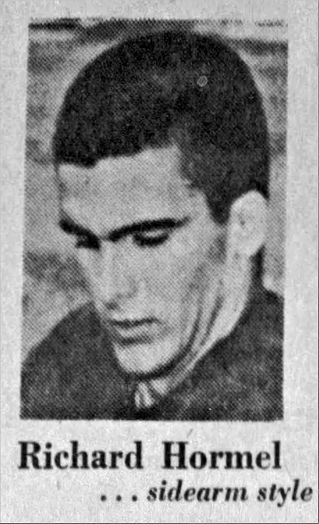

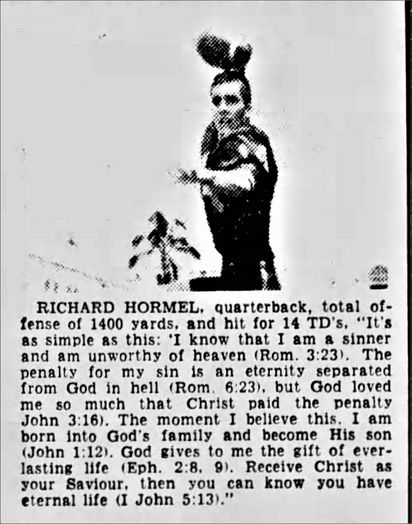

Richard was awarded Miami’s Prep Player of the Week on December 12, 1965. The next day's Miami Herald:

The 150-pound senior, overshadowed early season basketball efforts with his four touchdown passes in the Stingarees’ 44-12 state championship victory over Melbourne. Hormel also scored once on a three-yard run.

The game capped a surprising season for Hormel, who changed the recent image of Miami High quarterbacks with his passing proficiency. Hormel’s 10-for-21 performance against Melbourne and 237 yards was his best passing total of the season. Over-all, he threw for 863 yards in the regular season and 260 in two playoff games while quarterbacking Miami High’s first perfect season (12-0) in 22 years and its first state title in a post-season playoff.

(The game was played in the Orange Bowl.)

In an earlier news article, his coach Bobby Carlton said, “Richard’s sidearm style is unorthodox, he seems to draw from the hip. But with him it comes naturally. We have been trying to teach him to step back and throw with a smooth motion. But now, two years and 11 games later, I’m beginning to think our coaching has nullified his natural talent.”

In April 1966, Richard participated in “Bundle Day” which collected clothing from high school students to be sent to needy Appalachian families as the main project of the Save the Children Federation. (see photos)

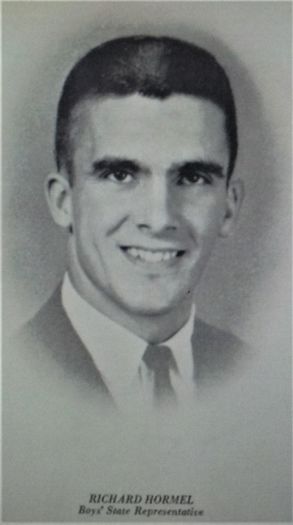

He graduated from Miami High School in 1966. H.R. Pres. 2, Student Council Rep. 3, 4; Interact 2, 3, Vice-Pres. 4; B-Squad Football 2, B-Squad Basketball 2, Varsity Basketball 3; Varsity Football 3, 4; Boy’s State Rep. 3; Student Council Cabinet 3, 4; Interclub Council 4; Hall of Fame 4.

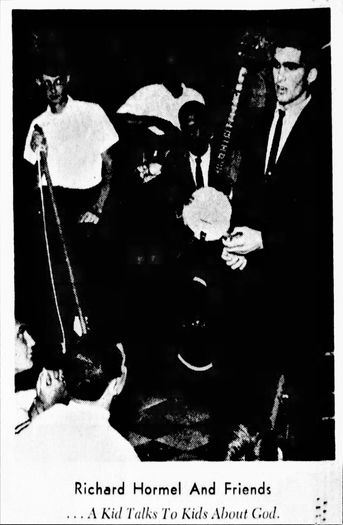

The Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida) on June 30, 1966, reported Richard witnessing to Jesus Christ before some 200 St. Petersburg youngsters at the Truth for Youth Ranch.

Richard is buried in Miami Memorial Park Cemetery.

Photographs

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.