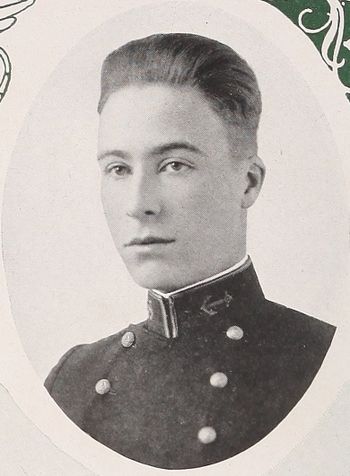

NORMAN S. IVES, CAPT, USN

Norman Ives '20

Lucky Bag

From the 1920 Lucky Bag:

Norman Seaton Ives

Washington, D.C.

"Ikey" "Poison"

BEHOLD the original two-gun man. The man who can draw, empty, load, empty, and return in two seconds. Fact.

And he has so darned many accomplishments we haven't the space to mention them all.

He can address the half-witted Midshipman with the same fecundity of phrase and the same benignity of expression that he utilizes against the ravishes of the fateful D. O.

He can crack a joke and be the only one to see the point.

He can take a cylindrical piece of lifeless paper and tobacco, caress it fondly, smile at it, light it warily, and forsooth—it becomes a thing of rare beauty, which exudes rings, S.'s, and stars at the capricious will of our "Ike."

He can enjoy a cruise on the Rhode Island as if it were a battle ship and wear Jackson's last suit of whites faultlessly at Saturday's inspection.

He can pitch a stellar brand of baseball and can be as happily indifferent to noxious regs as the blue-eared inhabitants of Central Nepal.

"Poison" and Red have led an ideal existence these three years. They fall out in the morning, beat each other senseless after dinner and fall asleep in each other's arms at night. And "Red" has never gotten a peek into one of those S. D. letters. Perhaps we anticipate, but wasn't he pricing miniatures the other day.

"Put 'em up, quick—draw and be quick."

"Say, going to Newport News?"

Honors: Buzzard.

The Class of 1920 was graduated in June 1919 due to World War I. The entirety of 2nd class (junior) year was removed from the curriculum.

Norman Seaton Ives

Washington, D.C.

"Ikey" "Poison"

BEHOLD the original two-gun man. The man who can draw, empty, load, empty, and return in two seconds. Fact.

And he has so darned many accomplishments we haven't the space to mention them all.

He can address the half-witted Midshipman with the same fecundity of phrase and the same benignity of expression that he utilizes against the ravishes of the fateful D. O.

He can crack a joke and be the only one to see the point.

He can take a cylindrical piece of lifeless paper and tobacco, caress it fondly, smile at it, light it warily, and forsooth—it becomes a thing of rare beauty, which exudes rings, S.'s, and stars at the capricious will of our "Ike."

He can enjoy a cruise on the Rhode Island as if it were a battle ship and wear Jackson's last suit of whites faultlessly at Saturday's inspection.

He can pitch a stellar brand of baseball and can be as happily indifferent to noxious regs as the blue-eared inhabitants of Central Nepal.

"Poison" and Red have led an ideal existence these three years. They fall out in the morning, beat each other senseless after dinner and fall asleep in each other's arms at night. And "Red" has never gotten a peek into one of those S. D. letters. Perhaps we anticipate, but wasn't he pricing miniatures the other day.

"Put 'em up, quick—draw and be quick."

"Say, going to Newport News?"

Honors: Buzzard.

The Class of 1920 was graduated in June 1919 due to World War I. The entirety of 2nd class (junior) year was removed from the curriculum.

Loss

Norman was killed in action on August 2, 1944 when the reconnaissance party he was leading was ambushed near Dol de Bretagne, France. He was the director of the port of Cherbourg, France.

From "The American Legion Magazine" June 1960 edition:

Ambush in Brittany

A story about an unorthodox and little-known World War II naval action in Europe.

By Bud Kane

"What the hell is the Navy doing here?" the armored division's commanding general yelled from his tank as it rumbled to a halt at a hastily improvised aid station in France during World War II.

The Navy lieutenant looked around at his temporarily nonnautical colleagues, incongruous in a setting normally expected only for ground combat troops. Some were being patched up by an Army surgeon; some were on stretchers waiting to be treated; and others were sprawled on the ground, unhurt but soaked with sweat and exhausted.

"I don't know," he retorted wearily. "But I wish I was back at sea." Then, suddenly noticing the two stars on the general's helmet, he looked sheepish for a second and added a belated "sir."

The colloquy, which took place near dusk on a hot August afternoon in 1944 in a Brittany orchard, capped the most unusual World War II Navy combat encounter in Europe. The bravery and heroism of the navymen involved has, until now, been mentioned only in a few lines by Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison in his history of the Navy in World War II.

On that afternoon of August 2, 1944, a Navy shore reconnaissance party of 97, accompanied by four war correspondents, became ground combat soldiers for several hours and battled the nazis for survival. Trapped in an ambush, the small naval party defended itself with only pistols and carbines against a task force of more than 500 heavily armed German paratroopers. The Germans were seeking to join forces with the major Wehrmacht thrust then hammering at the narrow Avranches corridor in an attempt to seal off American armor and infantry within the Normandy hedgerows.

Greatly outnumbered in men and firepower, the American sailors repulsed the heavy German attack for nearly three hours under a burning August sun at almost pointblank range. In the action, they captured two Germans and killed and wounded scores more before a task force of tanks and armored infantry from the 6th Armored Division rescued them from death or capture.

There might be no one alive today to chronicle this story were it not for the daring and quick thinking of a young Navy lieutenant (jg.) a a seaman, who together made a mad dash in a jeep under a fusillade of machine gun fire to bring help. Before help came, three officers and four enlisted men were killed.

Nine other officers and enlisted men were wounded and six men were separated from their unit for two days. Members of the French underground later guided the six back to American lines and safety.

The performance of the Navy party was sufficient to earn the Navy Cross for one officer, the Silver Star for a second, and the Bronze Star for two others.

At least half a dozen other officers and men deserved similar recognition for their heroism that day. But the action was so intense that only the correspondents, with no guns to fire, were in a position to note their bravery; so it went unrewarded. The few brief lines in Admiral Morison's history are the only recognition of their heroism.

For the four war correspondents, the episode began late that morning when the 6th Armored Division, to which they were temporarily attached, bivouacked for regrouping after the savage fighting encountered swinging around the Avranches corridor on the drive to Brest, the major port in Brittany.

The correspondents were Duke Shoop, of the Kansas City Star; Donald McKenzie, of the New York Daily News; Philip Grune, of the London Standard; and this writer, then a reporter-photographer for Star and Stripes.

While the armored division officers studied battle plans for their drive, the four correspondents and their GI driver, Private Harry Weilman of Chicago, left to check out rumors of the liberation of St. Malo, famed resort town on the north Brittany coast.

Major General Robert W. Grow, the division's able and daring commander, had just reconnoitered areas ahead of the bivouac, a few miles southeast of Dol de Bretagne, and told the newsmen not to venture more than a mile northwest unless they saw definite signs of American occupation of the area.

For the Navy party, the incident had its origin two days earlier when Captain Norman S. Ives, USN, commander of the port of Cherbourg, led a group of men from Cherbourg. They were to check the availability of ports on the north side of Brittany to land supplies badly needed by the invasion forces. Cherbourg harbor was still not cleared of mines, and supplies were still being landed on Omaha and Utah Beaches.

They cut through columns of foot soldiers slashing their way from the Periers-Lessay line through the Avranches corridor to open the door for General George Patton's Third Army tanks. At Coutances they were told that U.S. forces had captured St. Malo, but that town was actually still held by a rear-guard of German paratroopers who were then probing south and east to tie up with the nazi drive on Mortain, east of Avranches.

Guided by Lieutenant Colonel Kentan Carris, an Army officer assigned to them for liaison purposes, the Navy party of more than a score of jeeps, "recon" vehicles, and command cars swept past the corridor through side roads and drove up the Brittany peninsula to Pontorson.

Halting there to get their bearings, they moved northwest a few miles. There they met the four correspondents coming from a forked road nearly parallel to their own and leading toward Dol.

The correspondents, who had ridden for two miles without seeing any Signal Corps wires lining the roadside—the wire would have been an indication that American troops were in the area ahead—were just about to turn back when they saw the Navy party.

"Where are you headed?" one of the correspondents asked Captain Ives.

"We're moving into St. Malo," Ives replied, adding that they were planning to see if supplies could be landed there. Upon questioning, Ives said he had been assured that St. Malo was in American hands and looked to Colonel Carris for confirmation. Carris nodded agreement.

"We'll join you, then," said Duke Shoop. "There might be a good story in it."

The Navy party resumed its journey, with the four newsmen immediately behind Captain Ives and the rest of the convoy strung out over a quarter of a mile along the road.

The convoy had moved hardly more than a mile, however, when Captain Ives' driver called out: "There's a couple of Germans ahead."

He halted the lead jeep on a rise in the road, which was bordered on one side by a heavily wooded area and on the other by a grain field. Ives jumped out and called to the two Germans, who were only about 25 yards away, to come out of the brush behind which they were partly hidden. He covered them with his .45.

The Germans stood in the center of the road while Lieutenant (jg.) Adolph Heise and Boatswain's Mate 1st Class A. L. Haubert searched them for weapons.

Meanwhile, the newsmen had jumped from their vehicle and one of them whipped out his camera to get pictures of the Navy capturing German prisoners.

Lieutenant E. Milby Burton, the Navy party's intelligence officer, also took some pictures of the capture.

Ten seconds later the picture taking was interrupted by a hail of gunfire from approximately one hundred yards up the road. One sailor fell wounded and another staggered from a shot in his upper leg.

Recovering from the surprise, the Americans quickly split up and jumped into the ditches lining each side of the road. The two German prisoners followed suit as a fresh fusillade came from the woods not more than 50 yards up the road.

Lieutenant Commander C. U. Bishop, Jr. (now a Navy captain and with the Aroostook County, Maine, Civil Defense organization) took over the firing command of the Navy unit, and ordered Lieutenant Burton, Lieutenant Commander Arthur M. Hooper, Lieutenant Beekman Cannon and several sailors to deploy in the wooded area on the right.

Captain Ives held the center point, in the right ditch against a culvert. The four correspondents were immediately behind him, and a group of sailors were strung out along the ditch. The sailors were armed with carbines, but they had to expose themselves above the ditch to fire. They were additionally handicapped by the fact that Captain Ives was right in their line of fire.

Two sailors were told to guard the two German prisoners and prevent their signaling the enemy, and three others crawled back to help Lieutenant Ewald Pawsat, the Navy medical officer. "Doc" Pawsat, with his corpsman, Pharmacist's Mate William J. Newatk, was busy treating three injured men and readying bandages and sulfa powder for other possible casualties.

Commander Bishop took Lieutenant Commander Robert Marvin and Lieutenants Stephen S. Stone, Jr., and Randall Warden, and Ensign Harry Chamberlain into the grainfield on the left to form a firing unit against the Germans in the woods across the road.

Moving through the grainfield for a better vantage point, Bishop didn't realize that the movement of the grain gave them away until the Germans sent a still heavier concentration of rifle and machine gun fire at them.

Colonel Carris, in the left ditch, put his head up to warn Bishop of the giveaway signs and was immediately killed by gunfire.

Over in the right ditch, Captain Ives had run out of ammunition for his .45 and called to sailors behind him who were unable to use their carbines to pass them up to him. As Ives exhausted the clip in each carbine, a fresh weapon was handed to him, loaded by one of the correspondents immediately behind him.

Up to that point, no one knew the size of the enemy force or the extent of its firepower. This second question was answered with emphasis a few minutes later when heavy machine gun fire, accompanied by mortars, began to decimate the vehicles in the road. The first three were nearly demolished by mortar explosions. The rest were strafed and left standing with their tires cut into hanging rubber strips, and with water from their punctured radiators dripping onto the road surface.

Meanwhile, Burton, who with Hooper had taken position in the woods on the right, met a Breton farmer, Alexandre Souffre, lying in the woods. He had been returning to his hut nearby when the firing began and had seen the German force moving through the woods toward the road.

Souffre had fortunately escaped the Germans' notice and he told Burton that the enemy force was about 500 strong and that they were encircling the area, apparently preparing to close in later.

Burton called this news to Commander Hooper, nearby. He in turn crawled carefully back to the roadway edge to relay it to Ives.

"Captain Ives," he called from the edge of the wood. "Captain Ives."

The correspondents told him that Ives had been killed a few minutes before as he had moved to get a better line of fire against the Germans. However, they relayed his information across the road to Bishop, who sent back instructions for Hooper to withdraw his men and return to the ditches.

Hooper was killed a few minutes later, but not before he was able to instruct Burton to withdraw the men and stage a retreat.

Meanwhile, more than an hour had passed under the broiling hot sun. The Americans were under increasingly heavy fire, they were about to be encircled, and there was no relief in sight.

Commander Bishop yelled across the ditch for a volunteer to try to get help. Lieutenant Heise, who had moved into Ives' position, offered to get help. Climbing over one sailor after another, past where "Doe" Pawsat was treating wounded, he picked up Seaman 1st Class Joseph Zabadal and ordered him to follow.

Finally reaching the rear of the line, they both waited a few seconds for a lull in the firing and then, under renewed bursts of fire from the Germans, they made a dash for the last jeep in line. As they reached the jeep, more firing came from the grain field, spraying the road as they tried to turn the vehicle around.

Backing and turning frantically, as the men in the ditches yelled encouragement, they finally got the vehicle turned around and drove madly toward Pontorson.

They were hardly out of sight when the roar of an airplane sounded overhead and the beleaguered men yelled in relief as an American L-5 artillery observation plane flew overhead at about 2,000 feet. By that time nearly two hours had passed since the party had first been attacked.

The pilot, apparently noticing the empty vehicles in the road, banked his plane for a closer look at the convoy. Coming in from the same direction as before, he came down to about 800 feet and drew groans of dismay from the Americans as a German machine gun found its mark and strafed the plane and sent it into a spin.

The men watched in horror-stricken fascination as the pilot lost control and the plane slued northward over a clump of trees and fell out of sight more than a mile away.

The loss of the plane seemed to spur the men into renewed efforts to retreat to safety. Drenched with sweat, they crawled over one culvert after another to succeeding trenches, sliding wounded comrades across the culverts in pairs, under instructions of corpsman Newark and "Doc" Pawsat.

The medical officer frequently exposed himself to direct enemy fire as he and Newark treated Boatswain's Mate Joseph E. Dowling, Machinist's Mate Robert W. Gladwin, and Coxwain Ralph L. Meckfessel when the movement pulled off their bandages. Others helped Seaman Joseph La Flamme, Signalman Thomas Springer, and Lieutenant Ransford, a radio expert with the party, to safer positions in succeeding trenches.

Lieutenant Warden and Commander Marvin, both injured, wanted to remain to help in the fight, but Pawsat ordered them to move to the rear.

Ensign Chamberlain, a relative youngster, directed the withdrawal of a group of sailors while Bishop and Burton, who had come out of the wooded area with Cannon and his men to hold off the attackers, volunteered to remain as the last defenders.

Lying in the fields and unable to help were Robert F. Smith, Robert L. Brunn, William G. Reed, and Wilbur O'N. Elrod, enlisted men who had been killed by the devastating enemy fire.

Noise of the gunfire was suddenly broken by the muffled clanking and exhaust roars of tanks, and a shout went up from the men in the rear.

"They're tanks." they shouted. "They're our tanks."

And they were. Big, greenish monsters with the familiar white star on the front, they looked absolutely beautiful as they moved up, their big guns moving to and fro, sweeping the field. Behind them were members of C Company of the 25th Armored Engineer Battalion, a part of the 6th Armored Division. Lieutenant Heise had obtained help.

The tanks moved forward as their commanders yelled instructions from the turret tops to the navymen and correspondents within earshot, telling them to move to the rear under protection of their fire.

Bishop and Burton, their men moving to safety, asked for carbines and helmets from the tankers and engineers, and joined the soldiers to help rout their erstwhile attackers.

The tank guns and the concentrated fire of the engineers soon had the enemy moving back, but not before nearly a score of Germans were killed in the grainfield and in the woods.

An hour later the enemy was scattered and beaten. Back at an improvised aid station where the American dead had been brought, and where some of the wounded were still being treated, the 6th Armored Division's Commander, General Grow, brought his tank to a rumbling halt.

He greeted the correspondents familiarly and then, noting the Navy insignia on one of the officers, boomed out: "What the hell's the Navy doing here?"

Then it was that Burton, looking up from his position on the ground, dead and wounded lying nearby, blurted, "I don't know. But I wish I was back at sea."

And seeing the two stars on the general's helmet, he added sheepishly, "sir," and saluted.

Their heroism was best described in a communique by Commander Bishop—who received the Navy Cross for his own exploits—who wrote that "despite inexperience, their excellent discipline and stubborn resistance were in the highest tradition of the Navy."

Lieutenant Burton, during both the active fighting stage and later during the withdrawal, showed ground combat strategy to rival an experienced infantry officer. He was awarded the Silver Star for his superb performance.

Commander Hooper, among others, showed bravery of a high order and was decorated posthumously.

Lieutenants Cannon, Warden, Heise and Stone, Commander Marvin, Ensign Chamberlain, and others turned foot soldier for three hours showed enough courage and gallantry to merit high commendation from the Navy.

Lieutenant Pawsat, the medical officer, demonstrated exceptional disregard for his own safety under direct fire as he treated wounded men and arranged for their withdrawal. He was later awarded the Bronze Star and promoted, only partial recognition for his actions in combat.

Most of all, the enlisted men, too numerous to mention by name, deserve the highest praise.

Faced with a situation for which they had no real training, they nevertheless displayed bravery and rare presence of mind under fire and conducted themselves like experienced infantrymen. No higher praise could he offered.

The Germans?

Routed by tanks, they scattered in smaller groups and most were captured several days later by infantry units following the 6th Armored on its successful drive up to Brest.

Post-battle evaluations indicate that the 500 or more Germans, if successful in breaking through to Avranches, would not have altered materially the results of the vain Wehrmacht thrust to cut the vital corridor through which American troops flowed.

However, the defense put up by the intrepid Navy party helped prevent any change in the timetable of the American Army that, two days later, threw back the German drive from Mortain to the sea.

A week later the Americans killed and captured thousands of nazis at Falaise, opening the door to the Allied drive across France and eventual victory over Hitler's forces.

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

Born in Galesburg, Illinois, Norman graduated from Central High School in Washington, D. C.

Norman married Florence E. Nelson on December 27, 1919, in the Calvary Baptist Church in Washington, D. C. Their daughter Jane was born in Long Beach, California, on November 24, 1920. Son Norman, Jr. was born in 1923 in the Panama Canal Zone.

In April 1940, they lived in Honolulu. Florence had just returned to Honolulu the first week of December, 1941, after a few weeks visit to San Francisco. In September, daughter Jane worked at the Home Insurance Company in Honolulu and was president of Tau Omicron Phi, a sorority of officers’ daughters in the navy, army and marine corps. She married Lt. (jg) Sigmund Albert Bobczynski in April 1942.

Norman’s father Norman E. was federal pension and law examiner. His mother Fannie (Seaton) belonged to the Daughters of the American Revolution. His sister was Carrie Haroldine.

From the Evening Star, Washington, D. C., December 19, 1928:

The submarine S-4, which remained down by the stern in 55 feet of water when an attempt to raise her with new lifting hooks was made last night, was brought to the surface at 9:47 a.m. today. The craft had been deliberately sunk without a crew at 8:21 o’clock Monday morning. . . .

Lieut. Norman Ives, now in command of the S-4, stood with Lieut. Carlton Shugg, salvaging technician, who had his hands on valves controlling the flow of water out of the vessel below. “Give her a shot in the engine room,” Ives would command. “Give ‘em a little toot on the after end only,” Shugg ordered. Ives again speaking, “Are you still blowing the aft end of the pontoon?”

So it went for about four hours last night, but still the stern stayed down, and Lieut. Comdr. Palmer Dunbar ordered the submarine tender alongside to tie a line to the submersible to keep it from crashing against the Falcon.

The bow of the submarine was carried against the Falcon by a strong wind soon after the forward part of the vessel was raised, but no damage resulted.

The commander said the test of the lifting hooks was designed to determine their accessibility to divers, and the unexpected delay in the raising would point out new problems which would have to be solved before submarine rescue and salvaging methods were complete.

From the Evening Star on May 23, 1929:

The “lung,” famous submarine safety device, was tried out in the diving tank at the Washington Navy Yard this week at pressures corresponding to a depth of 302 feet, never before reached, and pronounced a success. The tests, conducted Monday and yesterday, were made on Lieut. Norman S. Ives, commanding officer of the reconditioned S-4 that was once the center of a great disaster, and Lieut. C. B. Momsen, co-inventor of the noted device, and Chief Torpedomen Edward Kalinowski and P. T. Hoy. Lieut. Ives has had limited experience in this particular phase of submarine work, while Lieut. Momsen is a pioneer in it.

Yesterday afternoon at 1:41 o’clock Lieuts. Ives and Momsen with Kalinowski and Joy entered the diving tank which contained about 6 feet of water. Pressure was built up to 133 pounds per square inch, corresponding to a depth of 302 feet, in 7 minutes. At 1:48 o’clock the release of the pressure was begun. “Lungs” charged with pure oxygen were used and Lieut. Ives had the new-style apparatus.

None of the men experienced ill effects from the experience, the Navy Department said today, in announcing the results of the tests.

In January 1930, the S-4 was towed to Key West for further experiments on the improved undersea mechanical lung and escape devices installed.

In August the S-4 was sunk to a depth of 45 feet in the Thames River Harbor, Connecticut. Lieut. Momsen and three newsreel men were aboard to film ten men leaving through an escape hatch of the S-4. However, after each man left, some water entered their compartment. By the time all men escaped, the water was waist-high. The apparatus to expel the water failed and a sudden lurch of the S-4 splashed water on the movie sound apparatus batteries causing chlorine gas fumes. Lieut. Momsen had extra “lungs” with him that they all put on. Norman commanded the S-4 to the surface, and the four men escaped unharmed. (Per the Evening Star, August 2, 1930.)

On January 1, 1932, Norman received a Central High School Alumni Association’s certificate of distinction for his hazardous S-4 experiments. J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Bureau of Investigation who broke up the Al Capone gang the year before, also received a certificate.

On February 11, 1932, Norman spoke at the weekly luncheon meeting of the Kiwanis Club in Washington, D. C. He traced the development of deep sea diving from as far back as the Roman Empire days when a leather helmet was used in diving. On March 16, he spoke to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

In September 1942, Norman flew with four bags from Foynes, Eire, to New York City on plane NC-41881 of the American Export Airlines, Inc.

In May 1945, nine naval officers of Submarine Squadron 50 were commended for offensive operations in European waters, including the sinking of a German submarine and an anti-submarine barge. Norman, who was the squadron’s commander, was awarded a posthumous letter of commendation.

His wife was listed as next of kin; he was also survived by his daughter, Jane, and son, Norman. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Photographs

Career

From the now-broken link http://www.fleetorganization.com/subcommandersclassyear.html:

- Captain USS Narwhal (SS-167) 25 May 1938 - 30 Apr 1941

- Commander Submarine Division Forty Three 1 Oct 1941 - 6 Feb 1942

- Chief of Staff Commander Submarines Atlantic Fleet 1942 - 31 Aug 1942

- Commander Submarine Squadron Fifty 3 Sep 1942 - 15 Jul 1943

- Commander Base Two Roseneath Scotland 20 Aug 1943 - 24 Nov 1943

- Duty With Commander US Naval Forces Europe/ Advanced Bases/Captured Ports 1943 - 1944

- Lieutenant Commander 1 Jan 1936

- Commander 1 July 1940

- Captain (T) 18 Jun 1942

USS S-4 (SS 109) had sunk following a collision in December 1927. The boat was raised and used as a testbed for submarine rescue devices and designs.

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant Norman Seaton Ives, United States Navy, for distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the submarine U.S.S. S-4 from 16 October 1928 to 1 August 1931, engaged in the hazardous duty of developing and perfecting the devices experimented with to make submarines safe for the operating personnel.

General Orders: Bureau of Navigation Bulletin 170 (January 9, 1972)

Service: Navy

Division: U.S.S. S-4

Legion of Merit

Unable to find a citation for the Legion of Merit he was awarded.

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together… or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

January 1920

January 1921

January 1922

May 1923

July 1923

September 1923

November 1923

January 1924

March 1924

May 1924

July 1924

September 1924

November 1924

January 1925

March 1925

May 1925

July 1925

October 1925

January 1926

October 1926

January 1927

April 1927

October 1927

January 1928

April 1928

July 1928

October 1928

January 1929

April 1929

July 1929

October 1929

January 1930

April 1930

October 1930

January 1931

April 1931

October 1931

January 1932

April 1932

LTjg Robley Clark '24 (Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.)

2LT Francis Williams '30 (Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.)

October 1932

LTjg Julian Morrison, Jr. '25 (Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.)

January 1933

LTjg Robley Clark '24 (Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.)

LTjg Fremont Wright '25 (Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.)

April 1933

LT William France '24 (Naval Gun Factory)

LTjg Fremont Wright '25 (Navy Yard, Washington, D.C.)

July 1933

October 1933

April 1934

July 1934

October 1934

January 1935

April 1935

October 1935

January 1936

LTjg Eugene Davis '27 (Observation Plane Squadron (VO) 4B)

April 1936

July 1936

January 1937

April 1937

September 1937

January 1938

July 1938

January 1939

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

Related Articles

Arthur Hooper '24 was also lost in this battle.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.