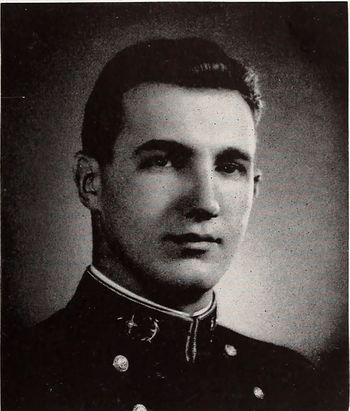

JOHN E. BARTOCCI, LCDR, USN

John Bartocci '57

Lucky Bag

From the 1957 Lucky Bag:

JOHN EUGENE BARTOCCI

Brooklyn, New York

A scholar, an athlete and a gentleman, John had long ago planned to make the Navy his career. He came from a family that has had the sea in its blood for over a century. After attending the Merchant Marine Academy for a year and a half, John decided to take a review course in plebe year. He packed his seabag, bid farewell to the merchant service and came to USNAY. During his stay here, there were times when he and the Academic Department didn't quite agree on certain points. Despite these few instances, he still managed to sport a couple of stars. Although women were his pitfall, they soon found out that the Navy came first with John.

He was also a member of the 2nd Company staff (fall).

JOHN EUGENE BARTOCCI

Brooklyn, New York

A scholar, an athlete and a gentleman, John had long ago planned to make the Navy his career. He came from a family that has had the sea in its blood for over a century. After attending the Merchant Marine Academy for a year and a half, John decided to take a review course in plebe year. He packed his seabag, bid farewell to the merchant service and came to USNAY. During his stay here, there were times when he and the Academic Department didn't quite agree on certain points. Despite these few instances, he still managed to sport a couple of stars. Although women were his pitfall, they soon found out that the Navy came first with John.

He was also a member of the 2nd Company staff (fall).

Obituary

From the December 1968 issue of Shipmate:

LCdr. John E . Bartocci, USN, died 31 Aug. in an accident during night carrier landing on USS Hancock in the Tonkin Gulf. He was a pilot attached to Fighter Squadron 24. Memorial services were held aboard the Hancock, and at the Miramar Naval Air Station Chapel in San Diego, when his father-in-law. Col, Cyrus J. Lemmon, USAF (Ret.), read a eulogy written by his wife. A memorial mass was also sung in St. Columba's Church.

LCdr. Bartocci was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1957. As a midshipman he was Second Company Officer, president of the French Club and played varsity baseball. After completing flight training at Kingsville, Tex., he served at the Ordnance and Repair School at Cherry Point, N. C, then was a pilot in VG-141, flying the F3H and the F-8 Crusader.

After completing the Naval Postgraduate School course in aeronautical engineering at Monterey, Calif,, he joined VG-24, deploying on his first combat cruise in January 1967 when he served as maintenance officer of the squadron. He participated in many heavy air strikes over North Vietnam, and had been awarded eight Air Medals, two Navy Commendation Medals, a Navy Unit Citation and the Vietnamese Campaign Medal.

He is survived by his widow Barbara of 3022 Kobe Drive, San Diego, Ca. 92123, two sons, John and Andres, and a daughter Allison; his parents, Mr. and Mrs. John V. Bartocci of 730 Montauk Ct., Brooklyn, N. Y . 11235, and a brother Douglas.

From Together We Served:

John Bartocci had a bright future when he graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1958. He was married the same year and began a family. His and Barbara's marriage was right out of a storybook. Barbara later said it was a "happy-ever-after dream."

John's Navy career moved the family from base to base until he was ultimately sent to Vietnam. In Vietnam, Bartocci flew the Vought F8 "Crusader". The Crusader was used exclusively by the Navy and Marine air wings and represented half or more of the carrier fighters in the Gulf of Tonkin during the first four years of the war. The aircraft was credited with nearly 53% of MiG kills in Vietnam.

LCDR John E. Bartocci perished while attempting to land aboard the USS Hancock (CVA-19) of the coast of Vietnam, 31 August 1968. Flying the F-8H (tail no. 147897), assigned to VF-24, his aircraft struck the aft ramp, broke into two pieces, and exploded. His body was never recovered.

Photographs

Remembrances

From the Springfield News-Leader on July 8, 2015, by Sony Hocklander:

Editor's Note: This story was originally published in February 2003.

Details of the summer evening that I learned my father would not return from war are as vivid to me as the moments each of my children were born.

It was dusk, August 31, 1968; I was 9 years old. We had returned to my grandparents' house from a vacation in Colorado. Coastal California felt cool because we were still dressed in shorts and sleeveless shirts to combat the Arizona heat while driving across the desert.

My grandfather, a retired Air Force colonel, guided the car into his Los Angeles driveway next to a strange beige vehicle parked there.

"I wonder whose car that is," he mused, turning off the engine.

My younger brothers and I, eager to unleash pent-up energy, raced around the grown-ups and into the house we loved like our own. There was the round white leather ottoman from Turkey, Granddaddy's favorite chair from Norway, the etched brass cocktail table from China. The Air Force had sent my grandparents all over the world, and it showed in every room.

I remember how suddenly everything seemed to slow, then stop. Through sliding glass doors that led to the pool out back, we watched two shadowed people push back from the patio table and stand up.

Navy Cmdr. Bob McLaughlin and his wife, Irene, two of my parents' best friends, had been waiting all day for our return.

My mother screamed. Then she whispered, "Oh, no."

The halfhearted joking among Navy pilots -- who never discussed death in serious tones -- slammed back into my mother's mind. She understood what was happening.

Bob, stationed shore side while my father's squadron was at sea, had been designated to bear the news should anything awful occur.

As my grandfather opened the back door, my grandmother began herding my younger brothers and me toward the back bedrooms. When I heard my mother cry out, I turned to look back.

"Not John," my mother sobbed as she sank into Bob's arms. "Not John. Not John."

Long night

The bedroom door quietly shut, and I was alone as my grandmother tended to my brothers.

My dad, Lt. Cmdr. John E. Bartocci, was stationed on an aircraft carrier in the China Sea. He flew F-8 Crusaders, the last of the single-seat jets, over Vietnam.

Already I missed his easy, boisterous laughter, his silly jokes -- "Everyone who loves Mommy, raise their left toe" -- and the feel of his large hands around mine as he showed me how to cast my line into a cool, green lake. I missed the clear spring evenings in San Diego we spent as a family on our patio, framed by palm trees, singing folk songs while Daddy played his guitar.

I heard muffled sounds from my grandparents' bedroom across the hall. My mother and Irene had gone in and closed the door.

"But John would not want to be dead," my 29-year-old mother told Irene over and over. "John would not want to be dead."

The grandfather clock bonged eight times, a comforting sound. My grandmother returned to help me get ready for bed. I was afraid of the answer to the question I had to ask, afraid to hear it spoken out loud, but I mustered the courage to speak.

"What happened to Daddy?"

"Wait until morning," my grandmother replied, her mouth pursed and grim.

Years later, my mother expresses regret that she didn't think about her children at that moment. The grief consumed her, squeezing everything out of her head, heart and body.

No one told us that night. And it was years before I shared with my mother what that long, anxious wait in the dark was like for me.

In my heart, I knew the truth. But lying in the bedroom where my uncle slept when he came home from college, I could not allow the word "dead" to form in my mind.

Maybe, I thought, Daddy was just hurt.

I tried to picture my father in the hospital with a broken leg. Would that cause my mother to wail?

Not John. Not John.

Then I imagined his head bandaged. Daddy unconscious in a hospital.

I dreamed up injury on top of injury. Each worse than the last. He was swathed in gauze from head to toe, fighting for his life.

But alive.

Maybe he was captured. A POW. I knew other Navy kids whose dads were captured or missing in action.

Not John. Not John.

"Daddy's dead," I whispered to no one as tears dripped silent salty trails to my ears.

Disaster on the deck

The next morning my mother brought us all into the room she usually shared with my father. Sitting on the edge of the double bed, she put Andy, 5, on her lap. Wrapping an arm around my brother John, 7, she hugged him tight to her side.

Her eyes were steady on mine as I curled up, hugging my knees, on a bench at the foot of the bed.

"Your daddy won't be coming home," she told us gently, her face still puffy from crying. "His plane crashed on the ship and he was killed."

It was years before I learned many of the details of my father's death. John Bartocci, 34, was the squadron maintenance officer, responsible for keeping jets in working order. When he flew fighter missions, his plane acted as a decoy, drawing fire so bombers could get a clear shot.

He once wrote to my mother that he learned to stop counting missiles after 12 or 13 had whizzed by. He was awarded 12 medals from his first tour of duty in 1967 in which he participated in heavy nonstop airstrikes over North Vietnam.

Daddy graduated from the Naval Academy in 1957, learned to fly in Pensacola, Fla., just before I was born and earned a graduate degree in aeronautical engineering at the U.S. Naval Post Graduate School.

The Navy was his life and he was the kind of man, my mother says, who was naturally at the center of things, who drew people around him like spokes in a wheel.

At the time of his death, Daddy was stationed at Miramar Naval Air Station in San Diego and was attached to the Fighter Squadron 24. By all accounts he was respected, beloved and considered a top talent.

What went wrong the night he died on the Hancock no one knows for sure. But several accounts tell it this way:

My father was on a nighttime reconnaissance mission. The weather had turned rough and on his return to the ship at 1:10 a.m. he was coming in low. The flight crew waved him off, and he tried to climb, pushing the plane up at full throttle.

But the jet crashed on the deck when its rear hook unexpectedly caught the arresting wire. The fuselage -- which carried my father -- exploded from the rear of the plane, skidding off the end of the deck into the Gulf of Tonkin.

Recovery efforts were unsuccessful; we never regained his body.

At school, I became "the girl whose dad died." Someone gave me a laminated copy of my father's obituary and for a long time other kids would stop talking when I came near, looking away awkwardly because they didn't know what to say.

My youngest brother, Andy, started holding conversations with an imaginary someone at the other end of a plastic toy telephone. Andy would tell my mother that he'd "talked to the ship and they said Daddy didn't die after all."

My middle brother became convinced that a submarine picked up our father under the sea. How did we know one didn't, he would insist. After all, we never saw his body.

Lasting loss

After the crash, I carried a distinct mental image that my life was split in two -- "Before Daddy died" and "After Daddy died." The image lasted long after we'd moved to the Midwest and into my 20s.

I also remember that we didn't just lose a father that day. For a while, we lost a mother, too.

Mom took us on lots of outings, to the zoo and the beach. But she was more like a chaperone than a parent, usually burying her mind in a book as we splashed in the ocean.

My brothers turned to me in small ways and I grew up fast. At night, I talked to Daddy in my head.

I missed the sheer silliness of my father, who enjoyed making his children laugh.

There was no more singing "Mississippi Mud" as we squished our bare toes into the smooth, cool mud of a bog near Mission Bay. No more winks when my mother got frustrated with the antics of wiggly young children who wouldn't stay in bed.

"Your father will have to give you 'the word,'" she'd warn. We'd giggle because we knew what that meant: Daddy would simply point to the bedrooms and announce with the false sternness of a commander, "The Wooord."

Mostly I remember camping and singing around the fire. My father, born and raised in Brooklyn, had learned to duck hunt at the same time he was learning to fly jets. By the time his kids came along, he was a devoted outdoorsman.

When I picture my father, I either see him in his orange flight suit or wearing his fishing vest and hat. He shared his passion for the outdoors with his children and by the time I was 8, he'd taught me to cast a line, catch a fish and clean it myself.

My father wrote letters almost daily from the carrier, and he often told mother how he ached to be with us again, to hold us in his arms.

"Received a wonderful photograph of you and the children," he told my mother in one note. "Barb, I cannot tell you not to worry or not to be afraid. All I can say is I hope it's in God's will that I return to you as scheduled."

A father remembered

As I got older, the late-night conversations with my father faded, pushed aside by the business of being a teenager, then an adult.

The overwhelming fog of grief eased for all of us, as it will for the children, wives and husbands in the Iraq war, for whom the hurt is now fresh.

I promise it gets better, but it never goes away.

Now my brother John plays our father's guitar for his children. His voice is poignantly similar, bringing tears to our eyes when he sings songs we shared with Daddy.

After college Andy almost followed Daddy into the Navy. He was driving from California to Pensacola -- where he'd been accepted into flight school -- when he finally realized in the silence of the car that he didn't really want to fly. He only wanted to feel closer to his father. He turned around and went home. Today, Andy works in the semi-conductor industry.

My brothers, mother and I are close, and we all live happy, fulfilled lives. My kids know "Grandpa John in heaven" from my stories. On taped recordings they've heard his clear tenor voice singing songs we loved as children. They've been to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, and used crayons to rub his name onto paper.

So in many ways, my father is still with us. But nothing ever erases the pain of losing someone you love in war.

From the Springfield News-Leader on July 11, 2015, by Sony Hocklander:

When I remember my father, a Navy officer and fighter pilot who served in the Vietnam War, I picture him wearing his orange flight suit, or his fishing vest and hat, or the casual weekend beach wear typical of 1960s San Diego — the last place I knew him.

He died in service to his country on Aug. 31, 1968, and is still listed as missing in action. He was 34.

When the Vietnam War began is a matter of historical debate for some, but the 50th anniversary of the conflict is being commemorated this year in Washington, D.C., and in communities — including Springfield — across the United States. Few would disagree the conflict left a bitter legacy. By the end, millions had served and sacrificed, and more than 58,000 Americans were killed.

Names of the fallen are inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in D.C.

They are also on the Vietnam Traveling Memorial Wall, a 60 percent scale replica on display Thursday through Sunday at the American Legion Vietnam War Memorial Post 639 in Springfield.

My father — John E. Bartocci — can be found on Panel 45 West, Row 12. Because his remains, along with the F-8 Crusader he flew, were lost in the Gulf of Tonkin and could not be recovered, the Wall is the one hallowed place his name lives on.

I have visited the D.C. memorial twice, most recently in early 2014. With its smooth, mirror-like black surface bearing thousands of names across three acres, the experience is powerful and moving. My first Wall encounter, though, was a traveling replica where I took my children when they were young. I appreciated the shared community experience to honor those who didn't come home, and I'm grateful to see the same opportunity in Springfield.

When I visit this time, I will look closely at many names and imagine the real people they represent: sons or daughters of people who loved them; perhaps someone's spouse — or someone's parent. I've been asked many times for my father's name by those traveling to our nation's capital. Knowing someone to look up on the Wall creates a more personal experience.

In the three years before his death, my father, a Naval Academy graduate, was stationed at Miramar Naval Air Station — made famous in the movie "Top Gun." Like other Navy families, we spent time on the base, sometimes dressed in our best for ceremonial occasions, or to watch the Blue Angels. Summer weekends were spent with other families at the Olympic-sized pool.

I remember short absences for naval training exercises. We said a big goodbye in 1967 for my father's first tour of duty to Vietnam. He returned with 12 medals for participating in heavy nonstop airstrikes over North Vietnam.

Our final goodbye was in June 1968, the month my parents celebrated 10 years of marriage. We didn't expect to see my father return until just before Christmas. But at summer's end, on the day my family returned home from a vacation road trip, two friends arrived to share the heartbreaking news.

I was 9; my little brothers 7 and 5. That day, my mother, 29, learned she was a widow.

I think for many of us, childhood memories run together like so much melted crayon — colorful pictures without much concept of time. But I still recall clearly every detail about the night I learned my father was dead. I can feel the sleepless long night, imagining the worst — hoping it wasn't true — before my puffy-faced mother delivered the news the next morning to her children. In 2003, I wrote about that night to share a child's perspective on what such loss means. It was part of a News-Leader special section publishing the first names and photos of Iraq War casualties. Twelve years later, I still hear from readers who remember my account or who have since discovered it online.

Enough time has passed that grief is more a memory. My family keeps my father close with stories, photos and recordings of his music. His guitar and flight jacket are cherished mementos.

When I visit the Vietnam Traveling Memorial Wall in Springfield, I will find my father's name and pay homage to him and all those who sacrificed their lives.

The Wall has thousands of stories. My father's is only one.

Sony Hocklander is the engagement editor at the Springfield News-Leader.

Both articles above contain a gallery of family pictures of John with his wife and children.

From Wall of Faces:

That night John died, I was a 23 year old LTJG in an A-4 Skyhawk 1/4 mile behind him and the next to land on Hancock after John cleared the landing area. The flight deck burst into flames and the debris slid up the deck and over the side. After wandering around for awhile trying to get hooked up with a tanker, I was finally vectored to the USS America where I landed with less than 500 lbs of fuel on board.

It was a hell of a night.

Because I was an LSO, I knew John well. Nice guy. I think of him often and visit him at our Wall South. JIM STEEL CDR USN (RET), 11/12/15

When I think of the Bartocci's I always remember Allison and I sitting on either side of Mr. Bartocci while he played his guitar and sang. When he came home from overseas one time he gave both of us a Japanese doll. It's been about 35 years and I still have that doll! ELLEN 'BOO' IOTT NUNLEY, 11/14/02

Family

In addition to his wife and three children, he was survived by (at least) his brother, Douglas.

From Heroes of the United States Naval Academy:

On August 31, 1968, at approximately 0133 hours, LCDR Bartocci was killed in action returning from a night reconnaissance mission. He was flying an F-8H. The weather had turned rough upon his return to the ship. He was coming in low. He was waved off, and he tried to climb, pushing the plane up at full throttle. But his jet crashed on the deck when its rear hook unexpectedly caught the arresting wire. The fuselage exploded from the rear of the plane, skidding off the end of the deck into the Gulf of Tonkin.

John Eugene Bartocci was born on February 19, 1934 in Brooklyn, New York to Mr. and Mrs. John V. Bartocci. He attended the United States Merchant Marine Academy before his nomination to the United States Naval Academy from New York. He was a member of the 2nd Company, the French Club and earned his Varsity N in Baseball. Midshipman Bartocci graduated 132 of 848 Midshipman on June 7, 1957.

In 1957, Ensign Bartocci was assigned under instruction at Naval Air Station, Pensacola Florida.

In 1958, Ensign Bartocci married Barbara Lemmon. Together they had a daughter Allison (Sony) and two sons, John and Andrew.

LTJG Bartocci completed flight training earning his wings at Naval Air Station Kingsville, Texas.

LTJG Bartocci was assigned to Ordnance and Repair School at Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, North Carolina.

LTJG Bartocci was assigned as pilot to Fighter Squadron 141 (VF-141), “Iron Angels”, flying the F3H Demon and then the F-8 Crusader. VF-141 was equipped with the F3H Demon.

From May 14 to December 1960 LTJG Bartocci and VF-141 were assigned to Carrier Air Group (CVG-14) for a deployment to the Western Pacific aboard aircraft carrier USS Oriskany (CV-34).

From November 9, 1961 to May 12, 1962, Lieutenant Bartocci and VF-141 deployed aboard aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-16) to the Western Pacific.

In 1966, Lieutenant Bartocci completed his Master’s Degree in Aeronautical Engineering at Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey California.

In January 1967, LCDR Bartocci was assigned as Maintenance Officer to Fighter Squadron 24 (VF-24) “Red Checkertails.”

In 1967, LCDR Bartocci and VF-24 deployed with Carrier Air Wing (CVW-21) aboard aircraft carrier USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31).

In June 1968, LCDR Bartocci and VF-24 deployed with Carrier Air Wing (CVW-21) aboard aircraft carrier USS Hancock (CVA-19) in the Tonkin Gulf.

On August 31, 1968, at approximately 0133 hours, LCDR Bartocci was killed in action returning from a night reconnaissance mission. He was flying an F-8H Crusader BuNo 147897. The weather had turned rough upon his return to the ship. He was coming in low. The flight crew waved him off, and he tried to climb, pushing the plane up at full throttle. But the jet crashed on the deck when its rear hook unexpectedly caught the arresting wire. The fuselage exploded from the rear of the plane, skidding off the end of the deck into the Gulf of Tonkin.

The destroyer USS Brinkley Bass (DD-887) conducted search and rescue efforts and recovered the pilot’s kneeboard, navigation bag, and a badly damage helmet. LCDR Bartocci’s remains were not found.

LCDR Bartocci personal decorations includes: Purple Heart Medal, Air Medal (6), Navy Commendation Medal (2) and Navy Unit Citation.

LCDR Bartocci is remembered by a memorial stone at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia, Section I. He is also remembered by a memorial stone at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, Point Loma, California.

LCDR Bartocci is remembered in Memorial Hall at the United States Naval Academy where his name is engraved under the “DONT GIVE UP THE SHIP” honoring those alumni killed in action.

LCDR Bartocci is remembered with a stadium chair named in his honor at Navy Marine Corps Stadium, Annapolis Maryland (Section 28, Row 10, Seat 19). “JOHN EUGENE BARTOCCI LIEUTENANT COMMANDER USN CLASS OF 1957 BY HIS CLASSMATES 28-10-19.”

LCDR Bartocci is remembered at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall, Panel W45, Line 12, Washington, DC.

Related Articles

Steven Kadas '57 was also a member of the 2nd Company Fall Leadership set.

Memorial Hall Error?

John is listed on the killed in action panel in the front of Memorial Hall. While not an obvious error, inclusion on the panel for crashes like this (incidental to combat flights) has been inconsistent across WWII, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.