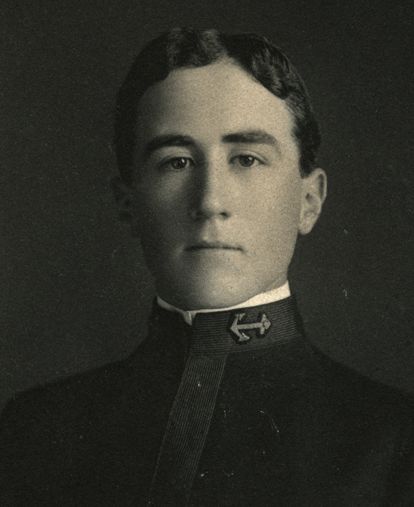

JAMES N. SUTTON, 2LT, USMC

James Sutton '08

James Nuttle Sutton was admitted to the Naval Academy from Portland, Oregon on May 10, 1904 at age 18 years 11 months.

He resigned on June 3, 1905.

Lucky Bag

James' name does not appear in the 1908 Lucky Bag.

Loss

From Find A Grave:

Marine Corps officials labeled it a suicide at the Naval Academy, but the young lieutenant's grieving mother called it a murder and a cover-up. According to a [2007] book, "A Soul on Trial: A Marine Corps Mystery at the Turn of the Twentieth Century," the mother wasn't delusional.

Judge Advocate Maj. Henry Leonard stated the Corps' position clearly during the second investigation into the 1907 death of 2nd Lt. James N. Sutton:

"The hallowed grave of a dead son is no more sacred than the grave of a military reputation and there are a great many military reputations at stake in this hearing."

"Maj. Leonard was very involved in a PR battle; that is what makes this story so dramatic," author Robin R. Cutler said last week in a telephone interview from her home in New York.

"When he transformed this into a trial (of the mother), or something similar to a trial, it was something unprecedented."

"He was trying to win over public opinion by trying to make her look like a fool, that she had no credibility at all," Ms. Cutler said.

In "A Soul on Trial," Ms. Cutler, a professional historian, looked at the Sutton case in light of larger social forces at work in the early 1900s, especially the growth of powerful metropolitan daily newspapers.

On the night of Oct. 12-13, 1907, Sutton, a lieutenant enrolled in the Marine Corps School of Application, which operated out of what is now called Halligan Hall at the Naval Academy, got into a fight with some other young officers.

He ran a short distance to his tent, located near College Creek, and came back with two pistols.

Sutton fired a couple of shots before the lieutenants wrestled him to the ground. The men later told investigators that Sutton felt remorse for his misconduct and pulled a pistol out from under his body and shot himself in the head.

Sutton also had a dent in one side of his skull that never got explained, and he didn't bleed from the gunshot, which caused his mother to conclude that her son was dead or dying by the time the shot was fired.

Rosa Sutton said her son's ghost visited her at the family home in Oregon, and told her he had been murdered.

Mrs. Sutton, a devout Roman Catholic who thought that suicides were doomed to eternal damnation, set out to show that her Jimmie hadn't deliberately killed himself.

The military quickly conducted an inquiry in 1907, but the investigation could serve as the very model of incompetence.

Investigators failed to call key witnesses, misplaced the lethal bullet, lost the victim's brain, didn't photograph the body and never thought to do a ballistics examination of the bullet to determine which .38 caliber revolver had killed Sutton.

The second investigation, convened in 1909 after constant clamoring by Mrs. Sutton, was held in the auditorium of what is now called Mahan Hall at the academy. It turned into a media circus, but was much more thorough.

A lieutenant with whom Sutton had struggled, Robert Adams, had testified in 1907 that Sutton was face-down when he killed himself. Now, Adams testified that Sutton was looking to one side when he pulled the trigger.

A medical expert testified that it would have been impossible for Sutton to reach around and shoot himself near the top of the skull while turned in the manner Adams described.

Just as it was becoming clear to the crowded audience - and to the press - that a group of Marine lieutenants had held Sutton to the ground and one of them shot the victim to death, Leonard, the one-armed Marine JAG officer, turned the hearing upside down by putting Mrs. Sutton in the witness chair and questioning her about communicating with her son's ghost.

Leonard later admitted he entered the court of inquiry with "a carefully thought out plan" to preserve the Marine Corps' reputation.

The Washington Evening Star said "the whole Marine Corps is on trial," and a story in the Oregon Daily Journal called the suicide theory "preposterous." Closer to home, The Evening Capital called for a thorough housecleaning in the Marine Corps.

Despite all the ink given to the Sutton case a century ago, it is now all but forgotten.

Naval Academy Museum senior curator James W. Cheevers, known for his encyclopedic knowledge of the Naval Academy, said he had never heard about the Sutton case, and Marine Corps Chief Historian Charles Melson said he knew nothing about the affair.

"Sutton wasn't around long enough to make the Marine Corps Registry except the death entry," Mr. Melson said.

Even the author, Ms. Cutler, 63 and a professional historian, said she was unaware of the Sutton case until the 1990s, when she was looking through family keepsakes and found a black mourning locket that contained a photo of Sutton and a lock of his hair.

It turned out that Jimmie Sutton had been the brother of Ms. Cutler's grandmother, and the National Archives had the transcript of the 1909 hearing.

Ms. Cutler has concluded that one of the young officers, probably Adams, shot Sutton in a case of second-degree murder.

"I think it was heat of passion," she said.

The Marine Corps changed its view of the case slightly following the second investigation, in 1909, and ruled that Sutton may have accidentally shot himself. That ruling gave Rosa Sutton eternal hope.

"His grave is in Arlington, a tiny little stone, under a huge tree," Ms. Cutler said of Sutton. "It doesn't even have his dates on it."

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

James was a student at the local high school when he was appointed to the Naval Academy by Senator Mitchell in 1903. He entered the Werntz preparatory school at Annapolis. Because of his dislike for the hazing custom, he resigned fourteen months later and returned to Portland. In 1906 he entered a marine service preparatory school and was appointed to regular duty by the president in March 1907.

James left a Saturday night dance at the academy with Lieutenants Robert E. Adams and Edward P. Roelker (Naval Academy non-graduate, Class of 1908.) They all lived in the same barracks and were driven home by a chauffeur. They got into an argument, and James went into the barracks to get two pistols. They said James drew one pistol which was wrestled from him. Adam's finger was clipped by a bullet, and Edward received a wound on his chest from a bullet that lodged in his drill-regular book in his pocket. Someone yelled that Roelker was dead, and they said that James used the second pistol to commit suicide. He was found dead in a road near the academy. Roelker was later court martialed for being drunk at a signal drill in late November and was dismissed from West Point.

James' father James was a prominent railroad man in Portland, and his mother was Rose. His sister Rose was very vocal at the ensuing inquests into James' death. She had married Army Lieutenant Hugh Almer Parker in 1901. She then married attorney Robert Randolph Hicks on December 18, 1919. She died sometime after 1951. James' sister Louisa married Harry Moore in 1914, then married Rose's ex-husband Hugh Parker, and then married Cornelius Bailey in 1940. His sister Daily May married Dick Wick Hall, and she died in 1930 as Mrs. Wood.

James' brother John R., aka Redondo “Don” B., graduated from West Point on May 26, 1913. He had been hazed while there, and James had written him a letter after the event. Redondo was one of the first Army aviators. He made his cross-country flight in May 1915, but was injured in a flying accident in August which killed George Knox, paymaster at Fort Sill. Redondo flew to Manila in 1916 and later resigned from the Army. In October 1918, he was engaged to Marion Tucker, but then married Mrs. Esther Wadsworth Kilmer in July 1919. Their son died at birth in May 1920.

Redondo resided at the Ritz Carlton in New York City and knew the Astors. In 1922 he was arrested for being involved in the “Domino club” brokerage plot with Alfred E. Lindsay and Dr. Knute Arvid Enlind. In November, he was sentenced from six months to three years at Blackwell's Island prison. In May 1923, he was arrested again on a furniture swindle. He moved to Mexico around 1935 and was a mining engineer for the Durango Silver Mines. He married Luz Maria, and their son was Jimmie Raphael Sutton. Redondo died in early October 1946 and is buried there.

Memorial Hall Error

Whether James was murdered or committed suicide (accidentally or otherwise) is irrelevant; neither is a criteria for inclusion in Memorial Hall.

James is one of 7 members of the Class of 1908 on Virtual Memorial Hall.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.