DIXIE KIEFER, COMO, USN

Dixie Kiefer '19

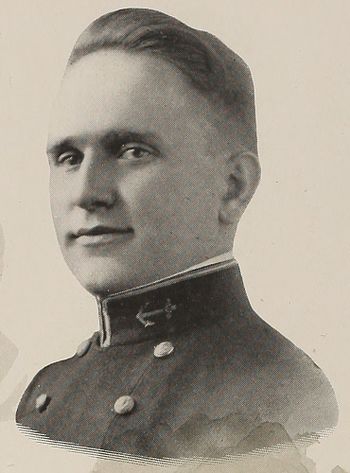

Lucky Bag

From the 1919 Lucky Bag:

Dixie Kiefer

Lincoln, Nebraska

"OH, look at the crowd over there!"

"Crowd—hell! That's not a crowd, that's Dixie Kiefer."

Dixie is the Academy Peter Pan, the boy who never grew up. If we attempted to even mention the number of incidents he has crowded into his career here, it would take volumes. How he saluted the doorman of the Hotel Knickerbocker, how he fell overboard when visiting the Admiral in the capacity of Skipper's orderly; how he had the class standing at attention two hours in the corridor owing to his penchant for fishing with a wastebasket in Youngster court; how he hid behind the piano in Rec Hall the day a fair inhabitant of our modern Athens came to see him; how—but enough.

We had picked Dixie for the class Red Mike, but he disappointed us. After two years spent here without even looking on at a hop, Dixie suddenly succumbed and began taking dancing lessons, and now he rivals Vernon Castle. It all goes to show that none of us are safe. But there were indications of his approaching fall. Reports began to circulate about an experience at that Modern Babylon, Ocean View, and when Dixie came back from September leave with a very knowing air and for him, a quiet demeanor, we knew that something was amiss.

Good-natured, impulsive, generous, he makes friends everywhere, and when he gets the ordeal of reporting aboard ship over with, he will make a good officer and, in an emergency, mighty fine ballast.

"Both rudders, full speed astern."

Honors: Buzzard; Plebe Football Team.

The Class of 1919 was graduated on June 6, 1918 due to World War I. The entirety of 2nd class (junior) year was removed from the curriculum.

Dixie Kiefer

Lincoln, Nebraska

"OH, look at the crowd over there!"

"Crowd—hell! That's not a crowd, that's Dixie Kiefer."

Dixie is the Academy Peter Pan, the boy who never grew up. If we attempted to even mention the number of incidents he has crowded into his career here, it would take volumes. How he saluted the doorman of the Hotel Knickerbocker, how he fell overboard when visiting the Admiral in the capacity of Skipper's orderly; how he had the class standing at attention two hours in the corridor owing to his penchant for fishing with a wastebasket in Youngster court; how he hid behind the piano in Rec Hall the day a fair inhabitant of our modern Athens came to see him; how—but enough.

We had picked Dixie for the class Red Mike, but he disappointed us. After two years spent here without even looking on at a hop, Dixie suddenly succumbed and began taking dancing lessons, and now he rivals Vernon Castle. It all goes to show that none of us are safe. But there were indications of his approaching fall. Reports began to circulate about an experience at that Modern Babylon, Ocean View, and when Dixie came back from September leave with a very knowing air and for him, a quiet demeanor, we knew that something was amiss.

Good-natured, impulsive, generous, he makes friends everywhere, and when he gets the ordeal of reporting aboard ship over with, he will make a good officer and, in an emergency, mighty fine ballast.

"Both rudders, full speed astern."

Honors: Buzzard; Plebe Football Team.

The Class of 1919 was graduated on June 6, 1918 due to World War I. The entirety of 2nd class (junior) year was removed from the curriculum.

Biography and Loss

From Naval History and Heritage Command:

Commodore Kiefer was born in Blackfoot, Idaho, on 4 April 1896 the son of E.C.W. Kiefer and Mrs. Tina W. (Glade) Kiefer. He attended Lincoln (Nebraska) High School, before his appointment to the US Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, from the First District of Nebraska in 1915. Graduated and commissioned Ensign in June 1918, with the Class of 1919, he progressed in grade until his promotion to Commodore, 24 May 1945.

After graduation from the Academy, he served in the USS St. Louis for a brief time until ordered to duty with the Destroyer Force based on Brest, France. He served in that assignment, in the USS Corona, USS Favorite and the USS Chesapeake, from August 1918 until October 1919. Following his return to the United States, he had duty in the USS Pennsylvania and the USS Nevada until June 1922 when he reported to the Naval Air Station, Pensacola, Florida, for flight training. Designated naval aviator 26 December 1922, he had served continuously with naval aviation from that time until his death in November 1945.

In April 1923, he reported to Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, and served until January 1926 with Observation Squadron 1, attached to the USS Aroostook, and with Observation Squadron 2, aviation unit of the USS California. Following duty as an Instructor at the Pensacola Naval Air Station for a year and one-half, he was under instruction in aeronautical engineering at the Postgraduate School, Annapolis, Maryland, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he received the degree Master of Science in June 1929. In October of that year he joined Scouting Squadron 3, based on the aircraft carrier Lexington, and in May 1930 was transferred to duty in the carrier Saratoga.

Between November 1931 and June 1934, he was on duty at Pearl Harbor, T.H., serving consecutively at the Fleet Air Base until August 1932; as operations officer, Aircraft Squadrons, until February 1933; and in command of Patrol Squadron 4, based there, until the completion of that tour. He next commanded Scouting Squadron 5, aviation unit of the USS Memphis, from June 1934 until June 1935, and the following two and one half years was engineer officer on the staff of Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, USS Wright, flagship, and later Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, with the USS Saratoga, as flagship. In January 1938, he rejoined the Wright as engineer officer on the staff of Commander, Aircraft, Scouting Force, serving in that assignment six months.

He was Inspector of Naval Aircraft, US Aircraft Corporation, Pratt and Whitney Division, East Hartford, Connecticut, from July 1938 until April 1941. In May of that year he returned to sea as executive officer of the Wright, serving in that capacity until 11 February 1942, when he was transferred to duty as executive officer of the USS Yorktown. During his duty aboard this carrier, which extended to 7 June 1942, when she was lost as the result of enemy action in the Battle of Midway where the Japanese Navy suffered its first decisive defeat in 350 years, the Yorktown also participated in the raids on Salamaua and Lae in March 1942, and in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May of that year. After serving in this carrier, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for "exceptionally meritorious service...(he) contributed greatly toward bringing the ship and her air group to a high state of morale, efficiency and readiness for battle exhibited by the Yorktown in her splendid contribution to the victory attained by our forces in the actions comprising the Battle of the Coral Sea..."

He was also awarded the Navy Cross for "extraordinary heroism as Executive Officer of the USS Yorktown in preparations for, during and after action against enemy Japanese forces in the Battle of Midway, on June 4, 1942. ...When the stricken vessel was being gutted by raging fires, he, being unable to obtain rescue breathing apparatus from his own smoke filled cabin, entered the photographic laboratory, which was a flaming inferno from burning films, and conducted the first fire-fighting there. Later, while directing the abandonment of the Yorktown, Commander Kiefer, in lowering an injured man into a life raft, burned his hands so severely that when he himself went over the side and descended by line, he was unable to support his own weight. In the resultant fall he struck the ship's armor belt and suffered a compound fracture of the foot and ankle. Despite acute pain, he gallantly swam alongside of and pushed a life raft toward a rescuing destroyer until he became so completely exhausted that he had to be pulled out of the water..."

Following the loss of the Yorktown, Commodore Kiefer was hospitalized until January 1943, when he assumed command of the Naval Air Station, Olathe, Kansas. He remained there until August 1943, interspersed with duty as Head of the Aviation Department at the Naval Academy between February and April 1943. Transferred to duty as Chief of Staff and Aide to the Chief of Naval Air Primary Training Command, Fairfax Airport, Kansas City, Kansas, and from November 1943 to January 1944 served as Acting Chief of that Command.

Detached from the Primary Training Command assignment at Kansas City in April 1944, he fitted out the USS Ticonderoga, assuming command of that aircraft carrier when she was commissioned May 1944. During his command, the Ticonderoga's Air Group inflicted heavy damage to the Japanese. Severely wounded when the Ticonderoga was twice struck by enemy suicide planes near Formosa on 21 January 1945, Commodore Kiefer remained on the bridge for twelve hours directed his heavily damaged ship. For his services in command of the Ticonderoga, he was awarded the Silver Star Medal "...On 21 January 1945 when his ship was severely damaged by enemy air attack, in spite of serious wounds, he remained on the bridge and continued to direct operations until his ship was out of danger from enemy action..."

He subsequently returned to the United States for hospitalization, and on 19 April 1945, reported for duty as Commander, Naval Air Bases, First Naval District, with additional duty as Commander, Naval Air Station, Quonset Point, Rhode Island.

Commodore Kiefer was killed in a plane crash in the Fishkill Mountains, Fishkill, New York, on 11 November 1945. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington Cemetery on 16 November 1945.

In addition to the Navy Cross, Distinguished Service Medal and the Silver Star Medal, and the Purple Heart Medal with Gold Star, Commodore Kiefer had the Victory Medal, Patrol Clasp (USS Corona); the American Defense Service Medal, Fleet Clasp (USS Wright); the American Campaign Medal; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two bronze stars; and the World War II Victory Medal.

From Wikipedia:

A second kamikaze hit Ticonderoga later that day. The explosion from that hit injured Kiefer, with 65 wounds from bomb shrapnel and a broken arm. Nonetheless he remained in command on the bridge for eleven hours.

While recovering from his injuries, Kiefer was made a Commodore in a ceremony at Rockefeller Center. He also served as commander of the Naval Air Station at Quonset, Rhode Island. He received the Distinguished Service Medal from Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, who called him "the indestructible man".

He had not yet recovered when he died at age 49 on 11 November 1945 - his arm was still in a cast. He was killed in the crash of his Navy transport plane on Mount Beacon, New York, while returning to Quonset from Caldwell, New Jersey.

Kiefer was said to be the most battered officer in the Navy. He broke his left ankle and split his kneecap playing football as a youth. His left elbow was smashed when a fellow pilot "buzzed" him in a seaplane and hit his arm with a wingtip float. The crew of Ticonderoga said of him, "He's got so much metal in him the ship's compass follows him when he walks across the deck."

He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. The chapel at the U.S. Naval Air Station at Quonset, R.I. was named the Dixie Kiefer Memorial Chapel. A plaque to his memory was placed in the chapel garden.

Photographs

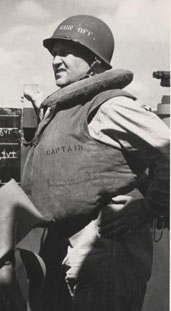

"Captain Dixie Kiefer in battle dress on the command bridge of USS Ticonderoga during the launching of aircraft against Luzon, Philippines, Nov 6, 1944." From Find A Grave.

Captain Dixie Kiefer, Commanding Officer, USS Ticonderoga (CV-14), on the bridge of his ship during an attack by Japanese planes off Manila, P.I., on 5 November 1944. Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command. Photo #: 80-G-469523.

Captain Dixie Kiefer, Ticonderoga's Commanding Officer, addressing the crew prior to being transferred to a hospital ship for medical treatment, in Ulithi Atoll, 25 January 1945. He had been injured when the ship was hit by a kamikaze on 21 January, while raiding Formosa. Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command. Photo #: 80-G-303151.

From Find A Grave

From Hall of Valor

Biography

From the June 2019 issue of Shipmate:

INDESTRUCTIBLE: DIXIE KIEFER

By Captain David Poyer ’71, USNR (Ret.)

Familiar to the homefront in World War II from movies and articles, Commodore Dixie Kiefer of the Class of 1919 might have led the Navy into the Atomic Age, but a tragic crash nearly erased him from our memories. Until now, when we celebrate and remember the life of Kiefer—100 years after his graduation.

You can still watch Dixie Kiefer at the climax of his career in the Academy Award-winning 1944 documentary “The Fighting Lady,” directed by the famous photographer Edward Steichen, as it was restored and colorized in 2012. In the movie, a pudgy and somewhat rumpled “Captain Dixie” addresses his crew: “Men, as soon as I finish talking, we are getting underway ... As you know, our final destination is a place called Tokyo. We’ll have to fight hard to get there; but when we drop our hook in Yokohama, I’m going to throw a party. All hands are cordially invited!”

The film reminds us of the most glorious days of the U.S. Navy, when the Carrier Navy redeemed all its promises by winning a Pacific war. The 75-year- old movie shows its age with cigarettes, pin-up girls and outmoded references to the enemy. The friendly, easy-going and party-throwing Kiefer was part of that action, “squat and chunky, not very much of a Hollywood type.” The movie also features Admiral John S. McCain Jr. ’31, USN.

Dixie (no middle name) Kiefer hailed from Blackfoot, ID, and went to high school in Lincoln, NE, before being appointed to the Naval Academy in 1915. His unusual name came from his Aunt Dixie. His Lucky Bag entry makes for puzzling reading: “Dixie is the Academy Peter Pan, the boy who never grew up. If we attempted to even mention the number of incidents he has crowded into his career here, it would take volumes. How he saluted the doorman of the Hotel Knickerbocker; how he fell overboard when visiting the Admiral in the capacity of Skipper's orderly; how he had the class standing at attention two hours in the corridor owing to his penchant for fishing with a wastebasket in Youngster court; how he hid behind the piano in Rec Hall the day a fair inhabitant of our modern Athens came to see him; how—but enough.” He also seemed to attract a good deal of flak for his weight, an affliction that would dog him throughout his career.

The Class of 1919 was graduated and commissioned a year early, in June 1918, because of the demands of World War I. Kiefer’s first assignment was to Corona, a converted motor yacht that escorted convoys and patrolled the Channel and French coast from 1917 until war’s end. Following that, he was assigned to a daunting undertaking: mine clearing duty. Not only were there 56,000 mines laid at varying depths across the notoriously stormy North Sea, but no one had ever swept for magnetic mines before, so technique and equipment had to be improvised.

When this dangerous operation concluded, Kiefer was ordered back to the U.S. for assignment aboard Pennsylvania. He served aboard the battleship for two years, and in 1922 he requested aviation duty.

The Navy was still feeling its way into aviation in the 1920s, and it was unclear which path led to the future—seaplanes, flying boats, wheeled aircraft or lighter-than-air dirigibles like the giant Shenandoah (ZR-1), commissioned around this time. After pilot training, Kiefer reported to Aircraft Squadron, Battle Fleet, as a seaplane pilot. He accomplished the first night takeoff from a battleship, being catapulted off California in a Vought UO-1 on 11 November 1924 in San Diego harbor.

After serving as an instructor in Pensacola, FL, and making recon flights over the great Mississippi Flood of 1927, Keifer requested postgraduate education. Though largely forgotten today, the Postgraduate Department had been active at the Academy since 1912, teaching ordnance, electrical engineering, radio, naval construction, civil engineering and marine and later aeronautical engineering. (The Naval Postgraduate School didn’t move to Monterey until 1951.) In 1929, following graduation, he reported to Lexington (CV-2), the Navy’s second purpose-built carrier.

Kiefer never married, unless you consider his single-minded dedication to the Navy a committed relationship. In the 1930s his career was interrupted by two accidents. In the first, he ran from his Pearl Harbor office to help extinguish a fire in a yard motorboat. In the second, a buddy in a seaplane buzzed him so low on Sara’s flight deck that the pontoon broke Dixie’s right arm.

By May of 1941, Kiefer was executive officer of Wright (AV-1), a dirigible tender reassigned to transport duty. Wright was underway between Midway and Pearl on 7 December, having just delivered building materials to Midway. In February 1942, the hefty and rumpled-looking Commander Kiefer became executive officer of Yorktown (CV- 5), beginning a wartime career that would make the bones he’d broken and fires he’d fought so far seem like just a warmup.

In another reminder of how different things were, though the Navy was officially as dry then as it is now, Kiefer convened regular drinking parties for pilots aboard the carrier. He called these social gatherings the “Yorktown Cocktail Club.”

Yorktown fought as part of Task Force 17 in the Battle of the Coral Sea in 1942 when U.S. and Imperial Japanese carrier groups clawed at each other in a tight, confused battlespace. On 8 May, Yorktown’s planes damaged the Japanese Shokaku. The counterstrike arrived that afternoon, and both Lexington and Yorktown were hit. The former eventually was lost, but after damage was contained aboard Yorktown, Kiefer convened another impromptu cocktail party. He received the Distinguished Service Medal for his “sound judgment, thorough planning and indefatigable zeal, unbounded enthusiasm and courageous example.”

Yorktown had survived, but when she arrived back at Pearl Harbor it was estimated that her repairs would take three months. But Admiral Chester Nimitz, USN, of the Class of 1905, needed every carrier afloat for a secret operation. He looked her over, and gave the yard a week. Meanwhile her exec was as busy as can be imagined, especially as he had to integrate new aircraft and crew. The ship was hastily patched in only three days and sent back to sea headed for Point Luck and immortality.

The Battle of Midway, as everyone knows, was the turning point of the Pacific War. It may have been four carriers to three, advantage Japan, but the Americans knew the enemy’s plans and routes in advance. Navy Air struck on 4 June 1942, setting on fire three Imperial Japanese Navy carriers. Hiryu’s counterstrike plastered Yorktown with three bombs. One knocked Kiefer to the flight deck, wounding him in the shoulder and leg. Running to the hangar deck, he realized the photo lab, crammed with flammable film and chemicals, was on fire. Grabbing a hose, he’d just knocked the fire down when torpedoes from bombers Nakajima B5N, “Kates” as termed by the Allies, slammed into the hull. With his ship losing power, flooding and listing hard, Captain Elliott Buckmaster, USN, of the Class of 1912, gave the order to abandon.

The story wasn’t over. When Yorktown was still afloat the next morning, Buckmaster sent Kiefer back aboard in charge of a damage control party to try to save her. Kiefer managed to stabilize her, but on 6 June, while under tow, Yorktown was torpedoed again by a Japanese submarine I-168. Kiefer had to abandon ship a second time, but this time he lost his grip on the line he was descending, stripping the skin from both palms and breaking a foot and ankle as he hit the armor belt on the way down. He kept fighting, though, to make sure the sailors in his rafts were picked up. Kiefer was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and Navy Cross for his heroism aboard Yorktown.

After his recovery and light duty at training commands in the continental United States, Kiefer took over as commanding officer of the newly constructed Ticonderoga (CV-14). She was commissioned in June 1944, when he gave the talk over the 1MC (1 Main Circuit, or shipboard public address) recorded in “The Fighting Lady.”

Kiefer’s command style as a commanding officer was about as far as possible from the style of then-Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King, USN, of the Class of 1901. King had a reputation of being “cold, aloof and impossibly demanding in many situations.” Dixie was jovial, approachable and enjoyed a strong cocktail and a good party. He often offered rides to enlisted men and glad-handed his way around the ship. He in no way condoned slackness; he trained his men hard, but also believed that sports, relaxation and the occasional drink together promoted bonding and eased wartime stress. When underway, the chunky “Cap’n Dixie” preferred the open bridge atop the island rather than the “forward conn.” There he would be protected by armor, but he could neither see nor inspire his men by being seen. He also addressed the crew on the 1MC several times a day, keeping them updated on the ship’s activities and plans.

After workups in the Caribbean and training at Pearl, Ticonderoga reached the western Pacific in October 1944.24 Operating from Ulithi Atoll with Task Force 38, through November and December she pounded Luzon, Japanese convoys and the Manila Bay area, dodging kamikazes but as yet untouched. Later that same month, Kiefer navigated Tico through the disastrous Typhoon Cobra that sank three other ships. He did so largely by disregarding the course orders of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, USN, of the Class of 1904, and steering out of the storm. In January, Tico carried out strikes on the Ryukyus and Formosa, Luzon, Indochina and Hong Kong, usually in bad weather. By that point in the war, the Navy seemed to have the run of the Pacific. But on 21 January 1945, Tico’s and Kiefer’s luck ran out.

The sky was clear, and Tico wasn’t even at general quarters when the dark silhouette of a dive bomber came out of the sun. It crashed through the flight deck near the Number Two 5-inch mount, angled down. The bomb it was carrying exploded just above the hangar deck, and nearby planes burst into flames. Burning aviation fuel ran down hatches, which had been built without coamings, spreading the fire to the decks below and putting the whole ship at risk.

The Dictionary of Fighting Ships reads: “Capt. Kiefer conned his ship smartly. First, he changed course to keep the wind from fanning the blaze. Then, he ordered magazines and other compartments flooded to prevent further explosions and to correct a 10-degree starboard list. Finally, he instructed the damage control party to continue flooding compartments on Ticonderoga’s port side. That operation induced a 10-degree port list which neatly dumped the fire overboard! Firefighters and plane handlers completed the job by dousing the flames and jettisoning burning aircraft.”

Meanwhile, other kamikazes continued to attack the burning Tico. Though most were shot down, another plane got through, hitting the flight deck again, this time at the base of the island. This second impact sprayed fragments and fire over the bridge area where Kiefer was fighting the ship from. The total damage count: wrecked radio and radar gear, 36 aircraft destroyed, and 143 dead and 202 wounded.

The wounded included Kiefer, who was severely hurt, with a compound fracture of the right arm and 65 other wounds on his head and other areas his flak jacket hadn’t protected. A medic tried to dress his bleeding gashes and got him to lie down on a mattress. But his executive officer had also been severely wounded, so Kiefer refused to leave the bridge for further treatment. In fact, despite pleas for him to go below, he stayed there for the next 11 or 12 hours, directing the firefighting and damage control.

Sometime during this period, the task force commander asked if Kiefer planned to abandon ship. Probably remembering YORKTOWN’s premature abandonment, Kiefer snapped to the radioman, “Hell, no.” He stayed on the bridge until midnight. “Only then, when someone reported that every injured man had now gotten medical attention, did Dixie Kiefer allow two corpsmen to lay him down on a stretcher and haul him down to sick bay.”

In Ulithi, Kiefer was transferred to Samaritan, a hospital ship. After recuperation at Naval Hospital Bethesda, MD, he was discharged and promoted to commodore in May 1945. Still typically modest, it was around this time he said, “I’m a professional man, just paying back the United States for a marvelous education and 30 years steady employment at a good job with good pay ... I’m not like the reserves who volunteered to go to war with far less training. There’s nothing heroic about us ‘regulars.’ We weren’t giving up homes, good jobs, pleasant shore lives to go to sea.”

The Secretary of the Navy, James V. Forrestal, called Kiefer “the indestructible man” when awarding him the Distinguished Service Medal for his heroism in the Pacific Theater. With his arm still in a cast and with several still-unhealed other wounds, he was assigned as commanding officer of Quonset Point Naval Air Station, where his mother and sister moved in with him. As commanding officer, he set up clambakes, skating and hunting parties, steak dinners and, of course, more happy hours.

But Dixie had a rendezvous with fate. In November 1945, he flew to Caldwell, NJ, in a Beechcraft Expeditor with several other servicemen to attend the Army-Notre Dame football game at Yankee Stadium. They left on their return flight on the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month (then Armistice Day, now Veterans Day). During the return flight, the plane crashed, 1,100 feet up the western flank of the north peak of Mt. Beacon, near the town of Fishkill, NY. None of the six men aboard survived. The bodies were so badly burned that Kiefer was identified by the cast on his arm and his ID tags.

Dixie Kiefer was buried with military honors in Arlington Cemetery on 16 November 1945. The new Quonset Point Chapel was named after him until the Naval Air Station closed down in 1975. A group of local residents, the Friends of the Mount Beacon Eight, make organized pilgrimages each year to the crash site, where the remains of the Expeditor can still be seen.40 With his stellar wartime record, Dixie Kiefer could have looked forward to flag rank in the postwar Navy. Certainly his peers, the other carrier captains, did well, many serving in high positions during the Korean War and afterward. His untimely death snipped his career short, and probably contributed to his memory being overshadowed by those who survived and flourished further. But Navy Air and our country still owe him recognition for his service in two wars, his bravery and the example he set. Jovial, easygoing and, yes, maybe a bit overweight, Dixie Kiefer was courageous in flight, resourceful in battle and, above all, loved by his men.

Like so many other unsung heroes, he deserves to be remembered. ⚓

A special thanks for this piece to David Rocco, who brought Kiefer’s career to Shipmate. With Don Keith, Rocco recently published The Indestructible Man (Erin Press, 2017), which covers Kiefer’s life far more extensively. Visit the Friends of the Mount Beacon Eight Facebook page for more information. Thanks are also due to Jennifer Bryan, director, Archives Division, and Lenore Hart. Dave Poyer ’71’s latest novel is Deep War (St. Martin’s, December 2018). It and his other novels featuring fictional USNA grad Dan Lenson are available in hardcover, paperback, ebook and audio, and Violent Peace will appear this fall. Visit his Facebook page or his website at www.poyer.com.

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander Dixie Kiefer, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Executive Officer of the Aircraft Carrier U.S.S. YORKTOWN (CV-5), in preparation for, during and after action against enemy Japanese forces in the Battle of Midway, on 4 June 1942. Through sound judgment, through planning and exceptional courage, Commander Kiefer contributed greatly toward the high state of readiness for battle which made it possible for the YORKTOWN to face the powerful bombing and torpedo attacks of the enemy with aggressive fighting spirit and enabled her Air Group to accomplish their hazardous missions with inspired efficiency. When the stricken vessel was being gutted by raging fires, he, being unable to obtain a rescue breathing apparatus from his own smoke-filled cabin, entered the photographic laboratory, which was a flaming inferno from burning films, and conducted the first fire-fighting there. Later, while directing the abandonment of the YORKTOWN, Commander Kiefer, in lowering an injured man into a life raft, burned his hands so severely that when he himself went over the side and descended the line, he was unable to support his own weight. In the resultant fall he struck the ship's armor belt and suffered a compound fracture of the foot and ankle. Despite acute pain, he gallantly swam alongside of and pushed a life raft toward a rescuing destroyer until he became so completely exhausted he had to be pulled out of the water. His courageous initiative and unselfish devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

General Orders: Board of Awards: Serial 19 (October 14, 1942)

Service: Navy

Division: U.S.S. Yorktown (CV-5)

Distinguished Service Medal

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Commander Dixie Kiefer (NSN: 0-34685), United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States as Executive Officer of the U.S.S. YORKTOWN (CV-5) in preparation for, during, and after battle. By his sound judgment, thorough planning and indefatigable zeal, unbounded enthusiasm and courageous example, he contributed greatly toward bringing his ship and her Air Group to the high state of desire to engage the enemy and her readiness for battle which enabled the Air Group to make three successive attacks on the enemy at Tulagi on 4 May 1942, to attack and sink an enemy carrier on 7 May 1942, and to attack and seriously damage an enemy carrier and to engage and destroy many enemy aircraft on 8 May 1942, and to hold to a minimum the damage received from an aerial bomb and many near misses, and finally, which enabled the ship and Air Group to come through these actions with aggressive fighting spirit undiminished.

General Orders: Commander in Chief Pacific: Serial 2885 (July 7, 1942)

Service: Navy

Rank: Commander

Silver Star

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Captain Dixie Kiefer (NSN: 0-34685), United States Navy, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as Commanding Officer of the Aircraft Carrier U.S.S. TICONDEROGA (CV-14). Captain Kiefer skillfully and courageously fought his ship in such manner as to contribute greatly to decisive victories over the enemy in the far western Pacific. On 21 January 1945 when his ship was severely damaged by enemy air attack, in spite of serious wounds, he remained on the bridge and continued to direct operations until his ship was out of danger from enemy action. His unfaltering determination and exceptional leadership inspired his officers and crew to perform outstandingly throughout these operations. His skill and courage were at all times in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

General Orders: Commander 1st Carrier Task Force Pacific: Serial 0338 (April 7, 1945)

Service: Navy

Rank: Captain

Dixie received a commendation from the Secretary of the Navy on April 12, 1930 for his role in a "search expedition" in Utah and Nevada for a missing Western Air Express pilot. From Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin No. 129 (April 26, 1930).

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together… or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

January 1919

January 1921

January 1922

May 1923

July 1923

November 1923

January 1924

March 1924

May 1924

October 1925

January 1926

October 1926

LT Paul Thompson '19

LT William Sample '19

LTjg William Butler, Jr. '20

LT Frederick Roberts '20

LTjg Rogers Ransehousen '21

LTjg Irving Wiltsie '21

January 1927

April 1927

October 1927

January 1928

April 1928

July 1928

October 1928

January 1929

April 1929

July 1929

October 1929

LT Arnold Isbell '21 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 1B)

LTjg Robert Larson '24 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 3B)

LTjg William Graham, Jr. '25 (USS Lexington)

LTjg Hilan Ebert '26 (USS Lexington)

ENS William Potts '27 (USS Lexington)

ENS John Yoho '29 (USS Lexington)

January 1930

LT Arnold Isbell '21 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 1B)

LTjg Robert Larson '24 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 3B)

LTjg William Graham, Jr. '25 (USS Lexington)

ENS William Potts '27 (USS Lexington)

ENS John Yoho '29 (USS Lexington)

April 1930

LT Arnold Isbell '21 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 1B)

LTjg Robert Larson '24 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 3B)

LTjg William Graham, Jr. '25 (USS Lexington)

ENS Robert Winters '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 1B)

ENS William Potts '27 (USS Lexington)

ENS John Yoho '29 (USS Lexington)

October 1930

LT William Sample '19 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 2B)

LTjg Walter Leach, Jr. '24 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Creighton Lankford '25 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 1B)

LTjg Carlton Hutchins '26 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Charles Signer '26 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Robert Symes '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg Renwick Calderhead '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg John Eldridge, Jr. '27 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 2B)

LTjg Julian Greer '27 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

ENS Weldon Hamilton '28 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

January 1931

LT William Sample '19 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 2B)

LTjg Walter Leach, Jr. '24 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Creighton Lankford '25 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 1B)

LTjg Carlton Hutchins '26 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Charles Signer '26 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Robert Symes '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg Renwick Calderhead '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg John Eldridge, Jr. '27 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 2B)

LTjg Julian Greer '27 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

ENS Weldon Hamilton '28 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

April 1931

LT William Sample '19 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 2B)

LTjg Walter Leach, Jr. '24 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Creighton Lankford '25 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 1B)

LTjg Carlton Hutchins '26 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Charles Signer '26 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Robert Symes '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg Renwick Calderhead '27 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg John Eldridge, Jr. '27 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 2B)

LTjg Julian Greer '27 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

ENS Weldon Hamilton '28 (Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

July 1931

October 1931

April 1932

October 1932

January 1933

April 1933

July 1933

October 1933

April 1934

July 1934

October 1934

January 1935

April 1935

October 1935

January 1936

April 1936

July 1936

January 1937

LT John Waldron '24 (USS Saratoga)

LT Richard Moss '24 (Bombing Plane Squadron (VB) 2B)

LT Gerald Dyson '27 (Bombing Plane Squadron (VB) 2B)

LTjg Leonard Southerland '27 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LT William Pye, Jr. '28 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg John Collett '29 (Torpedo Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg Thomas Ashworth, Jr. '31 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Clarence Kasparek '32 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 4B)

LTjg Albert Gates, Jr. '32 (USS Saratoga)

LTjg George Bellinger '32 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Edwin Hurst '32 (Bombing Plane Squadron (VB) 2B)

ENS Maurice Fitzgerald '35 (USS Saratoga)

April 1937

LT John Waldron '24 (USS Saratoga)

LT Richard Moss '24 (Bombing Plane Squadron (VB) 2B)

LT Gerald Dyson '27 (Bombing Plane Squadron (VB) 2B)

LT Leonard Southerland '27 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LT William Pye, Jr. '28 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg John Collett '29 (Torpedo Plane Squadron (VT) 2B)

LTjg Thomas Ashworth, Jr. '31 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Clarence Kasparek '32 (Scouting Plane Squadron (VS) 4B)

LTjg Albert Gates, Jr. '32 (USS Saratoga)

LTjg George Bellinger '32 (Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 6B)

LTjg Edwin Hurst '32 (Bombing Plane Squadron (VB) 2B)

ENS Maurice Fitzgerald '35 (USS Saratoga)

September 1937

LT John Waldron '24 (USS Saratoga)

LT Gerald Dyson '27 (USS Saratoga)

LT William Pye, Jr. '28 (Fighting Squadron (VF) 3)

LT Weldon Hamilton '28 (Bombing Squadron (VB) 3)

LTjg Edwin Hurst '32 (Bombing Squadron (VB) 3)

ENS Maurice Fitzgerald '35 (USS Saratoga)

ENS Paul Riley '37 (USS Saratoga)

ENS William Mason, Jr. '37 (USS Saratoga)

January 1938

LT John Waldron '24 (USS Saratoga)

LT Gerald Dyson '27 (USS Saratoga)

LT William Pye, Jr. '28 (Fighting Squadron (VF) 3)

LT Weldon Hamilton '28 (Bombing Squadron (VB) 3)

ENS Maurice Fitzgerald '35 (USS Saratoga)

ENS Paul Riley '37 (USS Saratoga)

ENS William Mason, Jr. '37 (USS Saratoga)

July 1938

January 1939

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

April 1941

Memorial Hall Error

The abbreviation for the rank of Commodore is "COMO"; Memorial Hall has "COMM" for Dixie (but "COMO" for James Logan '10).

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.