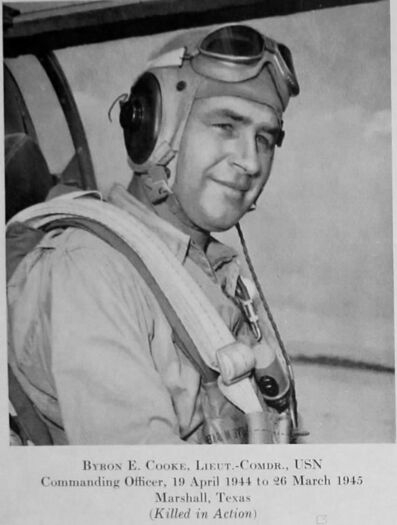

BYRON E. COOKE, LCDR, USN

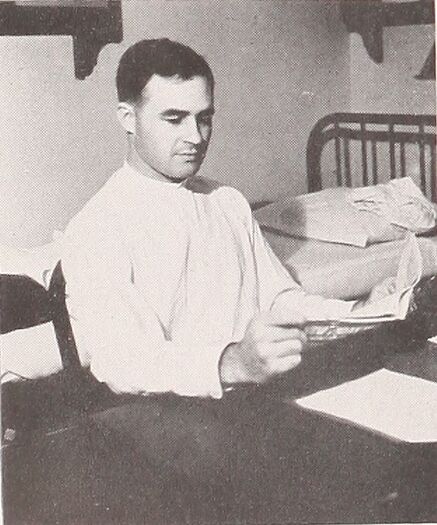

Byron Cooke '39

Lucky Bag

From the 1939 Lucky Bag:

BYRON EBERLE COOKE

Marshall, Texas

Cookie

His reticence and dry humor are his best qualities. Byron is one of those very quiet persons who seem to be taking in everything but never saying much about it. He hails from Texas, but has spent much time in Wyoming, where he worked on a dude ranch. Perhaps he picked up his silent demeanor in the West. His Navy career began as an enlisted man two years before he entered the Academy. Always at odds with the academic departments, he has defensively developed an uncanny ability for pulling sat with a minimum of effort. It is a very difficult task to make him talk; but once started, he has some good yarns. He is undistinguished mostly because he has never broken the siesta habit.

1 P.O.

BYRON EBERLE COOKE

Marshall, Texas

Cookie

His reticence and dry humor are his best qualities. Byron is one of those very quiet persons who seem to be taking in everything but never saying much about it. He hails from Texas, but has spent much time in Wyoming, where he worked on a dude ranch. Perhaps he picked up his silent demeanor in the West. His Navy career began as an enlisted man two years before he entered the Academy. Always at odds with the academic departments, he has defensively developed an uncanny ability for pulling sat with a minimum of effort. It is a very difficult task to make him talk; but once started, he has some good yarns. He is undistinguished mostly because he has never broken the siesta habit.

1 P.O.

Loss

Byron was lost when his TBM-3 Avenger collided with another over Okinawa on March 26, 1945. The two crewmen aboard were also lost; the other plane crash-landed on Okinawa. He was commanding officer of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 9, flying from USS Yorktown at the time.

Other Information

From researcher Kathy Franz:

Byron, who went by Eberle as a youth, and Cecil Pippen attended Camp Warren at Cheyenne, Wyoming in July 1930. In July 1931, Byron, Cecil and another friend were in San Antonio attending C. M. T. C. at Camp Bullis. Byron spent the summer of 1933 working in a CCC camp in Buffalo, Wyoming. He then went to the San Diego naval training school.

His father was Eberle, a farmer, mother Mary Elizabeth (Strange,) brothers Samuel and Fred, and sisters Mildred, Hattie, and Anna.

From The Marshall News Messenger, Texas, March 22, 1944:

Lieut. Byron Cooke, Torpedo Bomber Pilot, Back Home in Elysian Fields After Eight Big Pacific Engagements

By Elizabeth Hurley

A modest, unassuming hero, wearing no ribbons to indicate the eight major engagements in which he has participated as a torpedo bomber pilot aboard a U. S. aircraft carrier in the Pacific, came home this week.

Lieut. Byron E. Cooke of Elysian Fields, who for the past seven months has been in all of the major battles in the Pacific, talked about his experiences with calmness – with an attitude more of having done the job to which he was assigned than for any glory he might receive.

First Raid on Marcus

Although he has almost 11 years of navy service behind him, Cooke still felt a certain excitement when he took off from the flattop on his first combat mission last Aug. 31 – a raid on the Marcus Islands. From then on it was one raid after another – on Wake, Rabaul, the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, Truk, and Saipan in the Marianas.

What Cooke didn’t tell us but what we later learned from another authoritative source was about a thrilling and narrow escape he had while in the midst of Jap planes when the enemy force was attacking his ship at Rabaul.

With a Jap plane on their tail, the gunner’s turret stuck and he couldn’t fire. At the same time the innerplane radio got fouled and would not operate, so the turret gunner, T. S. Malikowski, of Chicopee, Mass., was unable to tell his pilot and naturally Cooke could not see the attacking plane.

Saved by Fighter

In the nick of time an American fighter pilot saw their predicament and shot down the Zero, which went up in flames just a few feet off the tail of Cooke’s plane.

Not until they landed safely back on the ship was the gunner able to inform Cooke of their narrow escape.

When we questioned Cooke about whether they shot down any planes or what they did during the Jap attack on their ship, he only replied, “We just did our best to stay out of the way and let the fighters take care of the Zeros.”

Cooke left the United States last May 10 as a member of Air Group Nine attached to a U. S. aircraft carrier. Since then his air group has piled up a record unsurpassed by any other group during the Pacific offensive which has snatched strategic bases from the Japs and plastered enemy shipping and military installations all over the Central Pacific.

Little more than three months later he took off on his first raid, which he said turned out to be mostly “target practice” as there was no enemy fighter opposition.

“Marcus didn’t have much to offer, no fighter defense,” Lieut. Cooke said, “It was just target practice for us and all the group returned safely. I think probably there was one plane lost that day, but it was from another carrier group, not ours.

“The island was very heavily bombed and we knew it would be of little use to the enemy as an airfield for quite awhile.”

Led by Comdr. Jack Raby of Pensacola, Fla., Cooke said the group hit Marcus in two strikes.

The first was launched about 5 a.m., just about an hour before sunrise. We were all at our battle stations, but I was not in the first group that took off. We had reveille about 2:30 a.m. and breakfast about 3:15. There was a certain bit of tensity, not much talk. Everyone had his own thoughts at that time. It was the first combat mission for practically all the men in our group. The fighter squadron had seen action in North Africa, but the rest of us were going out for the first time.

Beefsteak For Breakfast

“We had beefsteak for breakfast. They always gave us beefsteak for early morning breakfasts before battle and anything else they could save up for a hearty meal. Breakfast took about 45 minutes for the whole group; then we went to the ready room to don our flight gear, work out our navigation and receive last-minute instructions.

“The first group was gone about four hours. During that time we stayed around the ready rooms, drank coffee, ate sandwiches and listened to sports sent back by radio. Loudspeakers were rigged up in all departments and we were kept informed on the progress of the battle.

“The group met no opposition, dropped their bombs on the targets and came back about 9 or 9:30. It took awhile to rearm, re-gas the planes and reload them with bombs; then we took off about noon, circled the ship two or three times and departed. We were gone about four hours and met no opposition.

About a month later the group, part of a carrier task force, struck at Wake Island – on Oct. 5 and 6.

“We met opposition there, land-based Zeros,” Lieut. Cooke said, “but our fighters took care of them before we got there. About 30 or 40 Zeros were destroyed, some caught on the ground before they were able to take off. All planes in my squadron returned safely and I’m almost certain our group lost none. Only two or three planes in the whole task force failed to return. Our losses were very light.

“We played havoc with Wake. I believe they said we dropped about 800 or 900 tons of bombs on the island; however, there was terrific surface bombardment, too. Our ships were shelling the island while we dropped the bombs.

Never Saw a Zero

Lieut. Cooke said he took part in three raids those two days “but never saw a Zero.” He explained that each plane was assigned a specific target before starting out on raids and that his targets on his first two trips at Wake were warehouses. On his third trip he drew a service building near the airstrip.

“I know definitely that I hit the warehouses, but can’t say about the third as that raid was made about 30 minutes before sunrise and the visibility was not too good,” he said.

“During the two days, every building on the island that had been standing was destroyed – and there were a lot of buildings, too.”

When the task force was being assembled for the attack on Rabaul, Cooke said, his carrier unit was already at sea and was sent to join the assault. It was here that the carrier had its only narrow escape from the Japs during the entire seven months.

Ship Attacked by Japs

“Our group got to make only one strike at Rabaul. It was on Nov. 11 and our first attacking force took off about 8 a.m. We had returned and were planning another strike when the Japs attacked us.

“When they found our carrier unit, all our fighters and torpedo planes had taken off but the bombers were still on deck. I was in the air with the rest of my squadron when the Jap divebombers and torpedo planes swarmed in. We let our fighters take care of the Jap divebombers and we tried to intercept the torpedo planes as they came in.

“The attack lasted about 45 minutes before they were driven off and not a single Jap bomb had hit our ship. It was a very lucky action for us.

Praises Fighter Squadron

Cooke warmly praised his group’s fighter squadron.

“We had the best fighter squadron that has ever been out,” he said. “They made a wonderful reputation. In that one afternoon at Rabaul they shot down 46 planes and during the entire seven-month operations I’d say they got between 100 and 120. They were tops.”

Two days after the Rabaul raid naval commanders announced that three enemy warships were sunk, 12 others damaged and 24 planes shot down in the attack on the harbor and that in addition 64 or 70 Jap Zeros, torpedo planes and divebombers had been shot down when they attacked a U. S. carrier unit.

The day after the attack Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific fleet, announced at Pearl Harbor that “henceforth we propose to give the Jap no rest.”

And Air Group Nine did its big share to follow up that statement. Next came the raid preliminary to the invasion of the Gilberts.

Pre-Invasion Raids

“We bombed our targets there for two days before troops started landing and continued our raids all the time the landings were in progress. These were what we called support missions. We’d get instructions from the invasion forces on the group on certain targets they wanted us to hit; then we’d drop our bombs and return to our ship. We stayed with this until the landings were secure. Our group’s specific target was the airstrip on Betio and we hit that exclusively.

“On the way back to our base we took a stab at the Marshalls – what you might call a hit-and-run raid. We hit shipping in Kwajalein lagoon, damaged a number of ships and left two cruisers burning.

“Our next objective was the Marshalls. Our part of this assault lasted only five days, during which we lost only one plane, but the crew was saved. The pilot landed in the water near a destroyer and they were picked up immediately.

Best Job at Kwajalein

“I think we did our best job in supporting landings at Kwajalein. We kept up our attacks until the landings were secured; then the entire carrier task force went on to strike our surprise blow at Truk. Again we caught the Japs off guard and had very little opposition.

“After Truk we hit Saipan in the Marianas on Feb. 22, and that wound up our group’s raids. We headed back to port and home for leaves and reassignment.”

Cooke said he never lost a crew member and had no close calls “that I knew about” during the seven months of action.

“Sometimes I’d fly too low and get rifle slugs in the plane, but I didn’t know about it until I returned. At Tarawa I flew too low and a rifle slug hit my propeller and spattered oil all over the windshield. I had to make a deferred forced landing, but that was all.”

Sounded Like Pleasure Cruise

Cooke’s last visit home was in September, 1942. His letters home never gave his mother, Mrs. E. C. Cooke of Elysian Fields, an inkling about the big raids in which he was participating.

“He never wrote home about what he was doing,” she said. “His letters sounded like he was on a pleasure cruise. The only thing I knew about was Rabaul. I had read about that in the Marshall paper.”

Cooke joined the navy about a year after he graduated from high school at Elysian Fields, where he was born, and spent 21 months as a gob before he won an appointment to the U. S. Naval Academy after taking a preparatory course and test at Norfolk. He graduated from Annapolis in June, 1939, and went to sea. He had two and half more years of sea duty before war was declared and was on the Battleship Texas in port at Portland, Me., when the Japs attacked Pearl Harbor.

About a month later he was detached and sent to Pensacola for flight training and received his wings at Miami the following August. From there he took advanced training at San Diego and Norfolk.

Married Pensacola Girl

In November that year, he returned to Pensacola and married. His wife has been making her home with her sister in Seattle in order to be nearby when he returned to the States. She joined him at San Francisco after his return and they arrived home this week to visit his mother.

The ribbons he doesn’t wear are National Defense Service ribbon, American Theater of Operations, and Pacific Campaign ribbon which now has four stars for Marcus, Wake, Rabaul and the Gilberts. He has yet to add his two engagements in the Marshalls, Truk and the Marianas.

When Lieut. Cooke returns to his new assignment following his 25-day leave, he will be squadron commander of his same torpedo squadron, of which he has been executive officer. He doesn’t know now, but hopes he’ll get to go back to his same ship.

On February 16, 1945, Byron "knocked down one enemy plane with his propeller and limped back to the ship."

His wife was listed as next of kin.

He has a memory marker in Arlington National Cemetery.

Photographs

Distinguished Flying Cross

From Hall of Valor:

Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Lieutenant Commander Byron E. Cooke, United States Navy, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (Posthumously) for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as a Pilot in Torpedo Squadron NINE (VT-9), embarked in U.S.S. YORKTOWN (CV-10), over Truk Atoll on 16 and 17 February 1944.

General Orders: Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin No. 361 (March 1947)

Action Date: February 16 & 17, 1944

Service: Navy

Rank: Lieutenant Commander

Battalion: Torpedo Squadron 9 (VT-9)

Division: U.S.S. Yorktown (CV-10)

From Hall of Valor:

(Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Lieutenant Commander Byron E. Cooke, United States Navy, was awarded a Gold Star in lieu of a Second Award of the Distinguished Flying Cross for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight during World War II.

Action Date: World War II

Service: Navy

Rank: Lieutenant Commander

From Hall of Valor:

(Citation Needed) - SYNOPSIS: Lieutenant Commander Byron E. Cooke, United States Navy, was awarded a Second Gold Star in lieu of a Third Award of the Distinguished Flying Cross (Posthumously) for extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as Commanding Officer of Torpedo Squadron NINE (VT-9), embarked in U.S.S. Yorktown, on 19 November 1944.

General Orders: Bureau of Naval Personnel Information Bulletin No. 348 (March 1946)

Action Date: March 19, 1945

Service: Navy

Rank: Lieutenant Commander

Company: Torpedo Squadron 9 (VT-9)

Division: U.S.S. Yorktown

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together… or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

Related Articles

Philip Torrey, Jr. '34 was Byron's commanding officer as Carrier Air Group (CAG) 9. Executive officer of a sister squadron in the air group was Milton Jacobs '41, who was killed in action only a few weeks later.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.