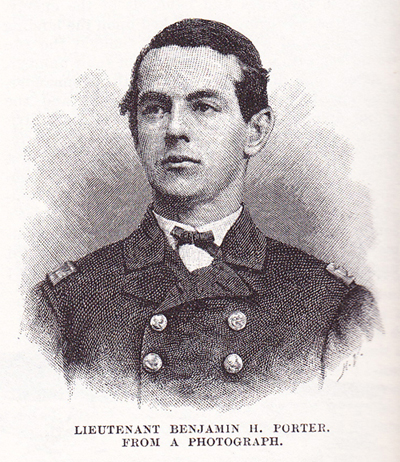

BENJAMIN H. PORTER, LT, USN

Benjamin Porter '63

Benjamin Horton Porter was admitted to the Naval Academy from New York on November 29, 1859 at age 15 years 4 months.

Loss

Benjamin was killed in action on January 15, 1865 during the Second Battle of Fort Fisher. He was commanding officer of USS Malvern (1860), which was the flagship of Admiral David Dixon Porter (no relation). He was leading a ground assault when he was killed by small arms fire.

Other Information

From Skaneateles:

Benjamin Horton Porter was born in Skaneateles on the 10th of July, 1844, the son of James Gurdon Porter and Sarah Grosvenor Porter.

In 1848, when Ben was four, his father moved the family to Lockport, N.Y., following the prosperity of the Erie Canal. Lockport had grown from a three-family settlement in 1820 to a town of 3,000 residents in 1825. One of James Gurdon Porter’s early business ventures was creating the city’s first gasworks in 1851.

Ben Porter was educated in Lockport, and remembered as “remarkable for his cheerful, amiable and affectionate spirit, which rendered him a universal favorite.” Like many adventurous boys, he dreamed of a life at sea. When he was 15, a vacancy occurred in his district for the United States Naval School at Annapolis, and friends urged him to apply. Silas M. Burroughs, the member of Congress for that district, held a competitive examination for all of the young applicants, and Ben Porter placed first.

Upon arriving at the Academy in November, 1859, he was given another examination; half the class examined with him was sent home; Porter was admitted as a cadet, and placed upon the school-ship Plymouth, anchored in Chesapeake Bay. He wrote to a friend, “Just think of my being here, going to school and the government paying me $30 a month for my company. Ain’t it bunkum?”

There were 112 cadets in Porter’s class. In June, they sailed on the annual cruise to initiate them into the practical duties of seamanship, visiting the Azores, Spain, the Rock of Gibraltar, Madeira, and the Canary Islands. They returned to Chesapeake Bay in September, where the sailors resumed their studies on shore for the winter.

In his enjoyment of college life, Ben Porter was not unlike many other students. To a friend, he wrote:

Last Saturday, I sent one of the servants out into town to get some oysters. After ‘taps,’ at night, we got out our chafing-dish, crackers, butter, pepper and salt. I got down under my bed, and took the chafing-dish with me. After all was ready, P_____ and H_______ hauled down the bedclothes over the front part of the bed, so the light could not reflect from the opposite wall out of the window… I struck the light and lay down on the floor to wait for the oysters to cook. After they were cooked, we drew the table up to the window and then commenced the fun! We ate a quart at this time, and as soon as we had finished we cooked another quart and ate them.

However, it was the eve of the Civil War and in eastern Maryland many people advocated secession from the Union, including some officers and cadets of the school. It was feared that those supporting the cause of the Confederacy might seize the ship, the guns and other property of the Naval Academy. The officers and cadets who remained loyal stood guard night and day; Porter himself stopped the hijacking of a small boat by firing his gun and summoning a guard.

Eventually, Federal troops arrived in relief, and Washington ordered the cadets to board the U.S.S. Constitution and sail for Newport, Rhode Island, where the school was re-established in a resort hotel, safe from “the assaults of treason.”

[The war began…]

Ben Porter, then 16, was assigned to the U.S.S. Roanoke on blockade duty off the Atlantic coast. (And here is your Small World factoid for the day: Porter’s commanding officer on the Roanoke was Capt. Charles Henry Poor, who, after his retirement, would spend his summers at Willowbank, also known as The Poor House, a house that he and his wife had received as a wedding present from her father many years before, today the big white house on Genesee Street at the foot of Leitch Avenue in Skaneateles.)

However, the Roanoke was soon back in port for repairs, and Porter wanted to get back into action. The Burnside expedition was then fitting out for the waters of the North Carolina, where goods were flowing into the Confederacy through its porous coastline.

The Union Navy and the forces of the Confederacy both realized that the Outer Banks and Roanoke Island were key to the Southern defenses and also a back door to the naval base at Norfolk, Virginia. Porter volunteered for the expedition and was accepted. Although young, he was given command of six launches, each with howitzers, for service in shallow water and on land.

On the 7th of February, 1862, the expedition landed on Roanoke Island. Porter and his sailors dragged their guns through a swamp to a position where he could protect the other troops who had landed; there they stood guard all night, drenched by a northeast storm. At daylight, they advanced on a line with the skirmishers. The Confederate hopes were pinned on a small three-gun battery in the center of the island. Porter later wrote:

As soon as I saw the enemy’s fortification I halted and… opened fire on the enemy with grape and shell from the rifled guns, and canister, shrapnel, and shell from the smooth bore… As I had received orders to keep the artillery on a line with the infantry, I advanced the pieces after each fire until they were in the open space directly in front of the rebel battery, where we made a stand under a most destructive fire from the rebel infantry. The men, however, worked the guns with great coolness and determination… We had been firing about three and a half hours when the fortification was stormed, and the rebels retreated.

Porter continued firing the howitzers even after most of his men had fallen and just one man remained with him. Porter wrote to his mother: “He alone remained, when a slug passed into his throat, from which the blood streamed out; he looked in my face, choked, fell down, and died. This made me madder than ever, and I went in on my muscle.”

Afterwards, General John Foster gave a tribute of commendation, saying: “I would notice here the gallant conduct of Midshipman Benjamin H. Porter, who commanded the light guns from the ships’ launches, and was constantly under fire.”

After the battle of Roanoke, he made a short visit to New York, where [the picture of him standing with his cover in his right hand] was taken, probably at the studio of Mathew Brady. His fame had gone before him. He took a room at the Metropolitan Hotel but it soon became known that he was “the young hero of Roanoke.” His celebrity annoyed him and he moved to another hotel.

Returning to duty after this brief respite, he was promoted to Acting Master and placed in command of the gunboat Ellis, patrolling the rivers, bays and inlets of North Carolina. One day he pursued a rebel craft and captured the crew. As they were brought onto the Ellis, one prisoner was found to be mortally wounded. He was one of Porter’s classmates at Annapolis. [This would be William Jackson '63.] He had the captive taken to his own room, and stayed by his side until he died.

In November, 1862, he was ordered to report to Admiral Samuel DuPont, at Port Royal, South Carolina. Here he was again in the blockade service, on the U.S.S. Canandaigua. But there was no getting away from Charleston and Fort Sumter. The Union Navy wanted Charleston harbor, but Fort Sumter was still in the hands of the rebels. And the Confederates were filling the channel-way of the harbor with “all manner of torpedoes [mines] and infernal machines.”

In July, 1863, Porter was selected to explore the harbor under the cover of darkness and search out its obstructions. For 24 nights in a row, he and his men were exposed to mines, picket boats, gunboats, the fort and the batteries of the enemy. Porter lost a pound every day and some nights had to be carried from the returning boat to his quarters. Author John S.C. Abbott described a typical night’s work:

He stood in the bow of the boat, in darkness which was only illumined by the flash of the guns, with his boat-hook feeling for and dodging torpedoes. At length he came across a buoy. Not knowing but that it was attached to a torpedo, he carefully approached and threw a rope over it, and then, backing some distance, he pulled upon it. As it proved to be harmless he again approached, and feeling with his boat-hook found it supported a large chain. Following the chain under water he soon came to other buoys and timbers, stretching across the channel. Following these up he found the opening for blockade-runners. Carefully making observations, to be sure of finding it again, he returned to the fleet and reported to the Admiral, offering to pilot the Monitors through.

And on another night:

With muffled oars and a strong pull he came rushing back to one of the Union Monitors with the tidings that a rebel steamer was under way and was coming down the harbor… Suddenly the rebel steamer emerged from the darkness, rushing down directly upon a scout-boat… The rebel steamer caught sight of the boat, fired a gun into her, and dashing on, struck the boat on the bow, breaking her to pieces. The men leaped into the water, and, as the steamer swept by, volleys of musketry were fired upon them while struggling in the waves.

Ensign Porter, hearing the report of the howitzer, the firing of the musketry, and the cry of the drowning… ordered his men to bend to their oars to rescue the crew. Eight he dragged from the water into his boat. Porter, with apparently as much coolness as if in his father’s parlor, flashed the light of his dark lantern all around over the waves to ascertain if any more drowning men could be discovered, though he knew those gleams would guide the on-rushing rebel steamer down upon him. The flash of his lantern revealed to him the steamer heading directly for his boat. But the light of Porter’s lamp had also revealed the rebel gun-boat to the Catskill, and she opened upon her with her ponderous guns. The gun-boat could not for a moment cope with such an antagonist, and putting on all steam she fled back into the harbor, while at the same moment young Porter, with the rescued crew, plunged into the gloom of the storm and of the night, and returned to the fleet in safety.

After an hour or two of sleep, Porter would be again be found on the gun-deck, commanding his section of guns in action, stripped to shirt and trousers, black with smoke and powder, sighting every gun.

Battered as [Fort Sumter] was, it was still manned by Confederate troops and artillery. The U.S. Navy men had observed a breach in the wall, and a plan was hatched to storm the fort by night. Porter volunteered.

Thirty boats, carrying 700 men, were collected. But the rebels had observed the preparations and were ready to meet the assault.

John S.C. Abbott wrote:

In the darkness of the night stealthily the boats approached Fort Sumter. Suddenly there burst upon them such a storm of iron and of lead from the garrison, the gun-boats, and the batteries as no mortal valor could withstand. This tornado of war swept every boat back but three. One of these three was commanded by Benjamin H. Porter.

These three boats reached the debris of the fort. A hundred men sprang from them upon the broken mound of brick and stone, with the deafening thunder of artillery filling the air, and with round shot, grape-shot, and hand-grenades flying in all directions around them. The wounded, the dead, and trails of blood marked their path as they ascended the rugged acclivity a distance of forty feet.

Here they unexpectedly encountered a perpendicular wall 16 feet high, with its top crowded with rebel sharp-shooters who threw down hand-grenades which, bursting in the boats, blew them to pieces. These grenades also fell with fearful destruction into the disordered ranks of the assailants. At the same time fire-balls were thrown down which lighted up the whole scene as bright as day, enabling the garrison to take unerring aim at the little handful of men.

Porter and his remaining men were forced to surrender and were marched into the fort as captives.

The commander received them in his rubble-strewn domain with courtesy, saying, “Gentlemen, you are unexpected guests. But I will entertain you to the best of my ability.” The next day they were allowed to send to the fleet for clothing and money, and were sent by steamer to Charleston, then to Columbia, South Carolina.

For the next fourteen months, Benjamin Porter was in prison, and for several months in irons. Porter wrote to his father:

Lieutenant E. P. Williams and myself are in irons and close confinement, held as hostages for Acting-Masters Braile and McGuire, of the Southern navy, now, as I am informed, confined at Fort McHenry to be tried as pirates. I wish you would see what you can do for me ; for although we are as comfortable as can be under the circumstances, still we are far from being comfortable.

A young lady in Columbia had known Porter in Lockport and learned he was in the prison. She asked to see him, but was refused. She did, however, persuade the friends of a rebel officer who was confined on Johnson’s Island, in Lake Erie, to pay Porter $300, upon his promise that his friends in the North would give $300 to their relative. This was done and the money contributed to his comfort. He managed to get some old naval books on navigation, math and geometry, saying he intended to be the first in his class, on examination, when exchanged.

Another inmate, Captain Shadrack T. Harris, was in irons in a room opening on one in which the naval officers of the Sumter expedition were confined. Porter succeeded with his jack-knife in springing the lock of the door of Captain Harris’s room and taught him how to slip his irons off and on again. This was a huge relief, as Harris could slip them on only when the jailer was about to enter the room.

In October, 1864, an arrangement was made for the exchange of the naval officers and men captured at Fort Sumter. Mr. Porter gave all his money and spare clothes to another prisoner before leaving.

On arriving at Richmond he was placed in Libby Prison, and after ten days was sent on to the Union lines. He arrived in Washington the next day, reported to the Navy Department, then went to New York. He had been at home in Lockport for two days when a telegram from the Department announced that his exchange was official, and summoned him to report to Admiral David Porter. He was warmly received, and placed in command of the Admiral’s flag-ship, the U.S.S. Malvern.

The next objective was Fort Fisher, guarding Wilmington, North Carolina, on the Cape Fear River. This was the last open port of the Confederacy and vital to its survival. Steamers ran cargoes of cotton and tobacco through the blockade to ports in the Bahamas, Bermuda or Cuba, where the goods were exchanged for food and munitions for General Robert E. Lee’s army.

Fort Fisher, built on a peninsula where the Cape Fear River met the sea, protected Wilmington and harried the blockading Union ships with 44 heavy cannons. One hundred and twenty-five more cannons and 1500 soldiers defended the fort against any land or sea attack. Its commander, Colonel William Lamb, modeled it after the Malakoff Tower, a famed Crimean War fortification in Sevastopol, Russia.

Just before the conflict Ben Porter wrote to his mother:

We are now off New Inlet once more, for the purpose of taking Fort Fisher ; and this time, by God’s blessing, we mean to do it. We have General [Alfred] Terry in command, and he is young and ambitious. I hope he will make his men fight. It is 4 o’clock in the morning, and we are moving in for the attack.

And he wrote to a young friend:

I am going ashore to lead my men to the charge on Fort Fisher… I have been in command of the flag-ship several weeks, and am very pleasantly situated. I expect that we shall have a very hard fight, and as I am going to assault the fort, I run a good chance of losing the number of my mess [a navy idiom for dying].

Upon arrival at the waters off Fort Fisher, Admiral Porter asked for volunteers for an assault on the sea side of the fortress. Admiral Porter’s order to the force was “Board in a manly fashion!” Ben Porter would lead the volunteers from the U.S.S. Malvern. He was armed with a pistol and a cutlass, but chose instead to carry the Admiral’s flag.

The ships of the naval detachment fired on the fort all morning while the Army and Navy landed their men to the north of the fort. Of the bombardment, William Cushing later wrote, “Such a hell of noise I never expect to hear again. Hundreds of shell[s] were in the air at once . . . all shrieking in a grand martial chorus that was a fitting accompaniment to the death dance of the hundreds about to fall.”

On the beach, Porter waited with his fellow officers, William Cushing and Samuel Preston. Preston produced a bottle of beer from his coat pocket; the three men drank a toast to a young lady of their acquaintance, and looked at Fort Fisher waiting for them across the sand.

At 3 p.m. the signal to cease firing was sent to the fleet, the ships blew their steam whistles to signal the beginning of the land assault. This was supposed to be a phased charge, with Marine sharpshooters giving cover to the sailors, and the Army advancing from the north, but in the noise and confusion, the sailors all charged at once, running in ankle-deep sand toward a nine-foot palisade, with even higher parapets beyond, where Confederate soldiers waited with a thousand rifles and cannons to kill them.

Because the Army was advancing through a wooded area, the defenders didn’t see them at first and so concentrated their fire on the naval attackers. Confederate General Whiting stood on the ramparts of the fort, barking orders, cursing and challenging his men to kill the enemy. Although wounded four times, a naval ensign, Robley Evans, survived, and his account tells us what Ben Porter and his companions experienced:

About five hundred yards from the fort, the head of the column suddenly stopped, and, as if by magic, the whole mass of men went down like a row of falling bricks… At about three hundred yards they again went down, this time under the effect of canister [grape shot from the cannons] added to the rifle fire. Again we rallied them, and once more started to the front under a perfect hail of lead, with men dropping rapidly in every direction.

George Dewey, who as Admiral Dewey would become famous at the battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War, witnessed the charge as the Executive Officer aboard the USS Colorado. This is his account:

We could see very clearly the naval detachment which had landed under the face of the fort. The seamen were to make the assault, while the marines covered their advance by musketry from the trenches which they had thrown up. For weapons the seamen had only cutlasses and revolvers, which evidently were chosen with the idea that storming the face of the strongest work in the Civil War was the same sort of operation as boarding a frigate in 1812. Such an attempt was sheer, murderous madness. But the seamen had been told to go and they went. In face of a furious musketry fire which they had no way of answering they rushed to within fifty yards of the parapet. Three times they closed up their shattered ranks and attempted another charge, but could gain little more ground.

Of the 2,000 men who began the charge, fewer than 200 reached the palisade. When they looked over their shoulders, they saw that those who had started with them were either dead, wounded or just gone, and they fled for their lives as well. The only survivor of the three young officers, Lieutenant W. B. Cushing, described Ben Porter’s last moments:

Ben looked grave and determined, and I remember being much impressed by his supremely noble bearing. In a moment we were under a terrific fire, and the men commenced to get confused. It needed all the pluck and daring that man can have to lead and give confidence to the sailors in charging up that bare and level beach. Ben threw himself to the front, flag in hand, and the charge went on. We were all three in uniform, perhaps rashly, but it has ever been the pride of naval officers to wear, amidst the smoke of battle, the same lace that denotes their rank when enjoying the pleasures of society.

At the palisade, by the ditch that surrounds the fort, Ben fell, shot through the breast. His last words were, ‘Carry me down to the beach.’ Four of the Malvern‘s and Monticello‘s men raised him and tried to comply. Two were killed. He waved the others aside with a last motion, and died, with as sweet a smile as I could paint with words. I doubt not that some world met his dying eyes where spirits so pure, so noble, so brave as his meet with an eternal and great reward.

Confederate defenders along the Northeast Bastion cheered wildly. Their celebration evaporated, however, when Lamb and Whiting turned, stunned to see several large Union flags waving over the western salient of Fort Fisher.

On the land side, General Terry’s troops had captured the end of a parapet and began a hand-to-hand battle inside the fort that would last until dark, and end with the capture of the fort, opening the way to Wilmington.

After the battle, Admiral Porter wrote to Porter’s bereaved mother:

Your gallant son was my beau-ideal of an officer. His heart was filled with gallantry and love of country. It must be a dreadful blow to lose such a son. It was a dreadful blow to me to lose such an officer. My associations with my officers are not those of a commander. We are like comrades, and form fond attachments to each other. When they fall I feel as if I had lost one of my own family. Your son was captain of my flag-ship, and a favorite with me and all who knew him. He was brave to a fault.

Another officer wrote of Porter:

His imperial spirit gave him perfect command of his men; his youthful appearance and almost feminine beauty won their love ; his utter fearlessness commanded their admiration and roused their enthusiasm. He possessed that rare electric power, so singularly developed by Napoleon, which bound his men to him with almost a supernatural affection. It was said that there was not one of his men who would not readily have died for him.

Just after midnight on January 16, 1865, almost 14 hours after the sailors went ashore to participate in the attack, the bodies of young Lieutenant Porter and Flag. Lt. Samuel W. Preston were returned to the Malvern “and properly cared for.” Later that morning, with the ship’s flags at half-mast, Ensign John Gratton viewed his friends for the last time, and wrote of Porter, “A calm, peaceful smile played around his mouth.”

At 2:30 in the afternoon, in a cold, drizzling rain, the fallen officers were placed aboard the Santiago de Cuba for the journey north. The body of Lieutenant Porter, in a metallic case, was forwarded to his friends in New York. Navy officials wanted to honor his memory with a public funeral, but, “The grief of his friends was so deep that they had no heart for the public display.”

From researcher Kathy Franz:

On Benjamin's last visit home, Mr. Graves, a “photographist,” took a life-like likeness of Benjamin and had it hanging in his gallery Graves & Co in Lockport, New York. In 1866 Benjamin's father presented his portrait to be hung in the Ben. H. Porter ship.

In April 1867, Harper's Magazine published a story by John C. S. Abbott on Benjamin's life. The Lockport newspaper published the whole story in its edition.

The American Legion Post No. 164 in Skaneateles was named for Benjamin.

Benjamin's father James, who was heavily involved in civic affairs, was a merchant and one-time mayor of Lockport. He married Sarah Grosvenor in September 1829. Sarah's father was Captain George Grosvenor, and her grandfather was Seth Grosvenor who died in 1857 with a $2 million estate. In his will, he left Sarah $20,000 and her son Seth Grosvenor Porter $5,000. Sarah died at her daughter Laura's house in 1882.

Benjamin's siblings were Lucia who died at age 3, Laura, Seth, Samuel, Henry, Frederick, Stanley, and Maria.

Laura married Cornelius Van Schaak Roosevelt in 1853. As such, she became the aunt of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Seth became a sea captain. In 1875, he commanded the steamer Andes of the Atlas line running between New York and South America. He was offered command of the steamer Baltic by the White Star line which he refused. He retired and lived with his sister Laura from 1875-1900 when she died. He died in October 1910 in Stuttgart, Germany.

Frederick drowned in the Skaneateles Lake at the age of 12. He was going to use a skiff to cross the lake, but the boat overturned, and he was found on his back near the dock in six feet of water.

Stanley was killed at the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862.

Maria married a German naval officer, Captain Adolph Mensing. Two of their children, Frederick and Marie Elizabeth, died young and are also buried in the same Lake View cemetery as Benjamin. Mr. and Mrs. Mensing lived in Berlin in 1900. She received a letter in 1901 from President Theodore Roosevelt stating he was not anti-German.

Benjamin is listed on the killed in action panel in the front of Memorial Hall and is buried in New York.

"Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men"

From the book Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men, reprinted in Harper's New Monthly Magazine:

HEROIC DEEDS OF HEROIC MEN.

BY JOHN S. C. ABBOTT.

XVII. - TRUE CHIVALRY. BENJAMIN H. PORTER.

Birth. - Enters Naval School. - The Trip. - Commencement of the Rebellion. — Roanoke Expedition. — Blockading. — Admiral Foote. — Anecdote. - Exploring Charleston Harbor. — Torpedoes. — The Rescue. — Attack on Sumter. — The Capture. — Marched to Columbia. — Imprisonment. — In Irons. — Disappointment and Endurance. — The Release. — Attack upon Sumter. — Death.

ONE may search the records of ancient chivalry in vain for a career more brilliant in heroism than that of the young patriot sailor Benjamin H. Porter. He was the son of James G. Porter and Sarah Grosvener his wife, and was horn at Skeneateles, Onondaga County, New York, on the 10th of July, 1844, the youngest of six sons. When he was four years of age his father moved to Lockport, and there he was educated until his fifteenth year. He was then only remarkable for his cheerful, amiable, and affectionate spirit, which rendered him a universal favorite.

Like all adventurous boys he yearned for a life at sea. A vacancy occurring, in the Congressional district in which he resided, for the United States Naval School at Annapolis, his friends applied to obtain the appointment for him. The Hon. Silas M. Burroughs, sitting member of Congress for that district, took the very proper course of inviting a competitive examination of the young men who were applicants for the position. After an exhaustive and thorough examination of a large class young Porter won the prize. Reaching Annapolis in November, 1859, he was there exposed to another examination ; and though half the class, who were examined with him, were rejected, he was admitted as a cadet, and was immediately placed upon the school-ship Plymouth, which was anchored in the bay.

There were one hundred and twelve cadets in the class which he joined. He remained there until the following June, when his class sailed on their annual cruise to initiate them into the practical duties of seamanship.

On the 1st of July the ship put out to sea. On the 3d they encountered a tremendous gale. The ship sprang a-leak, and all hands were called to the pumps. They, however, reached Fayal, in the Azores, in safety, when the cadets were relieved from their toil and spent a day luxuriously on shore, climbing the mountains and clattering through the vine-clad valleys upon ponies and donkeys. Each of these lilliputian animals had an attendant who clung to his tail and urged him onward by blows and the most unintelligible jargon. Thence they sailed for Cadiz, in Spain. But the cruel quarantine cut them off from every joy. Their chagrin was aggravated by seeing the beautiful pleasure-grounds across the bay crowded with groups of Spanish maidens, graceful as fairies, beneath whose gossamer veils the boys longed to peep.

Making the best of their disappointment again they weighed anchor, and passing by the Rock of Gibraltar and the renowned Pillars of Hercules, they soon ran along the vine-clad hills of Madeira, and steering for the Peak of Teneriffe, enjoyed a few rapturous hours in the Canaries. Again they weighed anchor and reached Chesapeake Bay in September, where they resumed their theoretical studies for the winter on shore.

The storm of the great rebellion was now beginning to rise. Eastern Maryland was terribly agitated. Many of the people embraced the secession cause, and bitter dissensions arose among the officers and cadets of the school, many of whom were from the seceding States. It was feared that the traitors in the school combining with those on the shore might seize the ship, the guns, and the other property of the United States belonging to the Naval School. The officers and cadets who remained loyal gave up all their ordinary pursuits, and stood guard night and day at their battery and on the ship. At length troops arrived to their relief. Then by orders from Washington the pupils, with the effects of the institution, were taken on board the Constitution, and she sailed for New York. Upon her arrival there they were ordered to Newport, Rhode Island, where the school was re-established in a region safe from the assaults of treason. The great civil war was now fairly inaugurated, and the rebels were making their attacks upon the fortresses, arsenals, and important strategic points of the United States with such ferocity that the Government needed the services of every able and patriotic man.

It became necessary for the lads of the naval school to abandon their studies and gird on the sword. The two first classes, and a part of the third, to which young Porter belonged, were ordered to active service as midshipmen. Benjamin, then a boy of sixteen, was assigned to the Roanoke, under Captain Nicholson, and proceeded on blockade duty on the Atlantic coast. It soon became necessary to take the Lieutenants to command new vessels, and this boy performed a Lieutenant's task. He was so faithful, skillful, and successful in these duties as to win the highest approval of his superior officers. The captain, on leaving the ship, voluntarily gave him the following testimonial:

"I can not leave the ship without expressing to you the great satisfaction you have given while on board ship. Your duties have always been performed with alacrity and skill, and I have no hesitancy in recommending you to any one as a very efficient young officer."

Commodore Marston succeeded to the command of the Roanoke. Young Porter immediately won his accustomed place in the new officer's affection and esteem. The steamer unfortunately broke a shaft, and was for some weeks at Hampton Roads engaged in repairs. The Burnside expedition was then fitting out for the waters of the North Carolina Sounds, though no one but the commanding officers knew its destination. Young Porter, chafing under inaction, petitioned for the privilege of accompanying the expedition. The high recommendations he presented from Commodores Marston and Rowan secured his prompt acceptance. And young as he was he was directed to prepare and take command of six ships' launches, each with howitzers, and all carrying a crew of one hundred and fifty men, to accompany the expedition for service in shallow water.

The magnificent squadron entered Hatteras Inlet January 13, 1862. On the 7th of February they commenced their attack upon Roanoke Island. Young Porter gallantly landed his battery and the sailors to man his guns at Ashby's Cove. His pieces were dragged through a morass to a position where he could protect the other troops which had landed, and there he stood guard all of a cold, dark, freezing night, drenched by a northeast storm. At daylight the next morning he advanced with his battery on a line with the skirmishers. Manning the drag ropes, they pressed forward at the double quick until they came in sight of the rebel batteries, when they opened a brisk fire of round shot, grape, and shell, receiving a deadly fire in return.

Here was a lad of but seventeen years of age in the midst of one of the fiercest battles of the war, in charge of a battery of six 12-pound boat howitzers. He had led his men in advance of the lines. His zeal was so intense that he utterly disregarded all peril. When at one gun every man was killed or disabled by the fire from the rebel fort, he stood alone for an hour at that gun loading and firing. For two hours this conflict lasted ; and he remained undaunted at his post until the foe surrendered. His imperial spirit gave him perfect command of his men ; his youthful appearance and almost feminine beauty won their love ; his utter fearlessness commanded their admiration and roused their enthusiasm. He possessed that rare electric power, so singularly developed by Napoleon, which bound his men to him with almost a supernatural affection. It was said that there was not one of his men who would not readily have died for him. The exaltation of his nature may be inferred from the following extract from one of his letters, showing the spirit with which he entered into the battle. It was not the love of fighting ; it was not the love of adventure ; it was not the desire to obtain renown for bravery. It was the highest and holiest impulse which can move a human heart, which thus ennobled him. This youth of seventeen years wrote:

"If I fall remember it is for my country and the noble cause of liberty. For that I came into the country's service ; to fight, and, if necessary, to lay down my life. And I assure you that I am not only glad of the opportunity, but if any thing is to be gained for my country, I will gladly welcome any fate that awaits me."

Admiral Goldsborough, as he took the brave boy's hand after the battle, greeted him with the words: "Young man, you have fairly won your epaulets, and, as sure as there is a God in heaven, you shall have them."

General Burnside, in his report, said: "The skill with which the Dahlgren howitzers were handled by Midshipman Porter is deserving of the highest praise, and I take great pleasure in recommending him to the favorable notice of the Navy Department."

General Foster gave also his tribute of commendation, saying: "I would notice here the gallant conduct of Midshipman Benjamin H. Porter, who commanded the light guns from the ships' launches, and was constantly under fire. He deserves a commission for his admirable conduct on that occasion."

In Admiral Goldsborough's official report he again takes occasion to speak, as follows, of the heroism of this young patriot:

"I deem it but justice to this interesting youth to say, that both Generals Burnside and Foster assured me in conversation, immediately after the battle, that his gallantry was very conspicuous on the occasion. The battery under his command, of six naval howitzers, was placed in the advance, and it was there handled with a degree of skill and daring which not only contributed largely to the success of the day but won the admiration of all who witnessed the display. No other field-pieces were employed by our army in the engagement. Mr. Porter was but seventeen years of age, and, in my belief, no father in the land can, with truth, boast of a nobler youth as a son. I sincerely trust that he may be regarded by the Department as highly worthy of its lasting consideration, and that he may have bestowed on him all that his merits deserve."

The affection which this young man unconsciously drew to himself hy his eminently loving and lovable nature may be inferred from the following letter, which was written to him by Commodore Marston of the Roanoke, and signed by every officer of the ship:

"You have no idea how delighted we all are to hear of your gallant and meritorious conduct in the late action in North Carolina. We all agree that you have justly won your epaulets ; and hope that they, the emblem of devotion, trust, patriotism, and fidelity, may be immediately awarded to you for that unflinching daring, reckless courage, and pure devotion to our noble cause which have distinguished you in the late action."

After the battle of Roanoke he made a short visit to New York. His fame had gone before him. Entirely unconscious that he had attained celebrity, the modest youth took a room at the Metropolitan Hotel. The lamented Admiral Foote, veteran here of the Mississippi, chanced to be there with his family. When young Porter entered the dining-hall he was recognized by the Admiral, who sent a servant with his card to invite him to take a seat with himself and family at his table. He of course accepted the invitation. The marked attention of the Admiral drew all eyes upon him. The general inquiry throughout the crowded hotel was, "Who can he be?" It soon became known that he was the young hero of Roanoke, and he thus became the observed of all observers. This celebrity so much annoyed his modest nature that he quietly removed to the St. Nicholas.

Admiral Paulding, learning that he was in the city, expressed regret that the young man had not called upon him. When this was mentioned to young Porter he replied, "I have no claims upon Admiral Paulding's notice, and certainly did not feel at liberty to intrude myself upon his attention." The Admiral, however, sent a special message for him to call, which he of course obeyed. After an extremely pleasant interview he returned to his mother's apartment. "Why is it," said he, "that every one is so kind to me ? I have done nothing to merit it." She playfully replied, "I do not know, unless it is because you are a good boy and try to do your duty."

His friends in Lockport sent him an elegant sword as a testimonial of their affection and their pride in his achievements. That sword, so nobly won, was his companion in his brief future career, and was placed upon his coffin when he was borne to his burial.

Returning to the navy after this brief respite, he was promoted to Acting Master, and was placed in command of the gun-boat Ellis. It would be difficult to find another instance of one so young intrusted with responsibilities so great — responsibilities which would task the energies of the most mature mind and the most manly frame. With vigilance which never slept he explored the numerous rivers, bays, and inlets of those vast inland seas which wash the coast of North Carolina. In the capture of Fort Macon he took an active part, commanding a floating battery. While engaged in blockade duty in the waters of Pamlico and Albemarle sounds, he one day caught sight of a rebel craft, and in the pursuit gained upon her so rapidly that the rebel captain ran his vessel ashore, and the crew endeavored to escape by the boats. They were, however, all cut off and captured. As they were brought on board the Ellis one of the prisoners was found mortally wounded. Young Porter, to his great surprise, recognized in the bleeding, dying young prisoner one of his classmates at the Naval School, who had embraced the cause of the rebellion. Deeply affected by the incident, he took the captive [[[WILLIAM C. JACKSON, MIDN, CSN]]] to his own room, and nursed him with the utmost tenderness until he died.

In November, 1862, he was ordered to report to Admiral Du Pont, at Port Royal. Here he was again for a few months employed in the blockade service, on the ship Canandaigua. He acquitted himself so acceptably, and displayed such energy and vigilance, that in July, 1863, he was selected by the Admiral to perform the exceedingly difficult and perilous duty of exploring Charleston harbor, under the guns of all its innumerable batteries and its fleet of patrol steamers, to search out its obstructions. This was a duty which could only be performed in dark and often stormy nights, when the adventurous party, in their open boats, were tossed by the waves and drenched by the rain. That one so young should have been selected for a duty so arduous, so full of peril, and requiring such combined energies both of daring and of prudence, is one of the highest possible compliments which could be paid to the reputation of this young man.

For twenty-four successive nights he was engaged in this enterprise. During every moment of this time he was exposed to the most imminent danger from the torpedoes, picketboats, gun-boats, forts, and batteries of the enemy. So deeply did he feel his responsibility, and with such entireness of consecration did he devote himself to the work, that while the labor lasted he lost a pound of flesh each day.

Every night he found rebel picket-boats on the watch, and was frequently chased by them. On the occasion of a general night bombardment of Wagner, which attracted the attention of all in that direction, he slipped around in his boat between Sumter and Moultrie, and for three hours was uninterrupted in his explorations. He stood in the bow of the boat, in darkness which was only illumined by the flash of the guns, with his boat-hook feeling for and dodging torpedoes. At length he came across a buoy. Not knowing but that it was attached to a torpedo, he carefully approached and threw a rope over it, and then, backing some distance, he pulled upon it. As it proved to be harmless he again approached, and feeling with his boat-hook found it supported a large chain. Following the chain under water he soon came to other buoys and timbers, stretching across the channel. Following these up he found the opening for blockade-runners. Carefully making observations, to be sure of finding it again, he returned to the fleet and reported to the Admiral, offering to pilot the Monitors through.

One night twelve large yawl-boats were sent out from our fleet, each containing about twenty-five men and a heavy boat-howitzer, to cruise between Sumter and Cumming's Point, to prevent any rebel communications between them. It was a dark night, and the utmost vigilance was necessary, since the rebels had picket-boats, driven very fast by steam, constantly patroling the harbor. Two of our Monitors had approached the rebel forts as near as they could in safety, that they might assist the yawl-boats in case of need. Ensign Porter, in command of one or two small boats, which were less exposed to observation, and which could run in the shoal water near the shore, where the rebel gun-boats could not pursue them, and in the gloom of night could not see them, had crept up beneath the guns of Sumter and almost to the wharves of Charleston. With muffled oars and a strong pull he came rushing back to one of the Monitors with the tidings that a rebel steamer was under way and was coming down the harbor.

A larger boat was at once pushed ahead on a scout. It was so dark that nothing could be seen at a distance of a hundred feet. It was a windy night, and the dashing of the surge and the breaking of the waves prevented any ordinary noise from being heard. Suddenly a rebel steamer emerged from the darkness, rushing down directly upon the scout-boat, which had been sent from the Wabash. The rebel steamer caught sight of the boat, fired a gun into her, and dashing on, struck the boat on the bow, breaking her to pieces. The men leaped into the water, and as the steamer swept by volleys of musketry were fired upon them while struggling in the waves. Ensign Porter, hearing the report of the howitzer, the firing of the musketry, and the cry of the drowning, utterly regardless of his own danger, ordered his men to bend to their oars to rescue the crew. There is something truly sublime in the vision of that fragile boy of eighteen, in that dark and stormy night, with no eye to see him but the eye of his God, with no impulse to urge him but his own noble soul, rushing into the very jaws of destruction and death to save his drowning comrades. In a moment he was in the midst of them. Eight he dragged from the water into his boat. The steamer had actually passed over them. It now turned to complete its work, and yet young Porter, with apparently as much coolness as if in his father's parlor, flashed the light of his dark lantern all around over the waves to ascertain if any more drowning men could be discovered ; though he knew full well that those gleams would but guide the on-rushing rebel steamer down upon him.

The flash of his lantern -revealed to him the steamer heading directly for his boat. By this time there was a general alarm in the Union fleet. The light of Porter's lamp had revealed the rebel gun-boat to the Catskill, and she opened upon her with her ponderous guns. The gun-boat could not for a moment cope with such an antagonist, and putting on all steam she fled back into the harbor, while at the same moment young Porter, with the rescued crew, plunged into the gloom of the storm and of the night, and returned to the fleet in safety.

This is but a specimen of the services our hero rendered in these twenty-four nights of unexampled toil. He would sometimes return to the fleet so exhausted that his crew would have to lift him from his boat and lay him like a child in his berth, administering stimulants to restore him.

This was a period of intense activity in the harbor. There were daily bombardments, and earth and ocean seemed to shake beneath the tempest of war.

Ensign Porter, after an hour or two of sleep, would be again found on the gun-deck, commanding his section of guns in action, stripped to shirt and trowsers, black with smoke and powder, sighting every gun. His spirits were always elastic and joyous ; never a complaining word or a confession of fatigue or a downcast countenance. The bombardment from our fleet and land batteries had crumbled the walls of Sumter into ruins. Still those ruins afforded impregnable protection to the rebel garrison, who in casemates of rock manned its guns. Admiral Dahlgren deemed it advisable, before attempting to penetrate the harbor with his ships, to get full possession of the fort, which seemed to be only a mass of crumbling ruins. He organized an expedition of boats to storm the fortress in a night attack. It was a very perilous enterprise, for the garrison could open upon the assailants with grape and canister, and all the surrounding rebel forts could concentrate upon them the most deadly fire.

Though the result of the expedition could not but be doubtful, the importance of the enterprise was sufficient to warrant the hazard. Ensign Porter, ever eager to lead where the blows fell thickest and fastest, implored permission to join the undertaking. Commodore Rowan, aware of the priceless value of such a life, very reluctantly gave his consent. Thirty boats, carrying seven hundred men, were collected ; and on the night of September 7, 1863, the attempt was made. The rebels, with their glasses, could see the boats collected from the fleet, and made every preparation to meet the assault. They sent down from Charleston a reinforcement of three hundred men, with every needful provision to repel the assault ; they also brought some gun-boats into position, and had all the adjoining forts in readiness to overwhelm, by a concentrated fire, the assailing party with swift destruction.

In the darkness of the night stealthily the boats approached Fort Sumter. Suddenly there burst upon them such a storm of iron and of lead from the garrison, the gun-boats, and the batteries as no mortal valor could withstand. This tornado of war swept every boat back but three. One of these three was commanded by Benjamin H. Porter. These three boats reached the debris of the fort. A hundred men sprang from them upon the broken mound of brick and stone, with the deafening thunder of artillery filling the air, and with round shot, grape-shot, and hand-grenades flying in all directions around them. The wounded, the dead, and trails of blood marked their path as they ascended the rugged acclivity a distance of forty feet. Here they unexpectedly encountered a perpendicular wall 16 feet high, with its top crowded with rebel sharp-shooters. They threw down handgrenades which, bursting in the boats, blew them to pieces. These grenades also fell with fearful destruction into the disordered ranks of the assailants. At the same time fire-balls were thrown down which lighted up the whole scene as bright as day, enabling the garrison to take unerring aim at the little handful of men struggling at such fearful odds. Our brave tars sheltered themselves as well as possible behind the debris of the battered walls, and, refusing to surrender, continued the fight for two hours, hoping the boats would return or the fleet come up to their assistance. But no help could be sent them, and after the loss of many men the remnant were forced to surrender and were marched into the fort as captives.

The commander could not but admire the gallantry they had displayed, and received them with much courtesy. "Gentlemen," said he, to the officers, "you are unexpected guests. But I will entertain you to the best of my ability."

The next day they were allowed to send to the fleet for clothing and money, and were then dispatched by steamer to Charleston. As they landed upon the wharf, and were marched through the streets to the jail, the whole population of the city crowded around them with exultation. They were soon after removed for safe keeping to Columbia, South Carolina, and there this heroic young man and his brave comrades were subjected by their barbarous foe not to the treatment of prisoners of war, but they were shut up in close confinement like felons in a jail. For fourteen months Benjamin Porter endured these woes, with a resolution of spirit which never for one moment flagged. At first he was sanguine in the hope that an exchange would soon be effected ; but as the dreary months of imprisonment rolled on and all those hopes died away plans of escape began to be meditated. With long and perilous toil they contrived to dig a tunnel under the hearth to the outside wall, ingeniously concealing their operations from their jailer. They had so far succeeded in this enterprise that the work of one more day would have carried them so far that, in a dark night, they could have broken through outside of their prison walls. Though they would then have been in the very heart of rebeldom, they doubted not that their sagacity and energy would enable them to elude their foes and escape to a land of freedom. When one of his companions suggested the apparent hopelessness, even if he escaped from the prison, of ever reaching from such a distance the Union lines, he replied:

"No matter ; the enjoyment of a sense of freedom and of Heaven's pure air for one day, or one hour, is sufficient to warrant all the toil and all the exposure to recapture or death!"

Just at this time their plan was discovered — betrayed, as was believed, by a traitor in the building. Bitter indeed, almost heart and hope crushing, was their disappointment. It is said that sorrows go in troops. Porter had now been three months in captivity when a new and very terrible calamity befell him. The rebel Government, as an act of reprisal for the imprisonment as pirates of some rebel privateers, ordered two officers at Columbia — Lieutenant Williams and Ensign Porter — to be put into close confinement in irons, as hostages. By some misunderstanding the rebel privateersmen had been thus treated. The matter, however, was promptly brought to the notice of our Government, and the assumed pirates were released from irons. But it so happened that at this time, for several weeks, there was a rupture of all communication between the two hostile parties. Consequently these two officers (Lieutenant Williams and Ensign Porter) remained in irons, in utter solitude and in close confinement, in a cold and gloomy cell, without fire, bed, or chair, from early in December to the 15th of March. The clanking of their chains at every move they made could be heard distinctly by their comrades in the adjoining room. In the following terms this brave-hearted, uncomplaining boy — cold, hungry, and fettered — wrote to his father:

"Lieutenant E. P. Williams and myself are in irons and close confinement, held as hostages for Acting Masters Braile and McGuire, of the Southern navy, now, as I am informed, confined at Fort McHenry to be tried as pirates. I wish you would see what you can do for me ; for although we are as comfortable as can be under the circumstances, still we are far from being comfortable."

He knew well what would be the throbbings of a father's anxious heart and of a mother's tender love did they know the sufferings which their child was enduring. He would therefore conceal his anguish, and only let them know just so much as was necessary to guide to efforts for his relief. It was not, however, until March, 1864, that the chains were stricken from his limbs, and he was cheered by the tidings that he was to be removed to Richmond, there to be exchanged. But a new disappointment fell upon him. The advance of General Butler up the James River, and the opening of Grant's magnificent and final campaign before Richmond, broke off communications. A long and tedious summer of continued imprisonment ensued, wearing much upon the health and fortitude of all the prisoners. But it is their united testimony that through all these lingering months of suffering not a complaining word escaped the lips of Ensign Porter. His generous sympathy, his happy, hopeful spirit so cheered the sinking hearts of his comrades that they regarded him almost as an angel of consolation.

It so happened that there was a young lady resident in Columbia who had known Ensign Porter in his favored home of competence and refinement in the North. Learning accidentally of his incarceration, she applied for permission to see him, but was peremptorily refused. She, however, contrived to open a correspondence with him, occasionally sent him some comforts, and at last, by her generous persistence, induced the friends in Columbia of a rebel officer who was confined on Johnson's Island, in Lake Erie, to pay Ensign Porter $300, upon his promise that his friends at the North should remit the equivalent to their relative. She was enabled to make such a representation of the ability and honor of the family, that the verbal promise of the young captive was deemed ample security. This money contributed much to the comfort not only of Ensign Porter but to that also of his companions. He was now able to write home ; but the only complaint to be found in his letters was "that, at his age, he could not afford to lose so much time while there was so much active service to be done."

In the winter of 1S63 General Burnside arrested a rebel officer found recruiting in our lines in Kentucky. He was tried by courtmartial and executed. Soon after, the rebels found a Captain Harris, of East Tennessee, engaged in the same business within lines which they claimed as theirs. Pending reference to Richmond for confirmation of the sentence of death which a court-martial had pronounced upon him, he was confined in irons in a room opening from one in which the naval officers of the Sumter expedition were confined. He had been there several months when these officers arrived. Ensign Porter, on being relieved from irons and returned to his old room, succeeded with his jack-knife in removing or springing the lock of the door of Captain Harris's room. Then, after much effort, he taught him how to slip his irons off and on again. This was to him an immense relief, as he would slip them on only when the jailer was about to enter the room. When Ensign Porter and his associate officers came North they left Captain Harris still in his room, liable any day to be led out to be hung ; and there he remained, with a brave and manly heart, this terrible doom ever impending over him, until the approach of General Sherman's army in the spring of 1865.

In the confusion of these tumultuous scenes, when the sweep of Sherman's columns was spreading dismay in all directions, the jail took fire in the night and was entirely consumed. In the morning Captain Harris's shackles were found among the glowing embers, and it was supposed that he had miserably perished in the flames. But the brave Captain, in the confusion of the fire, and aided by the dismay which then agitated all Southern hearts, had quietly dropped his shackles, walked forth into the streets, and made a straight path for his feet to our army lines at Wilmington. Here he met with warmest congratulations some of those friends who had so sadly left him at Columbia a prisoner in chains awaiting the scaffold.

In October, 1864, an arrangement was effected for the exchange of all the naval officers and men captured at Fort Sumter. Mr. Porter emptied his pockets of all his money, and gave all his spare clothes and other effects to his friend Colonel Payne, a distinguished officer of the One Hundredth New York Volunteers, who had shared his imprisonment, but who was not permitted to share his release.*

* I can not refrain here from paying a brief tribute of respect and affection to Colonel L. S. Payne, who had done so much and has suffered so much for his country. While Ensign Porter was reconnoitring the fortifications and positions of the enemy in Charleston harbor Colonel Payne was engaged in the same service in the labyrinth of creeks south of Sumter. These two officers were summoned to meet on board Admiral Dahlgren's ship for concerted action. Unfortunately the night before the appointed meeting Colonel Payne was shot through the neck and captured. They soon met as captives in a rebel prison, and for weary months suffered together, each cheering the other. For some time before Ensign Porter's release they were lodged in the same room, and a very strong affection sprung up between them. "After Mr. Porter's release from irons," writes Colonel Payne, "he managed to get some old naval works on navigation, and some mathematical books, and a work on geometry. To these he devoted most of his attention in study, often saying that he intended to be the first in his class, on examination, when exchanged."

With a buoyant heart young Porter found his steps directed toward his home. On arriving at Richmond he was placed in Libby Prison, and after ten days of vexatious delay was finally sent to our lines. Taking passage for Washington he, with some others, arrived there the next day and reported to the Navy Department. Porter proceeded that night to New York, where he had a happy reunion with those dear friends who loved him so tenderly, who cherished him so proudly, and whose hearts had bled with such anguish in sympathy with his sufferings and his perils. His two years of toilsome service, of gloomy imprisonment of hard fare, had left their traces on his once beaming and happy face. His frame was emaciate, his cheeks sunken, and his countenance bore a premature expression of care and sadness. A few months had done the work of years. He was no longer the light-hearted, joyous youth who had so buoyantly left his happy home but a few months before, but the mature man, war-worn and pressed down by as weighty responsibilities as can ever rest upon a human heart.

The reaction from the gloom of the prison to the glowing affections and comforts and endearments which now clustered around him were so great that for many nights he was tortured with restlessness and the most hideous dreams. He was starving ; he was escaping from prison ; he was recaptured ; he was dragged back to dungeons and chains ; he toiled in vain to unclasp his irons and they ate into the bone. The suffering of these nights was positive and extreme. Gradually, however, as parental love so tenderly encircled him these impressions wore away, and his countenance resumed its former expression of beauty and of joyousness.

Just before his imprisonment he had been ordered to proceed to Newport to be examined for promotion. It was now necessary that this should be attended to. A special board of examiners was convened at Washington, with his early friend Admiral Goldsborough at its head. He passed an excellent examination, and his rank of Lieutenant was dated back to the preceding February, when he was but nineteen. This is probably the only instance of that rank being attained in our navy at so early an age.

Ensign Porter was not yet exchanged, but was liberated on his parole. He, however, reported to the Secretary of the Navy in his new rank as Lieutenant, stating that he was ready and anxious for active service as soon as his exchange could be effected. Since he was fifteen years of age, excepting the time of his imprisonment, and while at the Naval School, he had spent less than sixty days on shore. While waiting for this release from his parole he had leave of absence, and visited his childhood's home in Western New York. In the greetings with which he was received by his neighbors, friends, and old school-mates, he seemed entirely unconscious that he had done any thing worthy of remark, while he was loud in praise of the exploits of his brother officers.

He had been at home but two days when a telegram from the Department announced his exchange, and summoned him to report immediately to Admiral Porter at Hampton Roads. He had hoped to have spent Christmas with his friends, which would have been the first he had enjoyed at home for five years. But ere that day came he was with the fleet thundering at the walls of Fort Fisher. With all possible speed he hastened for Hampton Roads. There he found that the squadron had already sailed for Beaufort, North Carolina. Embarking on board a transport he reached the fleet and reported to the Admiral. He was warmly received, and immediately placed in command of the flag-ship, the Malvern. The following anecdote is related in reference to his arrival at the fleet: One of the most distinguished Captains, having heard that Lieutenant Porter had reached the squadron, ordered his boat, and, proceeding to the flag-ship, asked for an audience with the Admiral.

"I understand," he said, "that Lieutenant Porter has arrived."

"Yes, Sir," was the reply of the Admiral.

"Well, I want him."

"What do you want him for?"

"Why, I am short of officers, and I know him, and I have written to the Department for him."

"Do you want him very much?" the Admiral responded.

"Yes, Sir."

"Will it make you sick if you don't have him?"

"I don't know but that it will."

"Well, you can't have him. He commands this ship, Sir."

Lieutenant Porter passed through the first battle of Fort Fisher safely. In planning the second attack, as the fort had been largely reinforced and strengthened, the Admiral deemed it necessary, in addition to the land troops, to send on shore all the force which could be spared from the ships. About eighteen hundred sailors and marines were thus landed. Lieutenant Porter, carrying the Admiral's flag, claimed the right to lead the assaulting column. Just before the conflict he wrote to his mother:

"We are now off New Inlet once more, for the purpose of taking Fort Fisher ; and this time, by God's blessing, we mean to do it. We have General Terry in command, and he is young and ambitious. I hope he will make his men fight. It is 4 o'clock in the morning, and we are moving in for the attack. We will strike a telling blow for Columbia to-day. America expects every man to do his duty, and our gallant tars never flinch."

Another letter which he wrote to a young friend and companion in arms reveals the inner man — the ardor of his affections, the nobleness and the purity of his aspirations, and that lofty faith which allies man to the angel. His young friend had recently become a Christian, and the letter from which we quote is in response to one which he had just received from that friend announcing this fact:

"I was made very happy to-day by the receipt of your letter of the 3d instant. And, my dear friend, although I can not say that I am a Christian, I was made happier than I ever was in my life before by knowing that you, the dearest friend on earth to me, had at last 'tacked ship' and become a Christian. Your letter has made me stop and review my past life, and I assure you that my past wickedness really frightens me. It seems as if I had gone too far to hope for forgiveness. It seems as though God would never receive one so wicked as myself. But as Christ died to save us all I shall hope that, by trying to be good the rest of my life, his blood will wash out my many sins, and that at last I may stand at your side, one of our Heavenly Father's chosen. It will be a hard road to travel for a while, but I am determined to give up all my old wicked habits and try to the utmost to be a true Christian.

"As I said before, I can not feel that I am a Christian, although I know that Christ died to save me. But if God will keep me I will try and be one ; and I know that I can succeed if I try, for our Heavenly Father has promised to listen to ail who ask him with their whole hearts. How could you imagine that I could love you the less because you are a Christian? No, no, Adams, I love you more, if such a thing be possible, than I ever did before. And now I beg you to pray for me, and ask God to give me a new heart and teach me to pray. I shall pray for you every night.

"I am going ashore to lead my men to the charge on Fort Fisher ; and if God will keep me from harm and bring me out of the fight in safety I will try and obtain a ten days' furlough, and then, my friend, I will see you. I have been in command of the flagship several weeks, and am very pleasantly situated. I expect that we shall have a very hard tight, and as I am going to assault the fort I run a good chance of losing the number of my mess. But if I do, my ever dear friend, you must remember that I love you with my whole heart, and I know that you will think of me sometimes. I shall write you again from New Inlet, and give you an account of the tight. Until then I beg of you to think of me and pray for me, and I will do the same for you."

The following extract from a letter written, after the death of Lieutenant Porter, by the friend to whom the above letter" was addressed will be read with interest. It was written to the father of the deceased, under date of April 3, 1865:

"I visited the Malvern a few days since and went into poor Ben's cabin — a cozy, comfortable little place — and I wished I could have been alone for a little time. It was a greater trial than I had anticipated, and every thing seemed to bear a reference to Ben.

"Since I sailed I have been through the places where we were together years ago, or in which he had been since we parted. I have been daily and hourly brought in contact with persons and objects which have brought him to my mind, and every time his memory is dearer and purer than before. It is now a part of my very self. Every thing I undertake I wonder if that would have been his way of doing it ; and his example is the model I try to follow.

"I miss him in my duties and in my plans, and every day his absence seems more and more unbearable. And every day I feel a greater and prouder satisfaction in the knowledge that so noble and gallant a hero as Ben called himself my best-beloved friend ; and I thank my Heavenly Father daily for it, and for the happy promise of Ben's eternal rest in His arms."

The terrible hour for the assault came. Young Porter, bearing the Admiral's flag, claimed the post of honor in leading the headmost column with the Malvern men. As he left the ship, with the flag in his hand, he said, "Admiral, this shall be the first flag on the fort." Admiral Porter's own son, but seventeen years of age, went by his side. But Lieutenant Porter's hour had come. Accompanied by two of his best friends, and two of the most heroic young men the war has developed — Lieutenants W. B. Cushing and S. W. Preston — he took his place at the head of the column. Under a heavy fire from the enemy's guns, which exposed them to instant death, they advanced, about 2 o'clock in the afternoon, to within four hundred yards of the immense works of the foe. They then threw themselves upon the sand, and remained there quietly talking while the battle raged with deafening roar, and thousands of shells were hurtled through the air over their heads, as the majestic fleet and equally majestic fort exchanged bombardments. At last the signal was given to charge. They sprang to their feet. The only survivor of the three young men, Lieutenant W. B. Cushing, the hero of the Albemarle capture, whose fame can never die, thus describes the scene which ensued:

"Ben looked grave and determined, and I remember being much impressed by his supremely noble bearing. In a moment we were under a terrific tire, and the men commenced to get confused. It needed all the pluck and daring that man can have to lead and give confidence to the sailors in charging up that bare and level beach. Ben threw himself to the front, flag in hand, and the charge went on. We were all three in uniform, perhaps rashly, but it has ever been the pride of naval officers to wear, amidst the smoke of battle, the same lace that denotes their rank when enjoying the pleasures of society.

"At the palisade, by the ditch that surrounds the fort, Ben fell, shot through the breast. His last words were, 'Carry me down to the beach.' Four of the Malvern's and Monticello's men raised him and tried to comply. Two were killed. He waved the others aside with a last motion, and died, with as sweet a smile as I could paint with words. I doubt not that some world met his dying eyes where spirits so pure, so noble, so brave as his meet with an eternal and great reward. The blood-stained fortress where he fell will stand forever a monument of tender and sorrowful recollections to us all. It would be idle to measure a brother officer's regards by a parent's love ; but he carries the respect and affection of all to the grave, and has left a navy of mourners."

His friend and companion Lieutenant S. W. Preston fell almost at the same moment, and together the spirits of these two noble young men took their flight to their celestial home, where, we trust, clustering angels gathered to greet them. Fleet-Captain K. R. Breese, in his Report to the Admiral, pays the following beautiful tribute to the memory of these two young men, who so cheerfully sacrificed their lives for their country:

"Lieutenant S. W. Preston, after accomplishing most splendidly the work assigned to him by you, which was both dangerous and laborious, under constant tire, came to me, as my aid, for orders. Showing no flagging of spirit or of body, and returning from the rear, where he had been sent, he fell, among the foremost at the front, as he had lived, the embodiment of a United States naval officer.

"Lieutenant Porter, conspicuous by his figure and uniform, as well as by his great gallantly, claimed the right to lead the headmost column with the Malvern men he had taken with him, carrying your flag, and he fell at its very head. Two more noble spirits the world never saw ; nor had the navy ever two more intrepid men. Young, talented, and handsome, the bravest of the brave, pure in their lives — surely their names deserve something more than a passing mention, and are worthy to be handed down to posterity with the greatest and best of naval heroes."

There is heart-touching pathos in the following letter of condolence from Admiral Porter to the bereaved mother:

"Your gallant son was my beau-ideal of an officer. His heart was filled with gallantry and love of country. It must be a dreadful blow to lose such a son. It was a dreadful blow to me to lose such an officer. My associations with my officers are not those of a commander. We are like comrades, and form fond attachments to each other. When they fall I feel as if I had lost one of my own family. Your son was captain of my flag-ship, and a favorite with me and all who knew him.

"He was brave to a fault. I shall never forget the day he left the ship, with my flag in his hand, saying, 'Admiral, this shall be the first flag on the fort.' My own son, a lad of seventeen, went by his side, and was with him when he fell, with my flag in his hand, trying to reach the enemy's ramparts, from whence the murderous wretches were firing thousands of muskets into our brave fellows.

"That was a wretched night for me. Your son was reported killed, and mine, last seen at his side, was missing till late in the night. I could imagine his father's anguish, and I could imagine yours. I have no consolation to give you, unless to console you with the certainty of meeting in a better world than this. I have gone through a great deal in this war. For four years I have been but one month with my family. I have seen my official family cut down one after another, and my heart is so sad that I feel as if I could never smile again.

"Among all the young men who have been on my staff no one had my entire confidence more than your lost son— lost only for a time. You will find "him again where all is peace and joy. I would like to drink of the waters of Lethe and forget the last four years."

It is a remarkable fact that the best of men feel their sins far more deeply than do the worst. Young Porter felt that he was a "great sinner" in the sight of God. And yet so unblemished were his morals, and there was such maidenly purity in his character, that, to his friends, he appeared without a stain. When we see such a one shedding tears of penitence, breathing prayers for pardon, hungering for a more holy life, pleading for renewal by the Spirit of God, and casting himself upon the merits of the great atonement, and when we remember that he cheerfully sacrificed his life for the most sacred cause in which men ever drew the sword, it is not without reason that we feel assured that angels bore him on their wings to his celestial home.

The morning after the battle Admiral Porter dispatched a steamer for Norfolk with the bodies of Lieutenants Porter and Preston escorted by Lieutenant Saunders, a friend of the deceased. Thence the body of Lieutenant Porter, in a metallic case, was forwarded to his friends in New York by express. Commodore Paulding was anxious to honor the memory of the departed by a public funeral, and General Burnside expressed a wish that the land troops might join in the procession. But the grief of his friends was so deep that they had no heart for the public display, and they chose to retire with the remains of their loved one to his birthplace that he might sleep by the side of his brother and sister.

And as the precious body sank into the grave the anguish of both father and mother found solace in gratitude that God had given them the remains to bury ; for another son of this patriot family, the peer of Benjamin in all those traits which ennoble man, had previously fallen in the second battle of Bull Run. Two journeys the heart-stricken father made to that field, where treason had so cruelly robbed him of his boy, and twice he returned to his desolated home, having searched the graves in vain to find the body of his son. It would be a comfort to weeping friends could the remains of these noble brothers slumber side by side here below. But it is a greater comfort to feel assured that their spirits have met in heaven ; that there they are now, brother angels, hand clasping hand and heart beating responsive to heart in joys which shall never fade away.

Near the banks of one of the most beautiful lakes which gem the Empire State the remains of Benjamin H. Porter now repose, awaiting the resurrection summons. He sleeps with many of his loved kindred around him. And whoever drops a tear over his grave may say: "Benjamin H. Porter merits these tears, for he was a cherished son, a noble brother, a brilliant officer, a warm-hearted friend, and a humble Christian."

Career

From The Sea Eagle: The Civil War Memoir of LCdr. William B. Cushing, U.S.N.:

A friend of Cushing's from the Naval Academy, Porter had seen much active service, including capture and imprisonment in an 1863 raid on Fort Sumter. He relieved Cushing as commander of the flagship Malvern when Cushing returned to his old ship, the Monticello. Porter was killed leading his men during the naval land assault on Fort Fisher January 15, 1865. Cushing was nearby, as was Porter's best friend, Lieutenant Samuel Preston, who was also killed in the assault.

From the Naval History and Heritage Command:

Acting Midshipman, 1 December, 1859. Ensign, 8 November, 1862. Lieutenant, 22 February, 1864. Killed in attack upon Fort Fisher, 15 January, 1865.

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together… or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

January 1860

September 1861

September 1862

January 1863

January 1864

January 1865

Related Articles

Samuel Preston '62 was also lost in this assault; he was Flag Lieutenant to Admiral Porter, who was embarked on Malvern.